The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

This fall in Copenhagen, I walked in the early morning through quiet streets, past closed shops. I was looking for the Church of Our Lady, the Neoclassical cathedral of the Lutheran church in Denmark. Unlike so many other European cathedrals, this church radiates light when you step in from the narrow, darkened streets. Surrounded by statues of the apostles, when you stride down the center aisle toward Jesus behind the altar with his arms stretched down in invitation, the lanterns beckon, Post tenebras lux. After darkness, the light of the Word shone again with the Protestant Reformation.

Not long after opening, I entered the cathedral with a second visitor. Toward the front, I found a third. Tour enough European churches and you expect to find a smattering of older women at prayer. Not this time. The two other visitors were young men, native Danes, reading and praying.

I visited the morning after the Charlie Kirk memorial service back in the United States. All week, leaders and guests at our TGC Norden conference wanted to ask me about Kirk. The stadium-size worship service, complete with gospel preaching from a high-ranking politician, would be unthinkable in Scandinavia, one of the world’s most secular regions. But church leaders from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and the Faroe Islands told me they’ve been seeing a little of what I saw in the Church of Our Lady: increased receptiveness to the gospel from young men.

As I walked back to my hotel and prepared to catch my flight, I pondered what it means to live in a post-Christendom world, as explored in The Gospel Coalition’s new book, The Gospel After Christendom. Maybe we’re not as secular as I thought, at least in the United States. Maybe the fusion of Christian witness and political power remains stronger than declining church attendance would suggest.

Mulling these thoughts on an enjoyably cool morning just outside the cathedral, near the University of Copenhagen, I noticed a pride flag. Then another. Then another. I’d stumbled into a gay-bar district on my way past the train station to my hotel next to a strip club. And I began to understand more of our predicament in the post-Christendom West. One group may show encouraging interest in the gospel while another runs far away from God. One country can experience revival while churches empty in another. Social media shows one group a martyr while another group sees red.

Charles Taylor famously began his definitive account of secularism by describing the loss of religious assumptions between 1500 and 2000. In Luther’s day, you had to opt out of religion. In our day, you must opt in. Faith is contested by the pluralism of our eyes. Everyone knows you don’t need to be Christian, that Christians don’t hold a monopoly on power. That’s our post-Christendom world, where belief sprouts on one street and decadence rules on another.

