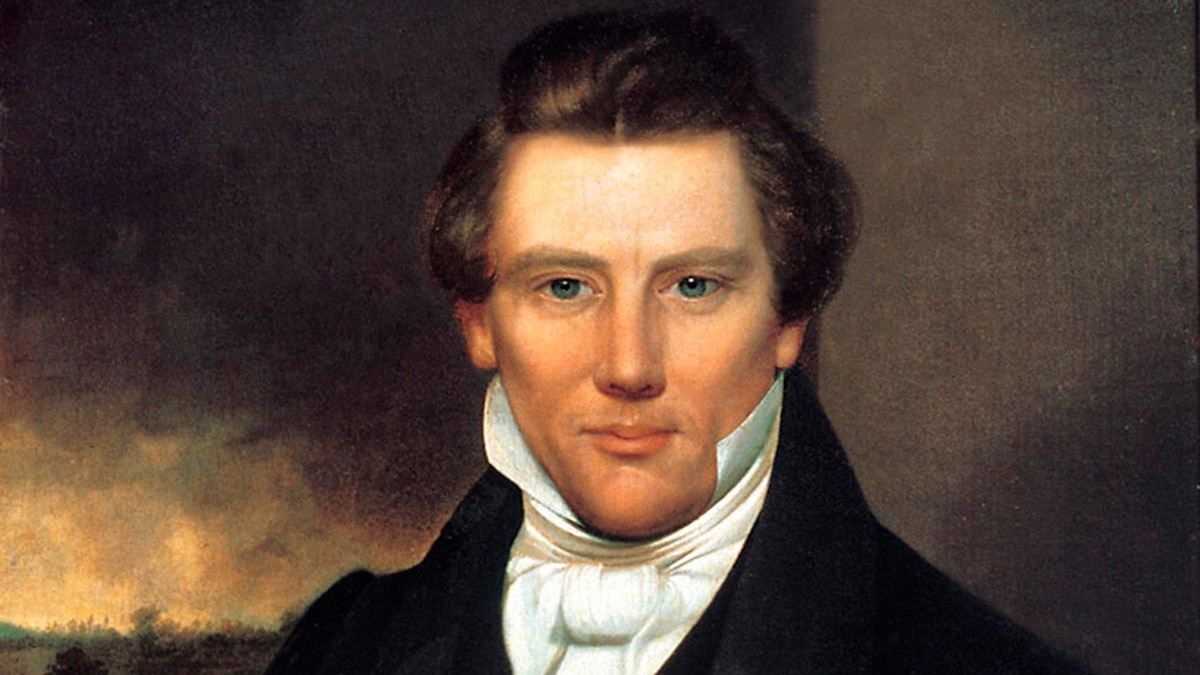

The founder of the Mormon Church rocked 19th-century America with his spiritual visions, his belief in polygamy—and even a presidential run.

Almost two hundred years ago, a farmhand named Joseph Smith founded a Christian denomination that would become one of America’s best-known religious groups: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, otherwise known as the Mormon Church. So how did Smith, a young man from a family of modest means in upstate New York, change American Christianity forever? It started with a vision of golden records—one that led Smith to found a church, move his flock west, take multiple wives, and even run for president.

Joseph Smith was born in eastern Vermont, a middle child tucked into a family of few means. His parents were “often at the precipice,” writes George Mason University professor John Turner, author of the newly published Joseph Smith: the Rise and Fall of an American Prophet. They moved from place to place in search of work and opportunity, starting over and reinventing themselves each time. A comfortable life was often within grasp only to be yanked away by bad luck and circumstance: a foolhardy investment in Chinese ginseng, and an unhappy run-in with typhoid fever that nearly killed young Joseph and his sister and depleted the family’s savings, are just two examples. A famine in 1816, caused by a volcanic explosion in Indonesia that led to global cooling, pushed the Smiths—and many other Vermonters—west to upstate New York. After a year without summer in Vermont, the prosperous region that lay on the planned canal route between the Hudson River and Lake Erie looked like the land of opportunity.

In the 1820s, Palmyra, New York, was a town on fire with economic hope and religious revivalism. There, a young Joseph Smith had the opportunity to witness many a camp where people threw themselves on the ground and writhed with the spirit. The 14-year-old became concerned about the fate of his own soul. Retreating to the woods to pray, he later said in his spiritual writings that he found himself attacked by darkness before receiving a vision in which two glorious “personages” appeared in the air before him. One gestured to the other and instructed Smith, in a phrase evocative of the baptism of Jesus in the Gospels, “This is my beloved son. Hear him!” Smith asked Jesus which church he should join and claimed he was told, “None of them, for they were all wrong.”

