Support Lucid News

Essential Psychedelic Journalism

“Demons and Christians” was first published by author Erik Davis on his Substack Burning Shore.

Come all you faithless, you metalheads and cultural Marxists, you climate scientists and abortion docs, you Buddhists and Muslims and devotees of many-armed goddesses, and of course you Jews too, can’t forget the OGs, the queers and pinkos right alongside ya, yes and you UFO buffs and feminist podcasters and porn stars, you Open Society wonks, YA fantasy writers, and DEI managers, you trans boys and girls, and transhumanists too, wireheads and Burners and AI overlords, you Hollywood stars and yoga teachers and R&B pop stars flashing pyramid signs, not to mention you actual Satanists and Freemasons and witches and heathens, and how could we skip you critical race studies adjuncts and Procter & Gamble execs, and of course you Darwinists and antifa punks and gay priests, all of you now, all of us, let us take a moment here amidst our variant identities and discords to acknowledge our shared humanity — or rather the shared subhumanity we assume before the jabbing fingers of literally millions of rightwing Christians in American, who have identified us all, at least at one time or another, as, if not directly possessed by devils and demonic forces, then at the very least in thrall to them, whether we know it or not.

As we near War between the States levels of polarization in this God-haunted land, it is important to remember that demonization does not simply refer to the extreme othering of one’s political, ethnic, or cultural opponents. It also means the literal identification of evil supernatural forces at foot, either indirectly, by way of lies and deceit, or through overt domination and puppet mastery. Consider the apt word “Manichean,” which commentators on both the left and right increasingly use to describe today’s splintering discursive battles. The term comes from the third century prophet Mani, who wowed the world of late Antiquity with the old Zoroastrian vision of the cosmos as a perpetual battleground between irreconcilable forces of light and darkness. And while Christianity eventually beat out this one-time rival with a technically less dualist theology, the Manichean rumble in the jungle is always lurking just below the surface of the Christian imagination.

Some contemporary Christians call it “spiritual warfare.” Such battles sometimes take place on an individual level, like the office or the local elementary school, but they are also waged on the wider stage of cultural institutions, public discourse, and politics. Demonizing on that scale can lend an apocalyptic urgency to collective action, a feverish dreamlike ferocity. It also makes dehumanizing your enemies easy — their rights and privileges, even their “common decency” as human beings, can be ignored because they, or rather we, are simply sock-puppets of the real Enemy, who can and must be hated without a shred of countervailing empathy. We can be pitied, but still hated. Indeed, I suspect that the dynamics of spiritual warfare provide much of the secret sauce for Trump and MAGA’s surrealpolitik program of outrageous exaggeration, conspiratorial lies, and feverish contempt. Start tussling with demons, and everything gets turned up to 11.

Shit gets infectious too. As the mediation of consensus reality shatters into a funhouse mirror horror show, worldviews formally pitched too far from a basically rational pragmatism suddenly gain traction and explanatory power. Paranoia earns supernatural warrant, and balloons as the Armageddon horizon approaches. Despite the terrible irony of Peter Thiel’s own personal emulation of Antichrist behavior, his End Times warnings of late have been savvily timed. The Great Unraveling is upon us, and Christianity is back in black. This is not Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Jesus, marching with the downtrodden hand in hand, but the dude with a sword, ripped AI muscles, and a Crusader cross. Church attendance is rising after decades of decline, even though a lot of MAGA Christians don’t bother much anymore. Gen Z dudes are going Orthobro, prophecy is booming, and all manner of spiritual warriors are girding their loins and loading their AR-15s. Everyone senses the collapse of the secular liberal order, and the loss of all certainties but apocalyptic ones.

Take Tucker Carlson, a secular blowhard who made a religious turn a year ago when he started talking about scripture and the demon who attacked him in bed. Recently this former Deadhead dropped a doozy: “The Occult, Kabbalah, the Antichrist’s Newest Manifestation, and How to Avoid the Mark of the Beast,” a podcast conversation with a callow Hollywood insider named Conrad Flynn. Flynn covers a lot of familiar Techgnosis territory — Marshall McLuhan, Jack Parsons, John Lilly, William Burroughs, AI occultism, transhumanism, Antichrist — so I had planned to take it all in and deconstruct the thing so that you didn’t have to. Reading the tea leaves and all.

But I’m sorry, I just couldn’t bring myself to add one more pair of ears to a shitstream currently clocking in at 2.6 million views on YouTube alone. Even just scanning the transcript made me feel woozy and sad. Flynn is one of those fools who knows just enough to get himself into trouble as he sloppily red-threads his way toward some revelation about occult elites conjuring a demonic AI Golem. Despite some good thoughts on AI, and his sometimes arcane knowledge (Grant’s Nightside of Eden, etc.), his vision adds up to little more than the sort of “Mark of the Beast” malarkey that illustrates the podcast — a trope that goes back to the early 1970s, when Flynn’s psychedelic Mom first went Christian. Start tracking demons, and your critical IQ heads south.