Secularization Thesis

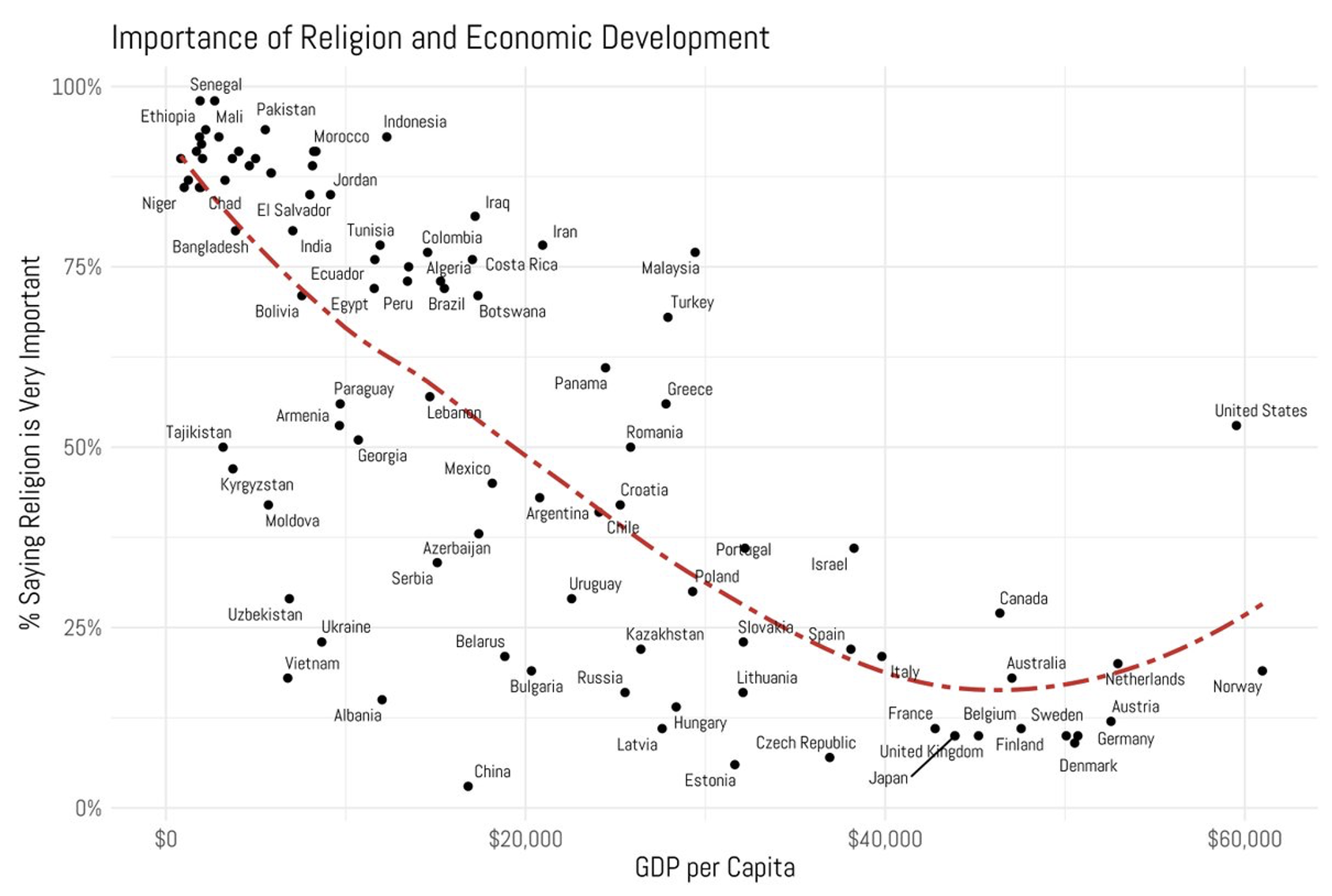

Earlier this year, a friend asked me to explain the differences between the United States and Europe, especially when it comes to religion and secularism. I spent sleepless nights in Copenhagen thinking about this question. The social scientist Ryan Burge is always good with graphs that illustrate these dynamics. He showed that the richer the country, the lower the religiosity.

In Luther’s day you had to opt out of religion. In our day, you must opt in.

In Luther’s day you had to opt out of religion. In our day, you must opt in.

This is the standard secularization thesis. Make money, lose God. Norway is the richest nation in the world, according to GDP per capita. Just ahead of the United States. Less than 20 percent of Norwegians say religion is very important. Denmark, Sweden, and Finland are even lower.

But there’s always been one big outlier to the secularization thesis. That’s the United States, where 52 percent of Americans say religion is important.

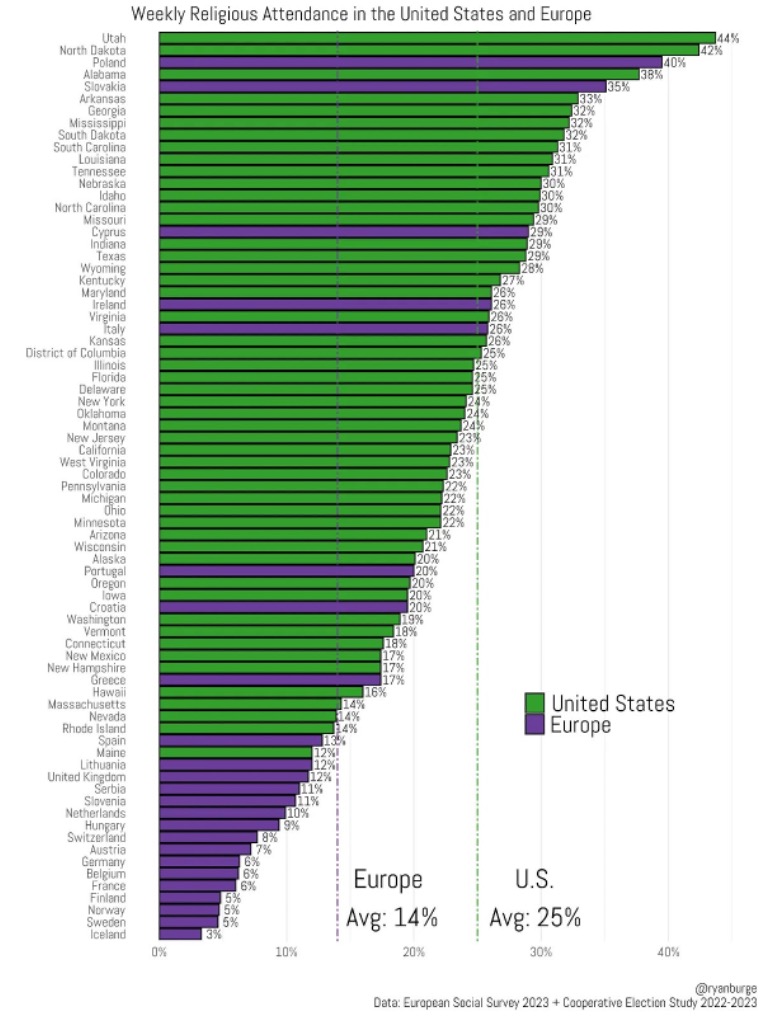

But this chart isn’t my favorite from Burge. The United States is big and diverse. So is Europe. Some European countries look more like the United States. Some states look more like European countries. If we’re really going to get to the bottom of the differences in religiosity and secularism, we need to look deeper.