Smith’s Methodist minister was underwhelmed by the account and told Smith that “there was no such thing as visions or revelations in these days.” Still, Smith had been raised in a household where dreams and visions were taken seriously. His mother, Lucy, recorded both her and her husband’s dreams for posterity and the family was often mocked by neighbors for their attempts to use divining rods to search for buried treasure, Turner writes. (A scholar of religious studies and history, Turner is one of the rare non-Mormon experts on Smith’s life.)

Joseph Smith himself was attracted to a form of divination known as a “seer stone.” He became a “glass looker,” someone who located objects by looking into rocks or pieces of glass. On one occasion, he had a group of men dig a 50-foot-tunnel based on a vision of money buried inside. The excavation was futile but shows, Turner says, that many around the teenage Smith believed in his visions.

In the ensuing years, Smith claimed, he continued to receive supernatural visitors. In September 1823, he said, an angelic being—later identified by Smith as the angel Moroni—revealed that Smith’s sins had been forgiven and told him about “plates of gold” buried nearby. The angel, Smith said, delivered a potted history of the Americas in which descendants of Abraham had journeyed to the country and Christ had delivered the fullness of the Gospel to these ancient Americans.

Using a newly acquired light-colored seer stone and the instructions he believed to be provided by Moroni, Smith travelled a few miles south of his home where he claimed to find a stone box containing golden tablets. According to Smith, despite his best efforts, he was unable to retrieve the plates and the angel told him to return, which Smith decided to do in a year with his older brother Alvin. But things did not go smoothly, Alvin—Joseph’s hero and in many ways the family breadwinner—died before retrieving the tablets and Joseph was forced into a position of responsibility in the household. He spent some time working for others as a (failed) silver-seeking seer and was arrested on at least one occasion and accused of being “disorderly person” and “an imposter.”

Still, the period was not without fruit. He persuaded Emma Hale, a Methodist from a more affluent home, to marry him. Their elopement ruffled some feathers. Though he had promised Emma’s father that he would settle down and focus on providing for his family, Joseph Smith did not stop looking for the plates. In September 1827, an annual pilgrimage brought him back to the hill in search of the treasure. This time, Smith claimed, the angel made good on his promise. Smith’s mother wrote that he also claimed to have found two stones in silver bows At first, he called them spectacles and later referred to them as Urim and Thummim (names derived from the Bible that refer to objects placed in the Israelite hero Aaron’s breastplate).

No one other than Smith ever saw the gold plates, though others said they witnessed them in visions. According to Smith’s description in his papers, they were thin, had the appearance of gold, and were covered with engraving. They were similar—as Sonia Hazard, an expert on religion in the early United States, has written—to the kinds of plates used at printing presses. Smith later said that the characters engraved on the plates were read right to left, as Hebrew is.

(What archaeology is telling us about the real Jesus)

From the beginning, some had their doubts about Smith’s claims. If Smith did find golden plates, he certainly had good reason to keep them hidden: they were supposedly made from a precious metal, and someone could easily have stolen them. His family members were convinced, but none of them ever saw the plates directly, either. The first people to claim to have seen the plates were referring to a visionary experience. Later witnesses testified that an angel appeared and allowed them to hold the tablets. Their testimony emerged as Smith’s plans to publish a book reached fruition. In 1830, the same year that Smith paid to have the Book of Mormon printed in Palmyra, he organized the Church of Christ (distinct from the Church of Christ today), members of which would later be called Latter-Day Saints or Mormons.

Smith said that the Book of Mormon was a “translation” of the gold plates, but the accounts given by observers of the writing process sound more like dictation. Smith set the Urim and Thummim in a hat and then dictated the words that he claimed to see to scribes: schoolteacher Oliver Cowdery, wealthy Palmyrene supporter Martin Harris, and his wife Emma. All three scribes were convinced of the authenticity of the dictation. Martin Harris even mortgaged his farm to finance the book’s printing. He lost his investment.

