Advancing the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

Justin Giboney

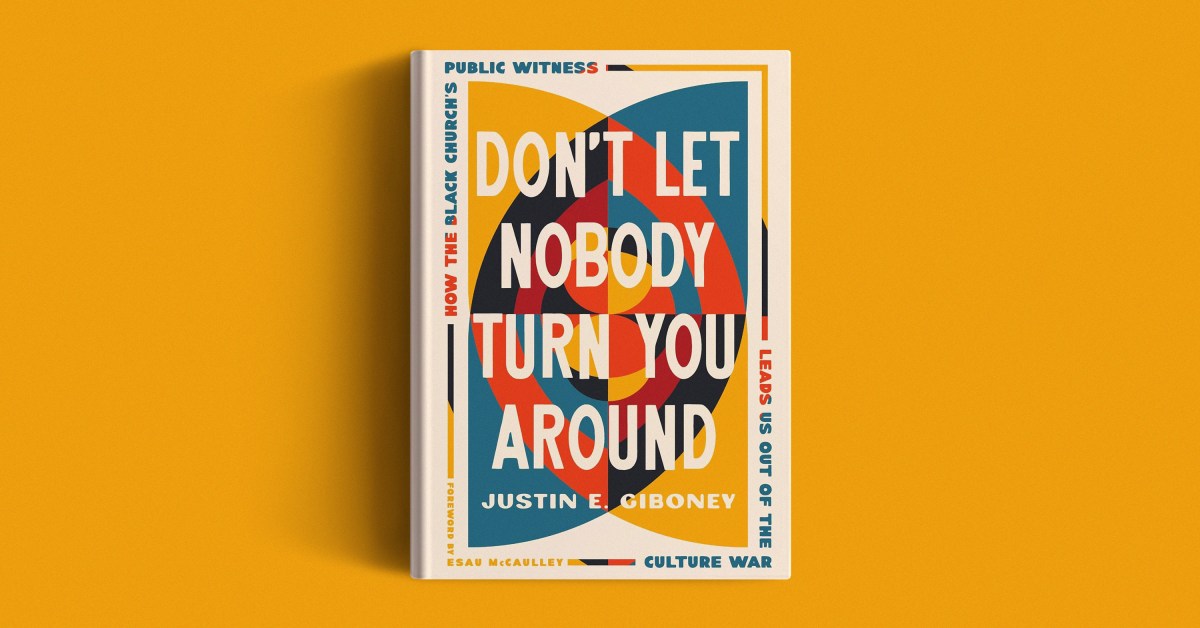

An excerpt from Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around on family history, gospel music, and the great Christian legacy of the Civil Rights Movement.

My maternal grandmother, Willie Faye, was born in Forest, Mississippi, in 1932. That’s the same year segregationist Martin “Sure Mike” Conner was inaugurated as governor of Mississippi.

From Reconstruction to the 1950s, Mississippi had more lynchings than any other state in the Union. Accordingly, Willie Faye’s parents kept a shotgun by the door to protect the family in case the Ku Klux Klan decided to pay them a visit and tried not to leave the house after sundown. Fearing the false allegations of looking at a White woman inappropriately, her first cousins, Billie and Buford, fled the state as teenagers.

Yet Conner, a Yale-educated lawyer, practically ignored this violence while endlessly railing against the federal government and President Roosevelt’s New Deal for “meddling in the race question” and treading on states’ rights.

Each issue contains up-to-date, insightful information about today's culture, plus analysis of books important to the evangelical thinker.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for signing up.

Explore more newsletters—don’t forget to start your free 60-day trial of CT to get full access to all articles in every newsletter.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

Named after her father, Willie Frazier, Willie Faye—or Faye for short—was the sixth of eight children. By natural disposition, she became the glue binding a house full of conflicting personalities together. She found herself playing the role of mediator, defusing in-house rivalries and settling disputes. The siblings would have to pick cotton to help make ends meet, and they often went shoeless as they labored in the heat of the Mississippi Delta for depressed wages that weren’t magically corrected by the invisible hand of the market. Early on, she vowed that her future children would never pick cotton or go shoeless.

Justin Giboney

Stephen R. Haynes

Unlike Governor Conner, Faye would not attend an Ivy League school or any college at all. She’d leave high school at the age of 16 to get married. According to her mother, this was the best option given the social location of a Black woman of her day, and by this time, her family had uprooted and moved to Decatur, Illinois, in search of greater social justice and economic opportunities.