Don’t get me wrong. I kind of enjoy this stuff, and not just because Flynn’s mode of slapdash but ominous hermeneutics is itself a familiar part of occult thinking, like a crazy uncle who can still tell good stories. Strong conspiracies often function as twisted allegories of real conditions, and this very much applies to the sorcerous discourse of occult technologies. I was particularly taken with Flynn’s resurrection of John Lilly’s ketamine visions of a malevolent Solid State Intelligence taking over the universe — a 70s High Weirdness baddie now making a come-back through AI prompts and the myriad of k-holes that tunnel their way through Silicon Valley.

There’s another reason to track this sort of stuff, and even encourage it: the half-assed hope that techlord demonizing widens the fissure in MAGA between populist Christian paranoids and the Promethean transhumanists represented by Musk and other proto-cyborg superbrights. Tucker is one of the rightwing pundits leading this charge, along with Steve Bannon and Candace Owens, who recently announced that she believes that Musk, Thiel, and Sam Altman are “hybrids” rather than humans. “It’s something in the eyes,” she said, and I totally agree. “I’m like, I don’t know if I stabbed you if you bleed, you know? I’m not going to stab them, but I don’t know if they bleed all the way. I think a battery would fall out. You know what I mean? And I just get that sense. I’ve always known it was demonic.”

But maybe it’s just all those drugs that Musk and his battery-operated cronies are consuming. That said, the psychedelics that Flynn and Tucker inevitably discuss are not demonized as such. While the weirdness of ketamine and DMT are invoked, psychedelics are not framed as a demonic transhumanist plot to destroy Christian civilization, or to channel the legions of hell, or to confuse and conceive the minds of the young or the spiritually hungry. Instead, psychedelics are treated as truth-tellers, offering proof that there no shit is a spiritual world as real as this one, and that this other realm is inhabited by supernatural agents, including demons but also, just maybe, the angels of the Lord, if not Him Hisself.

Indeed one curious feature of today’s rightwing Christian demon discourse is the relative absence of anathemas proclaimed against psychedelics. Perhaps there is something here for us. As both commentators and activists have noted, the embrace of psychedelic healing has become one of the very few bipartisan issues in our schizoid land. This fragile consensus has been constructed most visibly by MAPS’ Rick Doblin, who for years has cultivated military interest in MDMA therapy both at home and abroad. But the consensus also represents the organic demand from conservatives and particularly veterans — many of whom are serious Christians, natch — to get in on those potent healing powers, including far heavier ones than molly.

Given the horrible rates of suicide and PTSD among soldiers, groups like Heroic Hearts, Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions, and the Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition are demanding widespread access to psychedelic therapy. Earlier this year, the Texas governor Greg Abbott, no friend of plant medicine hippies, shepherded a bill supporting research into ibogaine, a bitter root used by decidedly pagan West African wizards that has become the clear market favorite for messed up vets turning to the underground or overseas providers. The official military deployment of psychedelic healing is hardly without controversy. Those of us who grew up associating Ecstasy with PLUR quaver at the prospect of active-duty soldiers getting their heads straight with MDMA before returning to the killing fields, a therapeutic protocol that is currently being studied in a DOD-funded clinical trial. Nonetheless, this military psychedelic turn has created a significant wobble in American Christianity’s demonization force field.

Let’s pause and consider how extraordinary this is. For the last year or so, I have been studying the history of the Jesus Freaks, those hippies who found the Lord in droves in the early 1970s, many through psychedelic experiences both harrowing and divine. In those fractured days, when political polarization was also running high, both conservative Christians and the longhaired converts viewed LSD and other psychedelics as instruments of satanic deception on a par with Tarot cards, yogic samadhis, and witchcraft orgies. There are also deep historical reasons for demonizing psychedelics this way. Indeed, the rhetoric of Nixon’s Drug War that was emerging at the time, as well as Harry Anslinger’s earlier reefer madness attack on cannabis, can be laid at the feet of the Spanish Catholic suppression of psychedelic use among the colonized Indians of Central and South America. Substances like cohoba snuffs, peyote, teonanacatl(Psilocybe mushrooms), and ololiuhqui (morning glory seeds) were all, literally, demonized.

That said, there is nothing necessarily demonic or anti-Christian about psychedelics then or now. Before the hippies injected massive doses of pop occultism into postwar psychedelia, a number of significant figures gave a Christian spin on the new alchemy. Captain Al Hubbard was a staunch Catholic who became the Johnny Appleseed of LSD in the 1950s, turning on at least one monsignor and attributing his acid evangelism to an encounter with an angel. During the 1960s, the Boston area not only saw Walter Pahnke’s famous Good Friday Experiment at Marsh Chapel, with Howard Thurman delivering an Easter sermon through a loudspeaker to the trippers below, but also the modest but significant career of Lisa Bieberman, a brilliant and unsung psychonaut who worked to square LSD and Western religion, especially Quakerism. (Please read Bieberman’s crucial 1968 text Phanerothyme: A Western Approach to the Religious Use of Psychochemicals).

