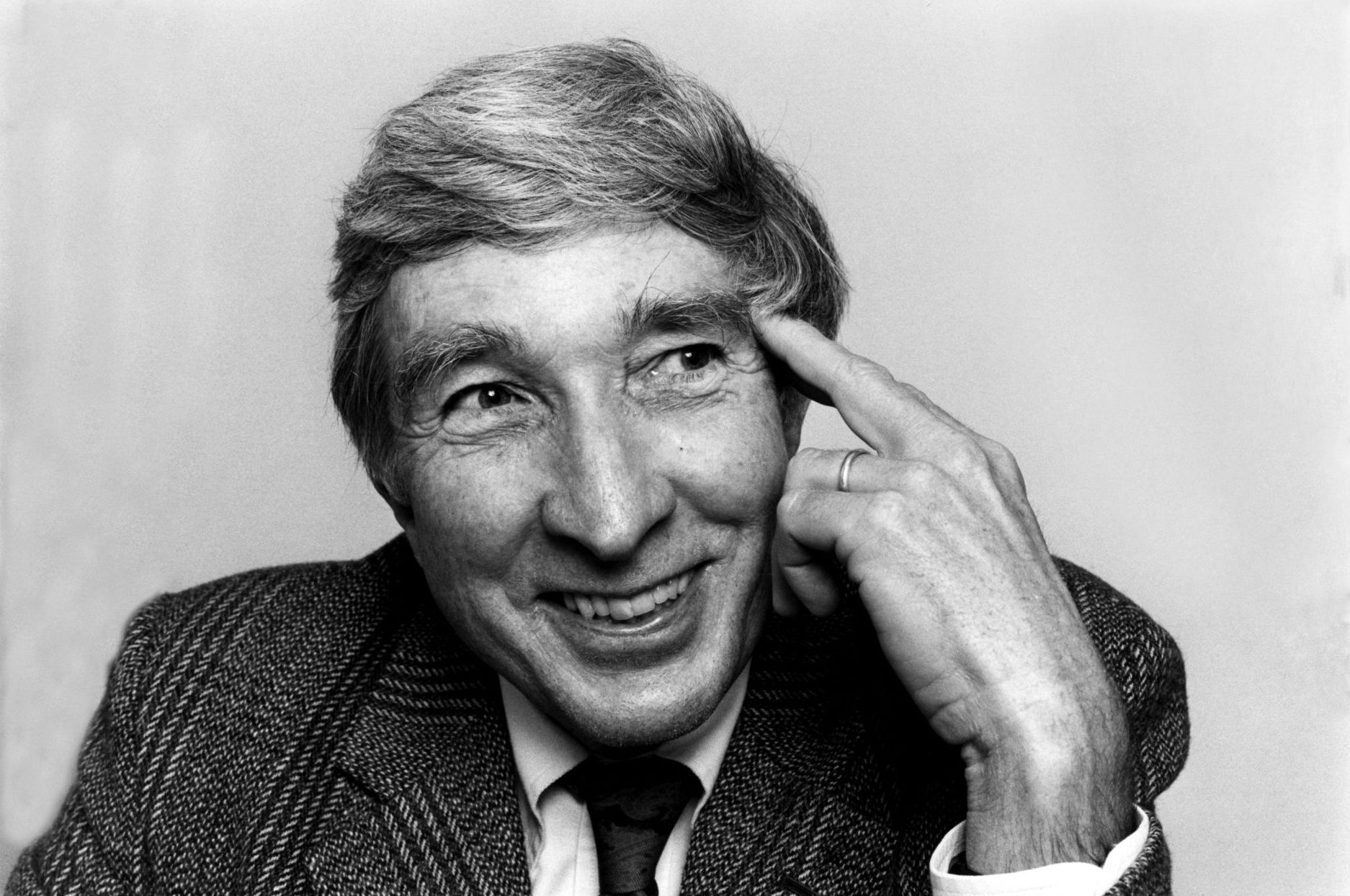

’Updike was, for all his libidinous reputation, a surprisingly serious fellow.’ Credit: Ulf Andersen / Getty Images

’Updike was, for all his libidinous reputation, a surprisingly serious fellow.’ Credit: Ulf Andersen / Getty Images

John Updike was not so much a “penis with a thesaurus”, as he was once described, as a penis with a theology. His parish was the marital bed; his liturgy, the orgasm. His grand subject was, of course, sex. Yet his inordinate fascination with its mechanics was accompanied by a loftier metaphysical obsession. Simply put, Updike spent a lifetime trying to reconcile promiscuity with Christianity.

