Advancing the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Evangelical scholar Yoichi Yamaguchi shares how Shinto influenced the development of emperor worship and the ways Christians responded.

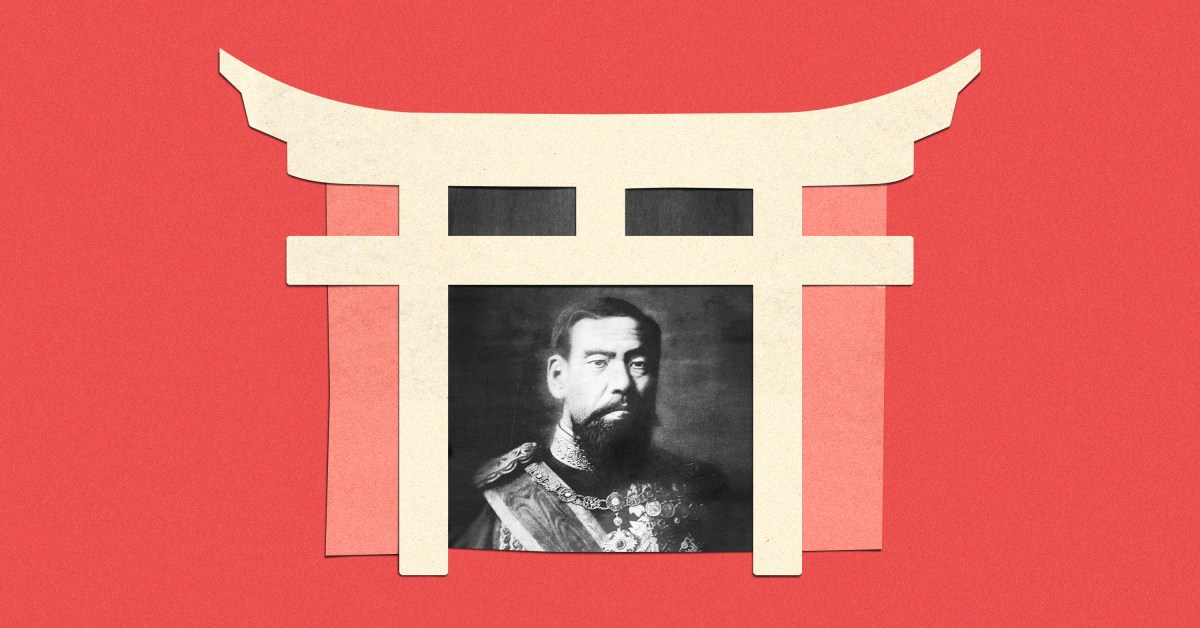

A portrait of Emperor Meiji.

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Christianity Today interviews Yoichi Yamaguchi, director of the International Mission Center at Tokyo Christian University, about Shinto’s long-lasting significance in Japan and how early believers responded to the imposition of emperor worship.

Can Shinto be considered Japan’s national religion?

While the Japanese imperial household conducts official Shinto rituals using the state budget today, Shinto was never officially declared the national religion in the country.

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for signing up.

Explore more newsletters—don’t forget to start your free 60-day trial of CT to get full access to all articles in every newsletter.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Japanese officials wrestled with whether Shinto could be declared a religion. Progressive bureaucrats who sought globalization firmly opposed using the term state religion, unlike conservative court officials seeking to preserve Japanese traditions.

During the drafting of Article 28—the clause on religious freedom—in the Meiji Constitution established in 1889, Japanese conservatives proposed to qualify religious liberty with the condition that it would not contravene the national religion. Their proposals were ultimately rejected, and the final constitution did not contain the term national religion at all.

Nevertheless, Shinto operated as a de facto national religion to strengthen national unity.

What about State Shinto? How and why was that established in Japan? How did Christians at the time respond to it?

While the Meiji government upheld a façade of religious neutrality, it established a system in which State Shinto, where people revered the emperor as a supreme being in Japan, occupied a central role in civic life.

The emperor was perceived as a semidivine figure who was a descendant of the sun god Amaterasu, and people believed he could be a mediator between deities (kami) and humans.

The Imperial Rescript on Education, a key ideological document of the Meiji state published in 1890, reflected how influential and pervasive Shinto was in society. Written by government officials and issued by the emperor, the rescript embodied the values of an emperor-centered state cult as a guiding principle for all spheres of education. Japanese people at the time treated the rescript as a sacred text because they thought the emperor, as a supreme being, had absolute authority.

In 1891, one notable conflict between Christianity and state ideology emerged in what is known as the “disrespect incident.” Kanzo Uchimura, a prominent Christian leader and public school teacher, was censured for refusing to bow to the document containing the rescript.

Over time, however, both state and church leaders came to insist that Christianity and State Shinto were not in conflict and could coexist. From 1930, the Japanese government began asserting that Shinto and imperial worship were only expressions of Japanese culture and identity rather than religious acts that conflicted with Christian beliefs.

This view slowly gained traction among the majority of Christian leaders, who thought it would make evangelism easier.

What elements of Shinto exist in contemporary Japan?

Until recently, Japan’s national broadcasting station, NHK, aired a Saturday-morning radio program called Good Luck Shrine Walks (Ayakari Jinja Sanpo), which featured shrines that are reputed to bestow good fortune.

In many Japanese companies, employees are often expected to visit a shrine together on New Year’s Day to pray for the organization’s prosperity. Companies also often maintain a household shrine (kamidana) in their offices for good luck. These practices are considered not religious but merely cultural by most Japanese.

Traditional Japanese festivals such as children’s fairs (omatsuri) are also held in shrines, although these practices have been decreasing in recent years.

Learn more about Shinto’s key teachings, the ways Christianity and Shinto interacted in Japan, and missions and evangelism in a Shinto-influenced culture.

Kazusa Okaya

Martin Heisswolf

Tony Chuang

Nori Kanashiro and Isabel Ong

Samuel Lee

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

Interview by Kazusa Okaya

View All

Divya Chirayath

For many couples, in-laws are a major source of marital strife.

The Bulletin

Mike Cosper, Clarissa Moll, Russell Moore

Trump hints at running in 2028, US strikes more alleged drug boats, ChatGPT produces erotica.

Review

Perry L. Glanzer

A new account of faith in higher education adds some neglected themes to more familiar story lines.

Daniel Silliman

In 1958, CT pushed evangelicals to engage important moral issues even when they seemed old-fashioned.

Interview by Haleluya Hadero

The head of The T.D. Jakes foundation on job assistance and economic empowerment.

The Just Life with Benjamin Watson

Unpacking the crisis facing Nigeria’s persecuted Church

Eric McLaughlin

Scripture speaks of death as an enemy Christ conquers—and the door through which we see God face to face.

Review

J. Alan Branch

A new book acknowledges both categories as biblically valid—but insists on ordering them properly.

You can help Christianity Today uplift what is good, overcome what is evil, and heal what is broken by elevating the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

© 2025 Christianity Today – a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International. All rights reserved.

Seek the Kingdom.