Third-year University of Notre Dame law student Nicolas Munsen has racked up a great deal of real-world legal exploring while studying a very specialized corner of jurisprudence.

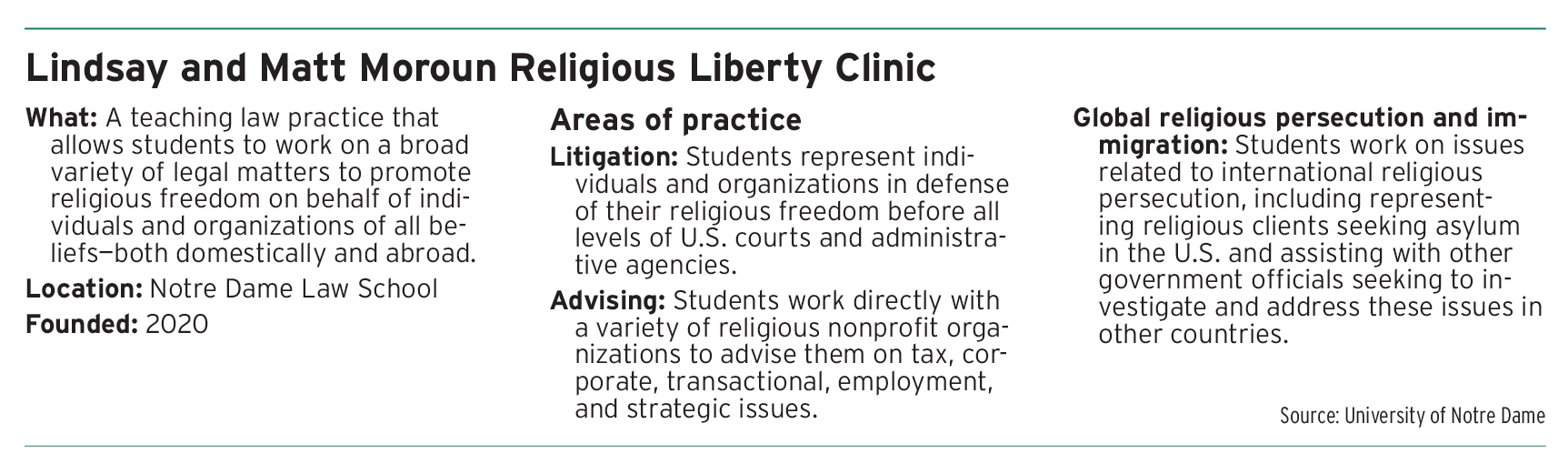

He’s signed on with the Lindsay and Matt Moroun Religious Liberty Clinic, a teaching law practice whose mission is to promote religious freedom for individuals and groups of all belief systems, both in the U.S. and worldwide.

“I’ve worked in both the litigation world and the transactional world,” Munsen said. “On the litigation side, I worked on a case for an organization called Apache Stronghold, which was about protecting the religious freedom of the Apache tribe when the federal government sold a sacred site that belonged to the tribe so that it could be turned into a copper mine.”

Roughly two dozen law students participate in the program at any given time. The Religious Liberty Clinic was founded in 2020 by the Notre Dame School of Law and serves as a teaching law practice that actively participates in myriad religious liberty cases, offering its expertise and services in litigation, transactional advising and in cases involving religious persecution and immigration.

“We’re effectively a small teaching law firm, as all clinics are,” said John Meiser, director of the Religious Liberty Clinic. “Our first mission is to educate Notre Dame law students and give them opportunities to become lawyers by working for real clients in the service of religious liberty, religious organizations and believers.”

The clinic offers the usual classroom work, discussions and lectures. But its unique specialty offers students plenty of chances for hands-on training.

“In addition to what you might think of as your more typical educational environment, the real heart of the clinic is the legal work the students do for the clients,” Meiser said.

The caseload is both varied and exotic, because the clinic doesn’t confine itself to Catholic or even Christian causes. Its collection of clients includes everything from the aforementioned Apache Stronghold case to religious schools in conflict with state and local governments to prisoners of various faiths who believe they have been prevented from worshiping as they see fit.

Meiser said that while many students are attracted to the clinic’s offerings because they’re interested in religious freedom cases, they also appreciate the practical training.

“I think that many of our students are drawn to the really high-level legal experiences we offer,” he said. “There’s not many places in law school where you get the chance to work on a brief that will be filed in the U.S. Supreme Court or at a federal court of appeals. It’s an experience students are drawn to, because it looks different than sitting in a typical lecture-based classroom every day.”