Before leaving school, Faye sang in the Colored Girls’ Choir at Stephen Decatur High School. She also sang in the choir of her Black Pentecostal church and developed a passion for the formation and Christian education of children. Faye loved gospel music. Every Saturday morning when she cleaned the house, there was one voice her three children were sure to hear: Mahalia Jackson.

Known as the Queen of Gospel Music, Jackson was her favorite artist—a muse Willie Faye would cherish in mundane, celebratory, and disheartening moments for decades. Her voice would pierce through denominational walls and inspire singers like Aretha Franklin. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would say, “A voice like [Mahalia’s] comes along once in a millennium.” It’s been described as not a voice but a force of nature.

Mahalia, or “Halie” for short, was born in New Orleans in 1911. She grew up in the Black Pearl section of the city in a three-room house with 13 family members, including aunts and cousins. Her mother, Charity, died when she was five years old, leaving her with her Aunt Duke, a stern disciplinarian.

Three of Mahalia’s nicknames from childhood provide insight into her early social experience: “Hook” referred to her severely bowed legs and crossed feet, “Black” referred to her dark complexion, and “Warpee” was the name of a Native American character who walked around barefoot, as Mahalia often did because she couldn’t afford shoes.

While the nicknames were often repeated affectionately, they exposed real pain points in her life. Born with deformities, with dark skin in a colorist society, and in poverty, Mahalia was about as far from privilege as one could get. Her ascribed status didn’t provide her with any advantages, but her faith, her diligence, and her voice would distinguish her in due time.

Jessica Janvier

Haleluya Hadero

Mahalia left school before finishing fourth grade to work and tend to family. However, her experience overcoming her disadvantages in a harsh urban environment developed a “mother wit” that’d eventually make her a wise counselor and formidable businesswoman. And throughout a very rough childhood, Mahalia always had the church.

Her maternal grandfather, Paul Clark, was a Baptist preacher, and from a young age, she was known as a prayer warrior who almost never missed a church service. She sang her first hymn at four and was capturing the audience at Mount Moriah Baptist Church by 14.

Willie Faye and Mahalia shared a common American experience viewed through the lens of faith. Both Black women were born deep in the Jim Crow South and reared in the traditional Black church. The stench of slavery still lingered in the air of their environment and was visible in the scars of the family members who shaped their worldview. Both were nurtured by elders who were formerly enslaved themselves. They were cautioned by the wisdom of the enslaved and emboldened by the courage of those who’d survived America’s original sin.

These women lived in an era that some have called America’s Second Slavery. Even after Emancipation, Black labor was still being stolen through the sharecropping system, and racial injustice was upheld in courts of partiality. Additionally, white supremacist defenders of the Lost Cause believed it their calling to literally terrorize the Black community to maintain political and economic dominance. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, almost two or three Blacks were lynched every week in America.

As Willie Faye and Mahalia were coming into womanhood, the “progressive” eugenics movement was giving “false scientific legitimacy” to forced sterilization. As a result, tens of thousands of Black women were victimized by non-consensual sterilization, including Civil Rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer, who called it a “Mississippi Appendectomy.” They both journeyed to escape Jim Crow’s jurisdiction but would still endure racism with a different accent and Midwestern flavor.

Bryan Loritts

Stephen Newby

Willie Faye and Mahalia’s story is the story of the Black church’s Civil Rights generation, a generation whose Christian faith and social action prowess provided us with perhaps the greatest illustration of moral imagination in America’s history. For the purposes of this book, Willie Faye and Mahalia’s generation are those who served as the base of the Civil Rights movement—the progeny of the enslaved and the fruit of the Black church.

They were Black Americans for whom the Christian church served as the center of spiritual, social, and political life. They talked about morality and heaven, but unlike the white evangelical church, they didn’t limit God’s will in the public square to personal piety. They recognized social justice as a required part of the kingdom plan.

Unlike secularists, they clearly didn’t interpret the separation between church and state to be a severing of one’s faith from their sociopolitical engagement. Faith guided and anchored their social action.