Overall, 25 percent of the U.S. population attends a religious service weekly. That number is 14 percent for Europe. It’s no surprise to see Mormon Utah and Lutheran North Dakota top the list. But #3 and #5 are two post-Communist Eastern Bloc states, Poland and Slovakia. We’ll return to explore the significance of these two countries.

Then a host of states follow, including Arkansas and South Dakota, until you get to a few European countries, notably Ireland and Italy, around the national U.S. average of 26 percent weekly attendance. Most of Europe clusters around the bottom of the list, from 13 percent weekly church attendance in Spain and 12 percent in the United Kingdom, all the way down to 3 percent in Iceland.

You’ll see on this list, however, that several U.S. states are just as secular as many European countries. Only 14 percent in Massachusetts attend church weekly. It’s 12 percent in Maine, the most secular state. Vermont is 18 percent, the same as Connecticut. New Hampshire is 17 percent. It’s not that all of Europe is secular. Poland and Slovakia feel like the American Bible Belt. And it’s not that the United States is religious. New England belongs in Scandinavia. No wonder so many Americans from the South struggle in ministry when they move to New England. They might as well be in Norway.

Visiting Copenhagen for the third time, I got a feel for the challenges of secularism as I talked to pastors and missionaries—some native Nordics, others from the United Kingdom, and many from the United States. I tried to listen and watch, observe and take notes.

The first night that I taught from Jeremiah for TGC Norden, F.C. Copenhagen was playing a Champions League match against Leverkusen from Germany. I could have walked to the stadium from the church in less than 40 minutes. Needless to say, my preaching was no match for football’s draw. Like in the United States, sport has increased as religion has decreased as the object of devotion, time, attention, and money.

Then, on Saturday morning, I wandered the clean, safe streets as crowds enjoyed coffee and pastries in unhurried sidewalk cafes. Laughing children danced in the fountains of the town squares. I arrived at the church just in time to hear my friend Christian Roth close the conference by preaching an excellent message on suffering from Romans 8.

The transition from the sunny streets to the stuffy church jarred me. And I asked myself, Which one of us is out of touch with reality? Of course, it’s the crowds in the streets, showing far less concern for the inevitability of death than their existentialist ancestor Søren Kierkegaard (buried not far away from the church) thought they should.

Then I asked myself, But who feels out of touch with reality? We do, the Christians sitting inside a dark church talking about suffering and the sovereignty of God. We’re the ones who feel like we’re living a self-inflicted nightmare while the world enjoys the last weeks of sun before the long northern winter descends with its early nights and late mornings.

These church planters and missionaries are my heroes. They’re pillars of reality and truth amid the unreality of abundance you can’t take with you into eternity. They face apathy and sometimes outright opposition from people amusing themselves to death with alcohol and drugs.

This is the challenge of Christianity in our secular age. It’s not that we’re wrong. Changing cultures don’t change the fact that 2,000 years ago, Jesus the Son of God rose from the dead, and he’s the only way any of us can escape the sentence of death and eternal judgment. The challenge is that in many secular places, belief in Jesus doesn’t feel needed. He doesn’t feel necessary for doing good or living a good life. It’s the same story from Boston to Manchester, Bergen to Malmö. Reality doesn’t feel real.

Cracks in the Secularization Thesis: Two Clues

If we’re going to crack the missional problem of secularism, we need to look at the differences between the United States and Europe, and that means we need to look closer at the differences between different countries in Europe and different states in the United States.

1. Catholics fare better overall than Protestants.

The first thing you see is a clear Protestant/Catholic divide. Poland, Slovakia, Ireland, and Italy are all predominantly Catholic countries. Norway, Sweden, and Iceland at the bottom are historically Protestant countries. So we have our first big clue, that there’s something different between Protestants and Catholics, at least when it comes to weekly church attendance and saying religion is very important.

This is the challenge of Christianity in our secular age. It’s not that we’re wrong. It’s that Jesus doesn’t feel needed.

