Save 50% through 12/1. Join Now

Advancing the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

Chris Butler

Contributor

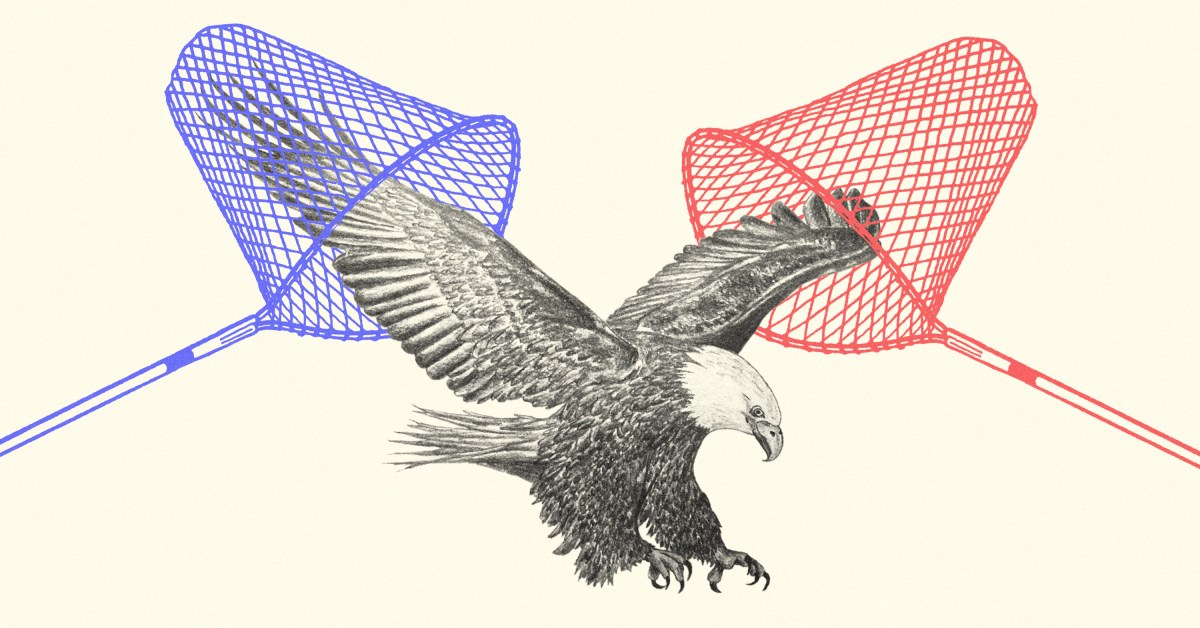

Both parties are enmeshed in an ongoing identity crisis. The chaos can give us a chance to rediscover what we’ve lost.

I grew up in the front row of the church and on the frontlines of Chicago politics.

My view of public life was formed in church basements, union halls, and on the front porches of red-brick bungalows lined up on the west side of the city. As a kid, my great-aunt Irene worked as a precinct captain, mobilizing voters for Democrats, while my cousin brought neighborhoods together to address local issues.

On Saturday mornings, I often saw a generation of seasoned Black organizers gather at an advocacy organization to sing rapturous Gospel music, listen to a sermon, and then pour out to register, educate, and mobilize voters. The job wasn’t merely to win elections but also to protect the dignity of our people.

Get the most recent headlines and stories from Christianity Today delivered to your inbox daily.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for signing up.

Explore more newsletters—don’t forget to start your free 60-day trial of CT to get full access to all articles in every newsletter.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

At the time, the distance between my parents’ pews and my community’s politics wasn’t far—similar people and values, just different platforms of expression. Even inside the world of partisan politics, which I pursued as a calling later in life, I saw myself as a part of something separate and distinct. Over the years, however, that distinctiveness seemed to fade.

We’re currently living through a strange and volatile political time that could be an invitation for rediscovery—not only for the Black church but also for evangelicals across the board.

On one side, the Democratic Party is in the middle of a very public identity crisis. The same night that New York City’s Zohran Mamdani, a democratic socialist, was elected mayor—with a mandate to push left-wing policies from public grocery stores to rent control—Virginians delivered a decisive win to Abigail Spanberger, a moderate who represents a very different vision for the party.

Meanwhile, Democratic leaders like governors Gavin Newsom and J. B. Pritzker and former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel are all positioning themselves as presidential hopefuls, each offering distinct styles for the party’s future: technocratic management, progressive populism, or pragmatic machine-style politics.

Republicans, for their part, are in no less turmoil. Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene recently announced she was resigning from her position after a high-profile fallout with President Donald Trump on a host of issues, including the Epstein files.

Separately, Tucker Carlson’s friendly interview with a white nationalist and avowedly racist antisemite ignited bitter infighting among conservatives, which, as commentator Jonah Goldberg recently told Vox, is “previewing the bigger wars to come about what the right is about, who can be tolerated as part of the coalition, and who can’t be.”

In short, both parties are drifting, while the coalitions that once held them together appear to be fracturing in real time. Some of the attempted realignment is symptomatic of the moral rot in our politics. As the parties are trying to discover who they are, however, it can also offer the American church an opportunity to retrieve our own identity independent of the political chaos.

Harvest Prude

Russell Moore

Three years ago, I ran for Congress as a pro-life Democrat. When I look back on it now, that was the moment the need for political renewal felt undeniable to me. Friends—even those who were Christians—withdrew, and former colleagues insisted I should “just be a Republican” because of my pro-life views.