Unlike the social gospel of today’s progressive Christians, they believed the “whole counsel of God” was more than the justice imperative alone (Acts 20:27, RSV). It also involved the Bible’s tenets about sin and how sin exists in all of humanity, not excluding their community or themselves.

Lastly, unlike much of Black secular activism, while it understood that “power concedes nothing without a demand,” they believed their social actions had to be aspirational, holy, and redemptive and that no group of people, not even their oppressors, was irredeemable. Willie Faye and Mahalia’s generation were not the originators of the Black church’s social action tradition, but they were perhaps its crown. They grasped the legacy and the lessons they learned from their elders and took “bigger steps and bigger risks.”

Jonathan Tremaine “JT” Thomas

Justin Giboney

While Mahalia grew up in a Baptist church, when she moved to Chicago it became clear that she’d been heavily influenced by the sound of the Black Pentecostal church a few doors from her home in New Orleans. Many of the Baptist churches in Chicago didn’t appreciate the impassioned shouting and improvisation in her style. Gospel singer Sallie Martin said that early on “most of the big churches still didn’t receive her work. … Some were very, very much against her—and other singers looked down their noses at her.”

Denominationalism and classism were at play here. Many Baptists considered their music refined, unlike the frenzied shouting of lower-class Pentecostals in what was called the sanctified church. But Mahalia would eventually compel some resistant Baptist audiences to “get happy” and applaud a more Pentecostal approach to worship.

Today, the Black Baptist church I attend welcomes shouting and impassioned praise, in large part based on Jackson’s legacy. She was the intoning voice of a generation of women who nurtured and powered churches, communities, and a social movement—women like Willie Faye who fed and supported the leaders before and after they preached and protested. But her voice didn’t just impact the women of her time; it became the pitch for the Civil Rights generation in general.

If the Civil Rights Movement had theme music and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s visionary words were the bars that laced the track, then Mahalia’s riveting contralto blessed the chorus, melodically expressing the ethic and motif of this world-changing social composition.

She sang her signature versions of the songs “How I Got Over” and “I Been Buked and I Been Scorned” at the March on Washington in 1963 before Dr. Martin Luther King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. During the speech, in the Black church’s time-honored call-and-response tradition, she would shout, “Tell ’em about the dream, Martin. Tell ’em about the dream.”

That theme wasn’t in his notes, and he hadn’t originally intended on mentioning it that day. But Mahalia had heard Dr. King speak about “the dream” in other addresses and had experienced its power. As fate would have it, her encouragement might have catalyzed the most memorable lines of one of the greatest speeches in American history.

Justin Giboney

Sho Baraka

How often did Willie Faye and hundreds of thousands of other Black Christians in her generation find respite in Mahalia Jackson’s voice? How often did they remove their soiled aprons and weathered fedoras after enduring another day of subordination and segregation and pull one of Mahalia’s records from its sleeve?

I imagine, almost out of necessity, they put the vinyl on the turntable, carefully placed the phonograph needle down, and through her spirituals were persuaded or even compelled to push forward another day. Or perhaps some tuned in to her weekly CBS radio program, sank into the couch, or prepared soul food supper and let her powerful articulation of the sanctified gospel heal their souls.

Their pain was too real and direct for this to have simply been a routine or formulaic exercise. No, this was soul-penetrating praise and worship in the spirit of the prophet Jeremiah and King David. It was embattled petitioners saying, “Lord, hear my prayer, listen to my cry for mercy; in your faithfulness and righteousness come to my relief” (Ps. 143:1).

Through the music, we see how the spiritual and the sociopolitical were seamlessly tied together in the Black church social action tradition. The spirituals they sang in church were the same spirituals they sang during marches and protests. In church, they’d sing about faithfully pursuing God:

For a social action march, they might adapt the song by singing,

In the same vein, the song “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” one of the most recognizable Civil Rights spirituals, was an adaptation of “Keep Your Hand on the Plow,” a gospel song based on Luke 9:62. Negro spirituals were ever present in the Civil Rights Movement. It was a way for Black Christians to take the church with them as they journeyed outside the four walls of the sanctuary. By singing spirituals in the field of life, Willie Faye and Mahalia’s generation was continuing a legacy of placing God at the center of their interactions in the world.