The Book of Mormon brought attention to Smith, not all of which was good. Smith was once again arrested and had to grapple with the competing claims of some of his followers that they had revelations themselves. Smith dispatched a missionary group, led by Oliver Cowdery, to the west to preach to Native Americans. On the way, they converted a large congregation in northeastern Ohio under the leadership of Sidney Rigdon, a well-known minister of the Disciples of Christ movement. Almost overnight, the fledgling Mormon church—still numbering only a few dozen in New York—gained several hundred new adherents in Ohio, making it the strongest concentration of members anywhere.

At the same time, Smith announced a revelation instructing the Saints to gather in Kirtland, Ohio, where they could build a community, strengthen the church, and prepare for future expansion into Missouri, which he identified as the ultimate site of Zion. It was during this early expansion that Brigham Young, a Vermont-born craftsman and preacher, encountered Mormonism. Baptized in 1832, Young traveled to meet Smith and quickly committed himself to the movement. He became one of Smith’s most loyal and energetic missionaries, known for his pragmatism and organizational skill. In Kirtland, Young rose in prominence, eventually being called as an apostle in 1835. His early leadership in these formative years, when the church was still fragile and often under attack, positioned him for future leadership.

(The real history of Utah's Mountain Meadows Massacre)

Arguably the most well-known and controversial of Smith’s endeavors was his embrace of polygamy—at first in secret. His interest in plural marriage began with Fanny Alger, an attractive servant girl who lived in his home and was 10 years his junior. Whether their relationship was a simple affair or a plural marriage is debated. Oliver Cowdery himself described it as a “nasty, filthy scrape/affair.” Rumors of adultery swirled around Smith, damaging his reputation and eventually forcing him out of Kirtland, Ohio. As for Alger, Emma Smith reportedly turned her out of the house in the middle of the night. Joseph asked a trusted friend, Levi Hancock, to get Alger out of the way. She ended up marrying outside the church and eventually drifted away from the religion entirely.

The Alger affair is considered by some church members to be Smith’s first step towards polygamy. By the time of his death, he had married more than 30 women and been sealed to them for all eternity. Many were married or very young (two—Helen Mar Kimball and Nancy Winchester—were 14, ten were under the age of 20) when they entered into unions with Smith. Some were promised spiritual rewards for themselves and their families. Smith told his already-married future wife Zina that an angel would kill him if he did not go ahead with the marriages. Some women were willing to enter eternal unions with Joseph and some, like Zina Huntingdon, remained with their first husbands after the ceremonies. Some, like Mary Rollins Lightner, were pregnant with their first husband’s child at the time of their union. In one instance, Joseph was sealed first to Sylvia Lyon, whose wedding he had presided over some years earlier, and then later to her (also married) mother, Patty.

Some of these marriages were about fortifying social ties between Smith and other leading families in the movement, Turner notes. “A good number of the marriages were consummated, and Smith seems to have been smitten with at least a few of his plural wives. There wasn’t a great deal of sex, though, as evidenced by the fact that none of the plural marriages produced known children,” he says.

(Can religion make you happy? Scientists may soon find out.)

There was a theological and biblical basis for plural marriages, but the proposal was still a shocking one for 19th-century Protestant American society. According to late 19th-century independent historian Andrew Jenson, the principle was first revealed to Joseph in 1831 but he was forbidden to make it public for over a decade. Theologically, the rationale seems to have been increasing an individual (man’s) eternal glory. “Smith taught that the purpose of earthly existence was male exaltation unto godhood,” explains Turner. “One requirement for exaltation was marriage through the priesthood authority of Christ’s one, true church. But there were degrees of exaltation, degrees of eternal glory, and Smith seems to have connected the extent of one’s eternal glory to the size of one’s earthly family. That’s why he pursued such a large number of polygamous marriages.”

Polygamy, which was only permitted for Mormon men, sparked a backlash first among insiders and then in wider society. Initially some early Latter Saints—for example William Law, a prominent member of the church hierarchy—resisted or left the church when they heard of it. Opposition culminated in an exposé in the Nauvoo Expositor in 1844, in which Smith and polygamy were denounced. Because polygamy was practiced secretly, only a few other Mormon leaders like Brigham Young, Herber Kimball, and Willard Richards entered in plural marriages during Smith’s lifetime.