This is the challenge of Christianity in our secular age. It’s not that we’re wrong. It’s that Jesus doesn’t feel needed.

When you look at the United States, the picture doesn’t look so clear, at least at first. Predominantly Protestant states in the Deep South, with high concentrations of Baptists and Methodists, rank highest. The mostly Catholic states of New England rank lowest. Does that mean, then, we can’t derive any insight from this distinction?

I still think we can, and here’s why. What do we see in common between the most religious European countries and the most religious American states? Peer into history and you’ll see a high degree of tension between the church and culture, or with political authorities. Consider Poland. The Catholic Church that gave us Pope John Paul II was the primary opponent of Soviet-controlled communism into the 1990s. As a result, the church plays a large role in national identity, especially since Poland faces an ongoing security threat from the nearby Russian colossus.

Now, let’s turn back to the American South. You’ll find again a high degree of tension between the church and culture, or political authorities. The South has the highest concentration of African Americans, and the church has been a pillar and unifying force in the black community in the face of marginalization and often outright persecution.

White Christians in the South might be in the majority and control much of their communities, even their states. But they see their identity in contrast with Northern progressives, especially those Yankees of New England. I don’t need to belabor the problems with this approach, going back to slavery and segregation. But even today, Southern identity sees its values threatened, and the church is the primary citadel for defense.

This tension can create problems, as history reveals. But some tension is also necessary for churches to be faithful to Scripture, as we see from the prophets to the apostles, and of course with Jesus himself. We see how it’s necessary when we study Christian movements that endure and spread. Larry Hurtado, scholar of second-century Christianity, offers a historical sociology of religion in his great book Destroyer of the Gods:

A successful religious movement must retain a certain level of continuity with its cultural setting, and yet it must also “maintain a medium level of tension” with that setting as well. That is, a movement must avoid being seen as completely alien or incomprehensible. But, on the other hand, it must also have what I mean by distinctives, distinguishing features that set it apart in its cultural setting, including the behavioral demands made upon its converts. There has to be a clear difference between being an insider to the group and an outsider.

In short, they’re accessible and odd. They’re not cults. But they’re not assimilated either. And that brings us to the second major clue.

2. Church and state are in tension.

I’ve visited and often done ministry in Geneva, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Boston, Edinburgh, London, Berlin, Amsterdam—some of the most secular cities in the world. At one point, they’ve all been among the most important Protestant cities in the world too. They have been or even remain today the capitals of established or official government Protestantism. And I don’t think that detail is incidental to our investigation.

I don’t say this just as a free church Baptist. I’m working inductively from the evidence. The established church can’t tolerate that tension with the state or culture Hurtado identifies with successful religious movements. The job of an established church is to facilitate social cohesion, to serve a political vision.

Depending on the country and time period, some established church leaders could still speak out against the government, to oppose a war, to condemn an immoral leader. You see that commonly now when it comes to economics or environmentalism. No Anglican bishops are quaking in their boots before they denounce a prime minister’s economic plan. Often, they are going with and not against the grain of the culture.

Far more rare is the bishop who speaks against assisted suicide, or abortion, or homosexuality. It may take a while, but eventually the established church catches up with where the culture and politicians have led. The tension must be relieved. Society must be stabilized and unified, with the church’s help.

Let’s go back to the Protestant element of this equation. The vision of the reformers, which I wholeheartedly support, combined an authentic inner spirituality with an applied public theology. The major reformers like Calvin and Luther worked in establishment contexts. They wanted to see spiritual revival through an authentic, unmediated encounter with God’s Word. And they wanted to see that Word applied in how society was ordered, in concert with government.

Walking around Copenhagen, I was reminded how successful their reforms have been. This is the world Protestantism created. Universal literacy. Widespread prosperity. Human-rights advocacy. Safe, clean streets aren’t just a top-down government program. They’re the bottom-up behavior of people who have internalized biblical commands over generations and generations. They come from a dynamic, innovative culture formed by Protestant learning aimed at serving the common good.

Protestantism normalized and universalized the interiority of Christianity. As we see so clearly in the Puritans of New England, Protestants expected everyone to experience an encounter with God, to obey from inward desire, not merely from outward conformity. Then, these Protestants expected their communities to become cities on a hill, beacons of righteousness when that faith was applied to all of life. It’s no surprise the Protestant countries of northern Europe have become famous for their generous social welfare programs. It’s their faith applied to society, at least when you’re prosperous enough to afford it.

Protestantism normalized and universalized the interiority of Christianity.

Protestantism normalized and universalized the interiority of Christianity.

So, then, what’s the problem? Why the secularism?