Perhaps most painfully, many Black churches—whose pews had taught me a moral vocabulary of responsibility, family formation, and the sacred worth of children—lined up to support candidates who had discarded those values entirely.

This took place in the aftermath of the Democratic Party’s shedding of pro-life voices across the board. In 2010, for example, the party had around 40 national legislators who held pro-life views, according to New York Times writer Ezra Klein. Today, there’s virtually none. The Republican party has also backed away from its strong pro-life stance while the Black church, a traditionally Democratic voting bloc, has all but lost its distinctive voice on the issue.

That’s not the only thing that has been lost. Many have strayed from talking about economic justice with a healthy respect for personal responsibility or a high view of the traditional family structure, while still defending the dignity of those who don’t belong to one. We rightly agonize over how to make our criminal justice system fair and equitable. But we can’t seem to do that while still holding fast to the belief that those who commit crimes should be held responsible for the harms inflicted on communities.

While all this is happening, the Black church has also been losing political power. Young people are leaving and are increasingly becoming discipled by the liturgies of secular progressivism or the moral intuitions of secular conservatives. They are also being drawn to other traditions or to alternative spiritual movements—places where belief feels less superficial and the bar for belonging and participation feels higher.

When churches become little more than cultural outposts for partisan ideology, rather than the kind of spiritual communities that shape political judgment through Scripture, tradition, and discipleship, they cease to offer a compelling reason for continued participation.

The problem is not that Black churches, or any churches, lack moral convictions. It’s that we often express those convictions in the language of the parties rather than the language of the faith. We trade our prophetic distance for proximity to power and forget that our social authority arose from our willingness to be different.

Daniel K. Williams

Justin Giboney

Whether they admit it or not, both parties need religious Americans to succeed. An identity crisis gives the church an opportunity to make a demand on them—not as beggars seeking concessions but as citizens with the right to negotiate the moral terms of this country’s political future. I’m not saying we can ultimately control what Democrats or Republicans become. We can’t. But when we remember who we are and act accordingly, our voice can carry further than we know.

This is where the history of the Black church has something crucial to offer. I say this not because it is the only Christian tradition worth analyzing, but because its historical political witness avoided the great temptations of cultural assimilation and retreat. At its best, the Black church offered something our politics rarely produces: compassion with conviction, justice rooted in righteousness, hope grounded in sacrifice, and resistance joined to reconciliation.

If the church hopes to speak with moral clarity into this political vacuum, we must learn again what the Black church once embodied.

The first thing to remember is that distinctiveness matters. The Black church held moral authority because its theology shaped its politics, not the other way around. It critiqued exploitation from the right and overreach from the left. It refused to treat the individual as an autonomous unit unconstrained by community, just as it refused to treat the community as a collective that bears no responsibility for individual decisions and actions.

At a time when both parties are fostering a culture that undercuts the biblical view of the imago Dei—whether through identity idolatry or hyper-individualistic autonomy—the church must recover its own distinctive vision of human dignity.

Secondly, we can maintain proximity to people who face disadvantages without being captured by partisans. The Black church was able to stand close to victims of housing injustice, health disparities, and other types of disenfranchisements without merely mimicking those offering plausible policy solutions. We need that kind of posture today to correctly address challenges faced by African Americans, working-class white communities, and immigrant populations navigating an upheaval in policy and enforcement.

Thirdly, we must remember that the church’s most powerful political act is in shaping voters, not in mobilizing turnout. We are called to disciple people by helping them think biblically about life, weigh tradeoffs, seek the common good, and discern justice. Election decisions matter, but we can’t treat them as substitutes for good discipleship.

Lastly, courage can be exhibited without belligerence. The current political atmosphere rewards outrage, while tribes treat disagreement as betrayal. But believers who know their identity in Christ can model the courage to speak without cruelty, challenge without demeaning, and confront without dehumanizing.

We don’t do this for civility’s sake but because it’s what Jesus demands of us. After all, we have not been called to be witnesses to the aspirations and anxieties of the left or the right, but to the kingdom of God breaking into the world. If we fail to do that, our moral authority will continue to erode, slowly at first (as it already has), and then all at once.

Chris Butler is a pastor in Chicago and the director of Christian civic formation at the Center for Christianity & Public Life. He is also the co-author of Compassion & Conviction: The And Campaign’s Guide to Faithful Civic Engagement.

Chris Butler

Chris Butler

Justin Giboney

Justin Giboney

Russell Moore

View All

Elisabeth Kincaid

Beth Felker Jones’s book charitably holds up its merits against other traditions.

Joshua Bocanegra

Following Jesus doesn’t require rejecting my family’s culture. God loves my latinidad.

News

Jill Nelson

With media-influenced young evangelicals wavering, Jerusalem seeks a counter.

The Bulletin

Clarissa Moll

Walter Kim and Nicole Martin discuss the continuing evangelical mission of CT.

Interview by Ashley Hales

A conversation with pastor and author, Nicholas McDonald, about Christian witness in a cynical age.

Paul Marchbanks

In “Wicked: For Good,” the citizens of Oz would rather scapegoat someone else than reckon with their own moral failings.

O. Alan Noble

Gratitude is more about action than feeling.

Wire Story

Yonat Shimron in Coleshill, England – Religion News Service

After years of planning and fundraising, the roadside landmark shaped like a Möbius loop will represent a million Christian petitions, brick by brick.

You can help Christianity Today uplift what is good, overcome what is evil, and heal what is broken by elevating the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

© 2025 Christianity Today – a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International. All rights reserved.

Seek the Kingdom.