Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

© 2023 The Christian Century.

Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Please, liberal Christians, read Eugene Peterson

I’m not too proud to beg.

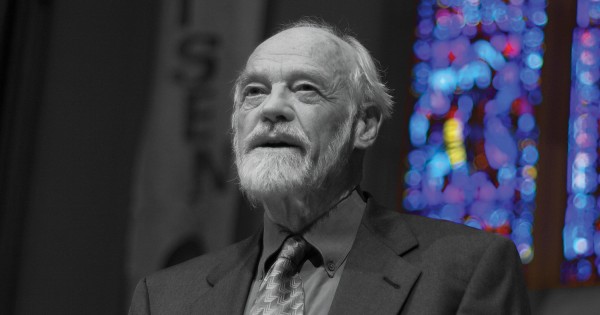

Eugene H. Peterson (Source photo: Clappstar / Creative Commons)

I am sitting in a study overlooking Flathead Lake in Montana. The west wall is lined with bookshelves from floor to ceiling. What surely must be complete collections of Wendell Berry’s and Karl Barth’s works catch my eye; I suspect the volumes of Church Dogmatics are first editions. The lowest shelves hold Eerdmans’s Theological Dictionaries of the Old and New Testaments, stretching on for 27 thick tomes. There are bookshelves on the east side of the study too, below windows that let in so much morning sunlight I nearly need sunglasses indoors. Ceramic tiles depicting the Stations of the Cross line the windows, the handiwork of the Benedictine monks of St. Andrew’s Abbey in the Mojave Desert. My friend Eric Peterson invited me to write here for the week. This is the study where his father, Eugene, wrote books.

I picked up my first Eugene Peterson book a couple of months after my ordination, 20 years ago. My whole first year as a pastor, I vacillated between queasiness and low-grade panic. Seminary hadn’t fixed the tiny complication I carried with me throughout my theological education: I didn’t know God. I mostly believed in God, intellectually. I sort of loved God, theoretically. But I had never tasted and seen that the Lord was good. The closest I’d gotten to faith was wanting to believe. The tangibility of Jesus resonated, but post-resurrection Christ seemed little more than an imaginary friend. Meanwhile, I’d gone into ministry because of a deep hunger for God, and now I found myself consumed by the logistics of running a church. Why on earth had I felt called to become a pastor if I was never going to experience the grace of God and the consolation of faith?

Subscribe

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Many of my peers in the liberal mainline tradition seemed content to shake off personal piety in favor of a ministry oriented toward social justice. But I was desperate for an encounter with the holy. I can’t say why Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places caught my eye at a bookstore. I did not have a favorable impression of Peterson, having been led to believe by my seminary professors that The Message, his biblical paraphrase, was akin to a peanut butter sandwich with the crusts cut off. But I bought the book, and it changed my life. A few months later, at the same store, I found a battered copy of Working the Angles, and it changed my ministry.

Peterson wrote about God with intimacy and imagination, authority and agitation. Where Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places was literary and expansive, Working the Angles felt like a trip to the principal’s office. Peterson was tired of pastors abandoning their vocation in favor of trendy church growth crap. Get back to the basics, he barked. Praying. Reading and proclaiming scripture. Giving spiritual direction. I loved that he made it seem like the stakes were steep, like what we did as pastors mattered enough that it would be treacherous to do our work inadequately and with our attention attuned to the wrong things.

I went on to read book after book, attend Peterson’s last offering of his Writing and the Pastoral Life workshop, craft a grant-funded sabbatical inspired by the “Unbusy Pastor” chapter in The Contemplative Pastor, and receive one of the first doctor of ministry degrees granted through the Eugene Peterson Center for Christian Imagination at Western Theological Seminary. I still have the voicemail in which Peterson said he’d contribute the foreword to my book on marriage.

And yet, I don’t really think of myself as a fan of Peterson. He is one of my pastors. Winn Collier, my mentor in the doctoral program, was clear that we were not there to put Peterson on a pedestal, and that Peterson himself would have hated that. God, not Peterson, was the “burning center” of every worship service, every class, every conversation, every friendship, every project. Here was the spiritual formation I had desperately missed in my first go-round of theological education. During our first doctoral intensive, Winn named a truth that captured my reaction to Peterson’s work all those years before: “In Eugene’s writing, we encounter something about God we can’t know alone.”