Daniel K. Williams

Jessica Janvier

Black Christians in that generation greatly invested in the church and made major sacrifices for it. Some weeks, Mahalia would be exhausted after five straight nights of revival singing at Greater Salem, where all the proceeds would go to the programming for the children’s ministry, “so those children wouldn’t have to run around the streets.” Faye and her husband, Bishop Thomas L. Cooper, helped build Church of the Living God, Pillar and Ground of the Truth, Temple #1 brick by brick and paid off the last of the mortgage for Temple #2 out of their own pockets.

The Black Church’s social action, at its best, was a negro spiritual in action. While the Black Church was far from unanimous in its support of social activism, “from the beginning, the Civil Rights Movement was anchored in the Black Church.” Preachers and the people in the pews organized and financially supported the movement. Again, Willie Faye and Mahalia’s generation of Christian advocates didn’t disconnect the sacred from their engagement in the public square.

Some secular movements have interpreted religion and talk of faith and heaven as merely a form of escapism—a means of disengaging from reality. But for many the hymns helped them better engage reality. There were indeed those in their community who tried to dismiss the here and now by solely focusing on the hereafter. However, the Civil Rights Movement was the opposite of escapism. It was an action-oriented initiative with a keen awareness of the principalities and spiritual wickedness in high places at play in society.

Social justice outside of the existence of a loving and just God doesn’t make sense. The worldview at the center of the Black church’s social action tradition rejected the idea that this miraculously designed world came from nothingness. A godless particle or uncreated big bang couldn’t possibly create Mahalia’s voice, Zora Neale Hurston’s prose, George Washington Carver’s scientific mind, or a slave’s moral imagination. The “black sacred cosmos or the religious worldview of African Americans” saw the whole universe was sacred.

Mika Edmondson

Lecrae Moore

And acknowledging the spirit world and human limitation doesn’t require a surrender to anti-intellectualism. Look no further than the brilliant Black organizers and tacticians who orchestrated the Civil Rights Movement from church fellowship halls. Leaders like Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth strategically outwitted devious Birmingham commissioners and sheriffs, proving logic was neither scorned nor in short supply in Christian advocacy circles.

Great minds were at work, but those minds weren’t obstacles to a greater faith. Faith and logic weren’t in conflict. These believers employed both. They were at peace and even celebrated dependence on a higher power (Prov. 13:4; Col. 3:23; Heb. 13:16). Their faith was refuge from the hopelessness of the skeptics. They knew prayer and a song of worship could accomplish things a philosophical treatise could not.

This Black church tradition can still provide a model for how Christian orthodoxy and orthopraxy can help the church and a polarized nation overcome the toxic culture wars and move toward a greater faithfulness and civic pluralism. Our historic public witness can correct many of the erroneous approaches, attitudes, and practices much of American Christianity has fallen into in the public square today. The Black church has a word for this moment in the public square.

Justin Giboney is an ordained minister, an attorney, and the president of And Campaign, a Christian civic organization. He’s the author of the forthcoming book Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around: How the Black Church’s Public Witness Leads Us out of the Culture War.

Adapted from Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around by Justin Giboney. ©2025 by Justin Giboney. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press. www.ivpress.com.

Justin Giboney

Justin Giboney

Justin Giboney

Justin Giboney

Justin Giboney and Chris Butler

View All

Vikram Mukka

“It is very scary out there. … But the Holy Spirit reminds [me] that ‘for when I am weak, then I am strong.’”

Jayson Casper

The history of this small Shiite sect includes assassinations, persecution, and periods of adherence to pluralism.

The Bulletin

Mike Cosper, Clarissa Moll

Vance hopes his wife becomes a Christian, fighting continues in Nigeria, and Tucker Carlson interviews Nick Fuentes.

Excerpt

Justin Giboney

An excerpt from Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around on family history, gospel music, and the great Christian legacy of the Civil Rights Movement.

Rachel Ferguson

Daniel Darling calls believers to their political duty, no matter the chaos.

News

Harvest Prude

Faith organizations hope the Trump administration will reverse course after the announcement of a historically low refugee ceiling.

Analysis

Emmanuel Nwachukwu

One pastor decries government denials that militants are targeting Christians.

The Russell Moore Show

Russell takes a listener’s question about the Church body convicting each other in love without unnecessary division.

You can help Christianity Today uplift what is good, overcome what is evil, and heal what is broken by elevating the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

© 2025 Christianity Today – a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International. All rights reserved.

Seek the Kingdom.