By Shiv Parihar on November 4, 2025

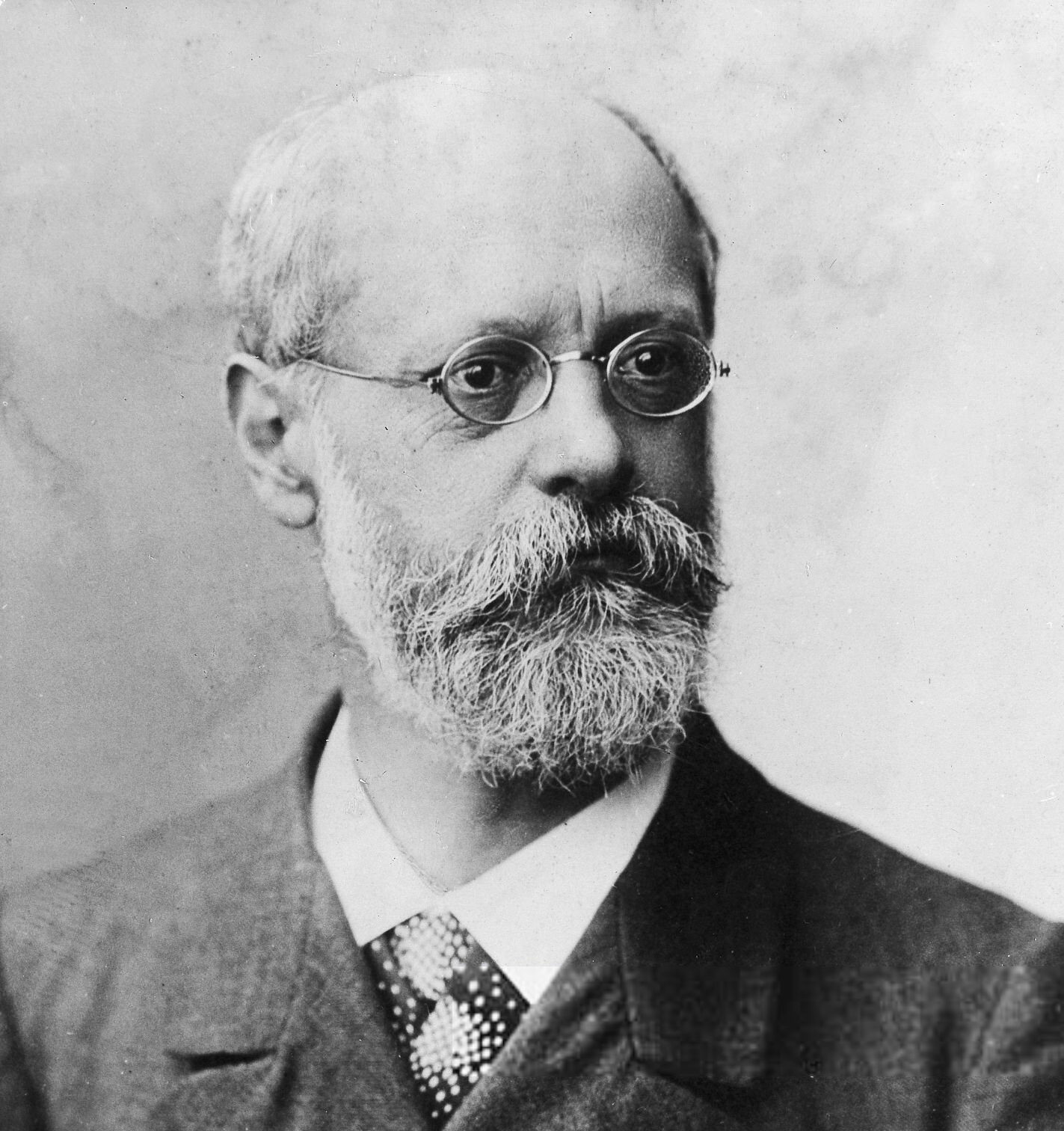

The interplay between Christianity and Marxism as a secular faith that tried (and failed) to supplant faith in Christ is well documented. Famously, it was a coterie of ex-communists that fired an opening literary salvo of the Cold War under the title The God that Failed, a theme carried forth by Whittaker Chambers, a Soviet agent turned devout Quaker, in his stellar memoir Witness. In the same vein, the German theorist Karl Kautsky (1854 – 1938) was known as the “Pope of Marxism” for his systematizing and popularizing of Karl Marx’s ideas. Kautsky influenced such figures as Vladimir Lenin in the Socialist International while he authored the programmes of the German Social Democratic Party, the largest socialist party in Europe in the lead up to WWI.

The global socialist movement turned their back on Kautsky, however, when he came to oppose his former Russian proteges’ Bolshevik revolution in 1917. Even so, Kautsky’s thought remained vital to future Marxist theoretical arguments and practical experiments. Central to Kautsky’s views was his historiography of Christianity, which he attempted to recast as a proletarian class struggle avant la lettre.

Kautsky first made this claim about Christianity in his Forerunners of Modern Socialism, published in volumes beginning in 1895, which he then further developed in Foundations of Christianity, published in German in 1908 and translated into English in 1915, the first full-length Marxist exposition of the Bible and Christian tradition.

Kautsky argued in Foundations that the history of Christianity was best explained as an example of dialectical materialism, the historiographical dogma at the core of Marxism, demonstrating that communism did not have to be imposed on the working class by intellectuals from above but could instead function as an organic and potent social force. Prominent contemporary Marxists such as Dan McClellan have described Foundations as “one of the most important Marxist contributions to the history of religion.”