By the end of the 1830s, the Latter-day Saints found themselves caught in a cycle of settlement and expulsion that would shape the course of their history. In Missouri, tension over religion, politics, and land ownership spiraled into open conflict during the Mormon War of 1838, culminating in Governor Lilburn W. Boggs’s Extermination Order, which declared that Mormons must be “exterminated or driven from the state.” Violence soon followed: mobs attacked Mormon communities, most notoriously at Hawn’s Mill on October 30, where 17 men and boys were slaughtered without quarter. Thousands of Saints were forced from their homes, crossing the Mississippi River into Illinois in the dead of winter.

At first, Illinois offered a new beginning. The Saints drained swamps along the Mississippi and built the thriving city of Nauvoo, complete with its own militia, courts, and a majestic temple. But as the city swelled with thousands of converts from across the United States and Europe, neighbors grew uneasy. Smith, serving simultaneously as mayor, church prophet, and commander of the Nauvoo Legion, embodied a kind of theocratic authority that alarmed outsiders. Rumors of polygamy, combined with the rapid political rise of the Saints, fueled suspicion and resentment.

In the face of mounting opposition in Missouri and Illinois and with appeals for government assistance going unheeded, Smith attempted to run for higher office. In January 1844, he announced his candidacy for President of the United States. In his platform, General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States, he called for a stronger federal government to protect minority rights and religious liberty, the abolition of slavery through compensated emancipation, and reform of the justice system. He also advocated for expansionist policies, including the annexation of Texas, Oregon, and other territories.

After the exposé by church dissidents in the Nauvoo Expositor, Smith ordered that the press be destroyed. The governor of Illinois, Thomas Ford, ordered that Smith stand trial for instigating a riot. Smith was arrested and, before he could stand trial, assassinated by a mob in Carthage Jail. Violence spilled into the streets, homes were torched, and gunfire echoed along the Mississippi in what came to be remembered as the Illinois Mormon War. Within two years, under relentless pressure, the Saints abandoned Nauvoo, launching their legendary westward exodus. For Mormons, these ordeals—Missouri’s extermination order and Illinois’s mob violence—became enduring symbols of persecution and resilience, marking the crucible from which a new religious tradition would march toward the deserts of the American West.

Smith loved adventure, Turner notes, adding the Mormon founder “found risk thrilling. He loved dashing through the woods and dodging enemies. He enjoyed marching to Missouri with scores of other church members. The secret pursuit of polygamy was also exhilarating, and even though the stakes were high, so was hiding out from lawmen.”

For his new book, Turner immersed himself in the many writings of Smith, his friends, and his opponents. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and other organizations also made their extensive archives available to him. The main impression he gleaned of Smith was of his audacity, he says. Smith published a new Bible, started a church, mobilized church members to move to the frontier in anticipation of Christ’s return. He started a bank and even ran for president. And for every setback, there was a fallback plan. Even in his last moments he was attempting to make his escape from the Carthage jail through a window.

When Smith was killed in June 1844, the Latter-day Saints plunged into a succession crisis with no clear line of authority. Several contenders stepped forward. Sidney Rigdon, the last surviving member of the First Presidency, the highest governing body of the church composed of the prophet-president and his counselors, argued he should be the church’s “guardian.” James Strang brandished a supposed letter of appointment from Smith (Strange would go on to establish his own movement and claimed to discover his own scriptural plates).

As president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the second-highest governing body charged with carrying the church’s authority when the First Presidency was not functioning, Brigham Young claimed that Smith had given the Twelve the full “keys” of leadership. At a meeting in Nauvoo on August 8, 1844, Young delivered a speech that many witnesses described as uncannily evoking Smith in voice and appearance, an impression that persuaded the majority. The Saints voted to follow the Twelve, and Young quickly consolidated power by overseeing the completion of the Nauvoo Temple and later leading the migration west.

Emma Smith clashed with Young over polygamy, the internment of Joseph’s remains, and her children’s legacy. She remained in Nauvoo and remarried in 1847. Up until her death, Emma continued to deny that her husband practiced polygamy. Most of Smith’s other plural wives followed Young west. Many remarried and some of those, like Zina Huntingdon, were married to Young himself.

The 19th century was a period of charismatic religious leaders. Most have fallen into obscurity and are remembered only by historians. But Smith, writes Turner, left “indelible marks.” Millions of Mormons continue to participate in the rituals and church that he founded. “Mormonism,” says Benjamin Park, author of American Zion: A New History of Mormonism, “is arguably America’s most successful homegrown religion.”