Over 60 volumes, each approaching this idée fixe from a slightly different angle, attest to that monomaniacal pursuit. The same preoccupation animates his correspondence — some 25,000 letters, a slender selection of which is due to appear next week as A Life in Letters, edited by the Cincinnati don James Schiff. Here, as in his fiction, the erotic and the ecclesiastical intertwine, rendering his theology of tumescence in full relief. By turns fascinating, embarrassing, and even moving, the letters reveal that Updike’s ceaseless coupling was never quite about lust at all. It was about faith — about locating meaning amid the mundanities of the modern world. Though he merely flits through these pages, the presiding spirit of this collection is the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, one of Updike’s heroes, whose theology equipped him with a worldview.

Updike was, for all his libidinous reputation, a surprisingly serious fellow; and the fact that so little scholarly or journalistic ink has been spilled on this unexpected influence is testament to how precipitously his star has fallen in our century. He is now read, if at all, as a period curiosity. In a letter to Ian McEwan in 2005, he saw it coming: “It occurs to me that since you interviewed me that first time in a BBC studio you have risen to be generally called the best novelist of your generation whereas I have fallen to the status of an elderly duffer whose tales of suburban American sex are hopelessly yawnworthy period pieces.”

He was right. Updike has been superseded by events. His tales of New England adultery, those lovingly lacquered chronicles of cocktail parties and postprandial assignations, now have the texture of foxed antimacassars. What enormous strides we have made since Couples, which surveyed the lives of wife- and breastmilk-swapping swingers in suburbia, became a succès de scandale in 1968. At the start of that decade, he feared imprisonment for the indecencies of Rabbit, Run; now, in the age of gooning, it is hard to imagine the average teenager feeling so much as a smutty frisson reading Updike.

Then there have been the belated stabs at outright cancellation. Patricia Lockwood, in a takedown calibrated to appeal to the pustular trust-fund babies of Brooklyn and Brixton garrets who howl “problematic” with dispiriting frequency, likened his prose to “a malfunctioning sex robot attempting to administer cunnilingus to his typewriter”. The charge is familiar: that his femmes fatales are fantasy projections, his patriotism tedious; that he mistook vaginal depth for his own. And there is truth in it. He could never quite portray women — only paint them, in glossy, adulatory strokes, as creatures of allure.

Nor do his politics endear him to contemporary sensibilities. Updike was a reactionary Democrat, given to taking pot-shots at the civil rights movement. More egregiously, he was a cheerleader of the Vietnam War. Finding himself, awkwardly, in a minority of one as the only prominent American novelist “unequivocally for” the war, he attempted a feeble course correction that was at once defensive and disingenuous: “How could anyone not be at least equivocal about an action so costly, so cruel in its details, so indecisive in its results? The bombing of the North seems futile as well as brutal and should be stopped… I differ, perhaps, from my unanimously doveish confrères in crediting the Johnson Administration with good faith and some good sense.”

Such views scream suburban parochialism, of which he was a product. Born in 1932 in Shillington, Pennsylvania to Lutheran parents, Updike grew up in a world of scripture and Sunday school. Aged 13, however, he moved to his maternal family’s farm in Plowville: “Never since leaving it,” he later wistfully wrote, “have I enjoyed such thrilling idleness.” Later came Harvard, followed by a year at Oxford’s Ruskin School and then a position as a staff writer at the New Yorker. There, he developed a lifelong allergy to what he called the “elegant hacks” of literary Manhattan. In 1957, aged 25, he decamped with his wife and two children to Ipswich, Massachusetts (the real Tarbox of Couples), a move he justified as parental prudence, but one suspects small-town anti-intellectualism had rather more to do with it. He would never return.

His great creation Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a Pennsylvanian without a degree, embodies this stubborn provincialism. Like in Updike himself, there’s something of the autodidact in Rabbit’s steady accretion of a menagerie of lovers. These were not the one-night assignations of the skirt-chaser. Rabbit, rather, was trying to find existential meaning through concupiscence, to transcend the vapidity of postwar American life.