Rather than attacking Christianity directly, Kautsky seeks to subvert and appropriate it, a more insidious endeavor. On the grounds that the narration was unreliable and that the Bible and other texts may have been altered, Kautsky makes the remarkable claim that “nothing definite about the life and doctrine of Christ,… [or] the social character, the ideals and aspirations of the primitive Christian congregation” can be known and thus, Christ, if he existed, is venerated only as a superb social organizer against colonialism. While this claim is obviously false, as even secular academics such as Bart Ehrman can attest, Kautsky makes other claims deserving of a response.

For instance, Kautsky dedicates roughly half the work to the “communistic form of organization” in Acts 2:44-45: “All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need.” These verses have long been difficult to grapple with. John Calvin faced his own class of radicals citing the passage, to whom he pointed out the exigence of the situation at hand and that “they [the Apostles] take away no other men’s goods.”

But the strongest retort may be from the 2nd-century Saint Irenaeus of Lyons. Commenting on this passage in Book IV of Against Heresies, Irenaeus wrote that “those who have received liberty set aside all their possessions for the Lord’s purposes, bestowing joyfully and freely not the less valuable portions of their property, since they have the hope of better things [hereafter]; as that poor widow acted who cast all her living into the treasury of God.” Kautsky interpreted Christianity as only socializing production, while Marxism built upon this foundation by socializing consumption as well. Irenaeus, however, exposes the fundamental myopia of Kautsky’s analysis: his inability to comprehend the spiritual, immaterial impulses that propelled Christianity from a minority sect to the largest religion in the world. The Apostles and their disciples abandoned material possessions out of a deep faith in the Kingdom of God beyond this world, not out of the “fierce class hatred” Kautsky attempts to project onto the early Church.

For Kautsky, the very conception of a crucified God who would die for no material purpose is inconceivable. Even from a secular perspective, he simply cannot take seriously the idea that people across ethnic and class lines would unite to struggle for their faith in a God they believed had died on the cross for a New Covenant in which they were included. Thus, Kautsky must grasp at straws to claim Christ, if he did exist, as a proto-communist “who was crucified for his unsuccessful uprising,” a fact he suggests was covered up as the Church gradually lost its character as a revolutionary organization by way of bourgeois infiltration.

Kautsky’s fault brings one back to his intellectual father, Karl Marx. Marx began his career as a Young Hegelian, a fact often repeated today without adequate context. The split between those now known as the Old/Right Hegelians and the Young/Left Hegelians grew from the publication of David Strauss’s Life of Jesusin 1835. Old Hegelians, almost all students of G.W.F. Hegel himself, believed deeply in Christianity and of the triune God as the chief player in world history. In contrast, the “Young” Hegelians such as Strauss and Marx, used Hegel’s system to reject Christianity, beginning with Strauss’s work of liberal theology that reduced Christ to a mere charismatic preacher. Kautsky’s work crosses the Rubicon of denying the historical Jesus, a position now overwhelmingly rejected by scholars.

Broadly, nonetheless, he builds upon the same themes as predecessors such as Strauss, adding pieces such as a breakdown of the Sadducees as aristocrats, Pharisees as a bourgeois “Third Estate,” and Essenes and early Christians as proletarians. This analytical lens is robbed of its worth by the militancy of the author’s anti-Christian agenda.

Kautsky accounts for the spread of Christianity by claiming that “neither the Roman law nor classic literature could please the proletariat and its sympathizers…the traditional communism of primitive Christianity was well suited to their own necessities.” The thesis that the turn of Romans to Christianity was a material turn away from the problems of pagan society has spread far beyond Kautsky. In short, Kautsky and his followers ignore the evidence to the contrary, such as the Roman military officer St. George or the high-born and elite-educated St. Justin Martyr, executed under Diocletian and Marcus Aurelius, respectively. Indeed, even if we somehow supposed that Kautsky were correct about the first years of Christianity, he provides no cogent explanation for why the Church of Polycarp, Irenaeus, and Origen, clearly bereft of class hatred, would have spread as it did.

Kautsky’s version of Christianity is itself a God that failed. It begins as a movement of proletarian revolutionaries and before transforming into a form of the very oppression it was formed to destroy. The irony of Kautsky’s own story turns his book on its head when read from today. Karl Kautsky was wrong about Christianity, but his analysis, shifted to Marxism itself, rings true. A movement began in the clothing of liberation of the masses produced a totalitarian system unlike any man had ever known. Karl Kautsky would live to see his one-time followers murder millions. His history of Christianity missed its target in the Church, but in the process it inadvertently told the far more disturbing story that was to come in the decades of communist tyranny soon to unfold.

Shiv Parihar is a writer and political activist from Utah. Parihar has contributed to publications including The Salt Lake Tribune and writes the newsletter A New Frontier. He is currently studying politics and religion at Claremont McKenna College.

Providence is the only publication devoted to Christian Realism in American foreign policy and is primarily funded by donors who generously help keep our magazine running. If you would care to make a donation it would be highly appreciated to help Providence in advancing the Christian realist perspective in 2025. Thank you!

Events & Weekly Newsletter Sign-up

Sponsor a Student for Christianity & National Security!

Providence‘s biggest event of the year, the Christianity & National Security, will take place over Oct 16-17 in Washington, DC, for undergrad and grad students. It costs $500 per student to make this event happen. Please support Providence as the premier voice of Christian Realism in America! Any amount helps.

Related articles

Tim Milosch

October 16, 2025

Lauren Knights

October 10, 2025

Miles Smith

September 25, 2025

Mark J. Larson

September 9, 2025

Paul Marshall

May 1, 2025

Receive expert analysis in your inbox.

Institute on Religion and Democracy

1023 15th Street NW, Suite 200

Washington, DC 20005

Visit

Connect

© 2025 The Institute on Religion and Democracy. All rights reserved.