Though law school clinics are a well-worn concept, the idea of dedicating one to religious liberty cases is fairly new — and still fairly rare. Stanford Law School has maintained one for more than a decade, and a handful of others have come into being over the last few years, including at Harvard, Yale and the University of Texas.

“I think it’s a growing community of religious liberty clinics and law schools around the country, but there still aren’t a ton of them,” Meiser said. “But we’re seeing over the last several years that law students around the country are drawn to this opportunity to develop their legal skills in what are not only really important areas of religious freedom, but really fascinating and intellectually engaging areas.”

To call the mix of cases “eclectic” would be an understatement.

“It does sort of run the gamut,” said clinic staff attorney Meredith Holland Kessler, who supervises students in the program’s litigation section. “We do a good amount of work in the education field, working with religious schools who wish to participate in various programs and have been denied the ability to do so because of their particular religious faith.”

The clinic also sees lots of cases involving zoning and land use, ranging from the aforementioned Apache Stronghold case to an amicus brief the clinic filed with the Kentucky Supreme Court in support of the Missionaries of Saint John the Baptist, who sought to build a small grotto similar to the one honoring the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France. The county zoning board initially approved the plan to build the shrine, but a reviewing court reversed the decision. Apparently neighbors of the grotto raised concerns about high traffic in the area — especially if there was an actual sighting of Virgin Mary or a miracle happened there.

“That’s what I mean when I talk about how fascinating some of this stuff can be,” Meiser said. “You don’t expect to see that in your standard federal litigation.”

The methods used by the clinic to find new clients are equally varied. In some instances the staff may hear about an interesting case and offer their services. In others an organization that needs help, or a legal professional who knows about the clinic, may email them out of the blue.

“We of course have a pretty vast network of lawyers and organizations who travel in similar circles in promotion of religious freedom,” Meiser said. “We often refer things to each other. And we’ll often find something through our own research, and we’ll reach out and say, ‘Hey we saw this case you’re working on. Let us know if there’s any way we can help.’”

That assistance can take many forms, from filing amicus briefs on behalf of a client, to serving as co-counsel for attorneys who may lack expertise in the religious issues they’re dealing with in court.

Though he hesitates to list the types of cases the clinic sees the most, Meiser said many come down to matters of fairness and equality — and the right not to be discriminated against simply because of one’s religious beliefs.

“Another one that we participate in a lot, and unfortunately is really needed, is religious exercise in prisons,” he said. “If you are incarcerated, if you’re in prison or a jail, all of your freedoms, not just your religious freedom but all of your freedoms are essentially at the total control of the government.”

For instance, the cinic filed several amicus briefs in the case of an incarcerated Rastafarian man whose dreadlocks were forcibly shaved off by prison staff. The prisoner is in the midst of an ongoing attempt to seek monetary damages, which as of May of this year culminated in a petition for a U.S. Supreme Court review — a petition supported by another amicus brief from the Clinic.

“I think we also see a lot of things that are about what I could call conscience rights,” Meiser said. “The right to say that there are times when people should not be coerced into performing actions that violate their core religious beliefs. And if religious freedom means anything, it means the freedom to abstain from certain conduct.”

For instance, roughly 18 months ago the clinic led a federal appeal in Georgia for a man who was excluded from a volunteer prison ministry program because the local sheriff disagreed with his interpretation of Biblical scripture. Specifically, about whether it was necessary to be baptized.

“The sheriff wrote him a letter saying, ‘You’ve interpreted the Bible wrong,’” Meiser said. “He filed a lawsuit with some lawyers down in Georgia, and it was dismissed, so he appealed. His lawyers reached out to us and asked if we’d be interested in helping lead the appeal. So that’s exactly what we did.”

Though the clinic indeed sees a lot of cases, there’s probably not enough of them out there for young attorneys (or at the very least, a lot of young attorneys) to specialize in the field once admitted to the bar.

“We certainly hope that the experience in our clinic would help students who are really interested in specializing in this to gain the experience and knowledge that will increase the likelihood that they can do it at some point in their career,” Meiser said. “But most of our students will likely not become specialized religious liberty lawyers. It’s not a huge area of legal practice.”

Kessler said the clinic encourages its students to develop a mindfulness about such issues so they can help whenever legal conflicts over religion happen to arise.

“So I do think many of our students will go on to do this work in some capacity,” Kessler said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.