Yet I’ve often found myself alone as a reader of Peterson’s work—or at least, alone among my closest clergy peers. I made two really good friends at the Writing and the Pastoral Life workshop—the kind of friends with whom I’ve traveled for family vacations—and neither of them responded to Peterson with the same fervor as I did. When I’ve been in clergy book clubs, not once did any of his pastoral theology books make the cut. And when I shared my excitement about having been admitted to the doctoral program with some colleagues in the United Church of Christ, the news was met with cool bemusement. Why was I so keen on a White guy whose theology was insufficiently liberal and who failed to publicly affirm the full inclusion of LGBTQ people? Wasn’t he kind of an evangelical?

Peterson wasn’t an evangelical in the contemporary sense of the word, and he was deeply uncomfortable in most evangelical spaces, particularly the megachurch variety. Theologically, he was more traditional than many of my colleagues, but the edges of his orthodoxy were gracious and beautiful, never harsh or unkind. In any case, his theology was not what I found most compelling in his work, especially in those early years. It was his wisdom in challenging the pastor to never condescend to the congregation. It was his humor; when Peterson realized that the people receiving his regular reports about his brand new congregation clearly weren’t reading them, he started peppering them with hilariously scandalous falsehoods. It was his brilliant tactic of penciling in two hours with Dostoevsky every Thursday afternoon and simply telling people who asked to meet with him during that time that he was already booked. It was sentences like this one, pulled at random from a notebook in which I’ve jotted down countless Peterson quotes: “God’s love will burn deep into our lives, penetrating habits and dreams until it ascends into flames of joyous adoration” (from Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work).

Above all, it was his insistence that we live and minister as if God is real. Peterson is the person who taught me, at long last, to pray. I did not need to agree with everything he thought, even about some things that matter a great deal, to be grateful on an eternal scale.

Given how few of my mainline clergy colleagues in my generation read Peterson, I wasn’t surprised that I was the only pastor in the doctoral program who came from a liberal tradition—and the only woman. I was sad, however. I’ve always had an impulse to share the things I love. (I am personally responsible for creating hundreds of Over the Rhine fans, so effusive and effective am I in sharing my undying love for their music.) And I love Peterson’s books. I wouldn’t keep reading them if his voice didn’t keep inviting me into the presence of God in a way that no other author has.

I’ve been conspiring to remedy the Eugenelessness of mainline Christians’ minds and hearts. I’ve considered writing a book that translates Peterson’s wisdom for contemporary pastors—Reclaiming Contemplative Ministry in the Secular Age—but at this stage of my life and ministry, I can’t write a book and maintain an unbusy pastoral posture. Using funds from a Louisville Institute pastoral study grant, I once actually paid pastors to read one of his best books and tell me what they thought. With precious few exceptions, the ones who had never read him before—whether as an act of intentional protest or by mere chance—were surprised to find at least a handful of reasons the book was worth their time (and the Lilly Endowment’s money).

Ultimately, when I sat down in this perfectly appointed study in the Peterson home this morning, untouched since Eugene’s days, I decided I’m not too proud to beg: Please read Eugene Peterson. You could start with Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places, though Answering God might be my favorite. Eat This Book made me fall in love with scripture all over again, and Where Your Treasure Is may well be the only thing keeping me from losing my mind during the second Trump administration.

And if you are a pastor, for the love of the God who is sweet like huckleberries on my tongue: Please read Peterson’s pastoral theology. Read Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work. Read Working the Angles. Read Under the Unpredictable Plant. Read The Contemplative Pastor. Read The Message. I can’t pay you. You’ll just have to take my word for it.

Katherine Willis Pershey is copastor of First Congregational United Church of Christ in Appleton, Wisconsin, and author of Very Married.

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about this article by writing a letter to the editors.

by Nick Peterson

Art that stretches us

Illuminating the icons

When Caesar gets demanding

The reverent, subversive Gilead

Facing fascism

A musician meets Flannery O’Connor at the crossroads

Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

![]()

![]()

© 2025 The Christian Century. All rights reserved.

Contact Us

Privacy Policy