Around the same time, the psychiatrist Bill Richards started collaborating with Stan Grof on psychedelic therapy at Spring Grove; decades later, Richards worked with Roland Griffiths to shape the game-changing research program at Johns Hopkins. As his book Sacred Knowledge makes clear, Richards has long brought a gentle but overt Christian sensibility to psychedelic healing, most notoriously through a widely-used trip playlist heavy on requiem masses and Bach. An Episcopal reverend with the excellent name of Hunt Priest, who went through the Johns Hopkins shroomin’ clergy study, was so inspired that he founded a pastoral psychedelic project called Ligare — and stuck with the org even when it got him into hot water with his diocese.

These days, a pro-psychedelic stance is emerging on the edge of mainstream American Christianity. Take, as an example, The Christian’s Guide to Psychedelics, a guidebook recently self-published by Wendi Rees, who records a podcast called Truth Talk whose tagline — Faith, Family, Freedom — probably clues us into her voting behavior. Occupying the Venn diagram between wellness and Christianity, deeply concerned with the traumas of childhood sexual abuse, Rees spends some of her book describing her own healing journey through the “Heart Protocol” (MDMA, psilocybin, and ketamine) as well as later work with ibogaine, which, because of its popularity among vets and Texas legislators, may be on its way toward becoming the most Christian-coded of psychedelic substances.

But Rees spends most of her book directly addressing Christians who are wary of being “deceived” by psychedelics. In his foreword to the book, Adam Marr, who promotes psychedelic healing for veterans, describes Rees’ project as a “powerful call to the Christian world to move beyond fear and stigma and into a higher discernment.”

Using lots of scripture, Rees makes the argument that plant medicines are part of God’s creation, and that there are both godly and ungodly ways of using them, just as there are with wine, sex, and music. Perhaps the most interesting Bible passage she cites is from the First Epistle to Timothy, a probably pseudo-Pauline letter addressed to church leaders at Ephesus:

“Now the Spirit expressly says that in later times some will depart from the faith by devoting themselves to deceitful spirits and teachings of demons, through the insincerity of liars whose consciences are seared, who forbid marriage and require abstinence from foods that God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truth. For everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving for it is made holy by the word of God and prayer.” [4:1-5]

The passage starts out with some good ole Christian demonizing, with warnings about the latter days and devilish deceptions that should sound pretty familiar by now. It’s easy to imagine contemporary believers heeding this passage and putting psychedelics and proponents like Rees and Marr on the side of the Deceiver. But the text goes on to describe ascetic Christian teachers who condemn marriage and certain foods, presumably along the lines of those hard-ass hermits who began fleeing the cities for desert caves the following century. The author of First Timothy condemns these sour naysayers in turn for criticizing God’s creation, and for not recognizing that the practice of thanksgiving and prayer can help make such carnal enjoyments holy. Psychedelics are part of God’s plan for us, Rees insists — even the synthetic ones — and consuming them prayerfully, with a godly “set and setting,” makes all the difference.

Whether or not psychedelics become normalized among conservative Christian communities is not so much my interest. More power to them. What seems important is that believers like Rees and Marr are willing to turn and face the strange, to resist demonizing substances that can occasion weird ecstasies and sometimes ominous enchantments, but that can also afford authentic sacred encounters and much needed balm. And the reason they are willing to make that leap, to push back against Christianity’s deeply ingrained pattern of supernatural paranoia, is because they know that they and others are suffering. Trauma, PTSD, despair, and sexual abuse do not recognize political boundaries, and I would like to think that our shared vulnerability to such wounds demands a certain fellow feeling around healing, even for those across the aisle. Given the increasingly eschatological tenor of our times, and the willingness of so many right-wingers to literally demonize their fellow Americans, this smidgen of shared practice may not amount to much. But it’s not nuthin.

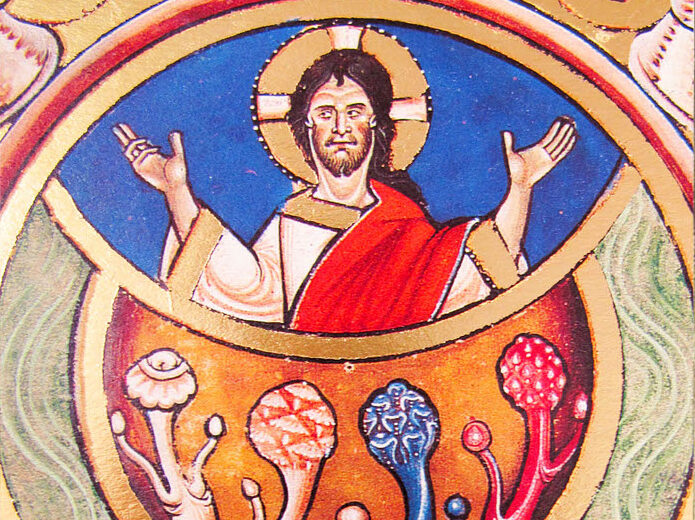

Main Image: From the Great Canterbury Psalter, England, circa 1200.

Get Lucid News headlines in your inbox once a week.

© 2020 Lucid News. All Rights Reserved.