By Sarah Ditum

As in Updike’s fiction, so in his letters. The Ariadne’s thread here, inevitably, is Updike’s sexual excursions and their ramifications. For a man so routinely portrayed as America’s priapic laureate, his body count — 13 — feels almost monastic. Then again, he was a late starter. His first marriage, to Mary Pennington, a Unitarian minister’s daughter, began with virginal vows. “I am very interested in sex,” he had admitted to her in 1952, before conceding his knowledge of it was chiefly theoretical.

Then there is the “adulterous affair”, as Schiff fustily puts it in his footnotes, with Joyce Harrington (“the life of the party”) in 1961-62, later written up as Marry Me, a work that, were Updike a fortysomething woman today, would pass for autofiction. Two years later came Joan Cudhea: “You are visually charming,” he wrote to her, before dispensing with the gallantry and thanking her “for your goodness, your shyness, your eyes, your tongue, your glimpsey ass, your yummy cunt”.

By 1974, his marriage had taken a desultory turn. Martha Bernhard — his neighbour, who studied under Nabokov at Cornell and later became Updike’s wife — rekindled his joie de vivre. On the eve of their marriage, he confessed to a ménage à trois with two Australian women (“awful of me”). Apart from this drip-feed of revelations, Martha also had to fend off literal blows from Mary: “you knocked her down as a mechanic would wipe a piece of grit out of a balky machine,” Updike wrote of a catfight.

These letters double as field notes from the sexual revolution. Updike, it seems, recognised them as such, repurposing them in his fiction. “Driving back from taking the babysitter home,” goes a line in one typical story, “Frank would pass darkened houses where husbands he knew were lying in bed, head to murmuring head, with wives he coveted.” Perhaps he was thinking of Martha, who was married to a clerk when she started seeing Updike. In another story, he surely had Joan in mind when he wrote: “Ever since my days of car-seat courtship I’ve liked to press my face into a girlfriend’s nether soul, to taste the waters in which we all must swim out to the light.”

Yes, the prose can be overwrought, the sex inadvertently comic. Updike’s sentences luxuriate perhaps a little too much in particulars. For some, this is style without substance. “Updike has nothing to say,” declared the literary critic John Aldridge. But he does. Behind the bustle and bumping, one senses the spectre of Søren Kierkegaard, whose book Fear and Trembling features among Updike’s favourite books, listed in a 2005 letter to his Knopf publicist. Four decades earlier, in 1965, Updike wrote an entry on Kierkegaard for a compendium of biographical sketches. In a 1974 letter to Mary, he remarked that life in Ipswich was “very depressing, but for the Kierkegaard”. At one point, he even admitted that “for a time, I thought of all my fictions as illustrations of Kierkegaard”.

Like Kierkegaard, Updike prized interiority: inwardness and individuality were what mattered, not collectives or society. From the Dane, the American learned that desire ought not to be condemned but redeemed. This is the crux of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, which sets out two lifestyles — the aesthetic and the ethical. Love and sex belong to the former, a realm of sybaritic hedonism that can, through acts of faith, be transfigured into the latter. This is Kierkegaard’s fideism; faith is placed above reason and passion before proof.

By Pratinav Anil

Updike’s strategy is much the same. In Couples, as in the Rabbit novels, sexual desire is not denied (far from it) but elevated into a quasi-religious register, made almost an article of faith. His aim is to render the ordinary radiant — to “give the mundane its beautiful due”, as he put it. Writing to his publisher Victor Gollancz in 1960, Updike explained that sex was, in his fiction, merely a springboard for reflection on “the innerness that nourishes Christian orthodoxy”.

So far so Kierkegaardian. Yet there is, all the same, a distinctly American inflection to Updike’s Kierkegaardianism, as David Crowe observes in his rather desiccated but valuable study Cosmic Defiance — still the only sustained treatment of this intellectual lineage. Crowe notes, rightly, that Updike’s characters rarely complete the Kierkegaardian ascent from aesthetic indulgence through ethical responsibility to purblind faith. They quail at the leap, lingering instead at the threshold. To my mind, this is to Updike’s credit. There is no preachiness in his pages, no hortatory insistence that we discern the piety beneath the prurience, the hymn beneath the hard-on. The irresolution is precisely what makes his heroes human.

Pratinav Anil is the author of two bleak assessments of 20th-century Indian history. He teaches at St Edmund Hall, Oxford.

We welcome applications to contribute to UnHerd – please fill out the form below including examples of your previously published work.

Please click here to submit your pitch.

Please click here to view our media pack for more information on advertising and partnership opportunities with UnHerd.