The church became a victim of its own success.

When everyone obeys from within, and the government takes care of every problem, what’s the purpose of the church? Who needs a sermon to tell you what you already know to do? You’ll be inside hearing about suffering from Romans 8, while outside the crowds are thinking, The government will take care of me when anything goes wrong. Christianity doesn’t feel necessary, as I heard in lament from many church leaders across the Nordics.

Expecting Too Much

There’s another problem that leads to secularism, and it’s particular to Protestantism. Charles Taylor faults the reformers for expecting too much of individuals and too much of society.

It’s easier to maintain a religion of rituals, of public performance. You go to Mass because you need to receive the host. And you don’t expect everyone to act like saints. That’s why we venerate the few as saints, not overburden the many. Taylor calls this problem Reform. The individual is justified by faith alone. It’s objective (apostle Paul). But the proof of faith is found in our works. It’s subjective (book of James). How do you know you’re justified if your works don’t contribute?

Taylor says Protestantism folds under the weight of its own heavy expectations. I’m not persuaded by this argument, but I recognize the force of it. Protestantism creates high expectations for individuals, which they must prove in their actions. Inevitably, in this fallen world, our actions will fall short. Society doesn’t always change. Sin isn’t eradicated. And we wonder if we’re truly saved, whether Christianity can actually work.

This public/private dynamic plays out in confusing ways among Europeans, ways I’ve struggled to understand in conversations with church leaders. You’ll find in secular Europe a peculiar linkage between a high degree of individual autonomy and a high degree of social conformity. Everyone, together, does their own thing. Church leaders tell me how hard discipleship is among people who can’t imagine being members of a church and submitting to leaders. But they willingly pay high taxes so that everyone will be on roughly the same economic level, with access to education and health care.

Once again, this is the enigma of secularism. Protestantism and its emphasis on individual Bible reading contributed to the rise of individualism in the West—the same individualism that now bucks against church teaching on sexuality, for example. And Protestantism also created this moral society that expects everyone to contribute toward the common good according to strongly held values.

So, what happened? How did established Protestantism go to seed and the church nearly disappear in the 20th and 21st centuries? The usual suspects include Nietzsche’s philosophy, Darwin’s natural selection, and Freud’s psychoanalysis. All played a major role. But now we need to add one final ingredient to this strange stew of secularism.

That ingredient is the crisis of the Second World War, the destruction of that city on a hill. Germany looks historic and venerable, but of course it’s been rebuilt on a new foundation after American and British bombs leveled most cities. Historically speaking, it’s a facade.

Historian Tom Holland in Dominion has shown how Christianity created much of what we know and value in Western civilization, including Europe. Alec Ryrie, in his new book The Age of Hitler, explains how Western leaders disguised that Christian influence to create a postwar consensus. Ryrie doesn’t fault Christians for starting the Second World War, as the established churches endorsed the First World War, to their enduring shame. Ryrie merely observes that Christian churches couldn’t prevent or stop the war.

And in the wake of two catastrophic wars in a matter of decades, Western leaders excluded Christianity from the postwar consensus. The United Nations produced a Universal Declaration of Human Rights without reference to God. Criticizing C. S. Lewis and his wartime lecture The Abolition of Man, Ryrie argues that in the age after Hitler, the world we inhabit still today, humanity has become our shared faith. In short, we need to be good (not like Hitler), and we don’t need God.

As Holland told me five years ago on Gospelbound, you can export and impose universal human rights on a war-torn world. But you can’t do the same with Christianity, discredited and discarded by war. Thus, to keep the peace, we share now a secular faith.

When Secularism Runs into Reality

I spent a memorable Friday afternoon with friends touring the National Gallery of Denmark, not far from the King’s Garden in central Copenhagen. The guide excitedly told us about a new exhibit on Surrealism, which she said has become popular again.

To keep the peace, we share now a secular faith.

To keep the peace, we share now a secular faith.

No wonder. Surrealism emerged in Europe as a response to the First World War. I can see why it’s popular again, as the postwar consensus of the Second World War has finally crumbled with Russia’s invasion of and ongoing war with Ukraine.

I don’t consider myself an expert in Surrealism, so I read the curator’s explanations of André Breton and his Second Surrealist Manifesto from 1929. Here’s one of those summaries:

Inspired by Freud’s psychoanalysis, the [Surrealists] see drives as a fundamental energy that moves human beings—not only towards life and creation but also towards dissolution and chaos. This is evident in their depictions of war, disintegrating bodies, and challenges to authority figures. . . . These artists allow themselves to be guided by their drives, which can lead to both the construction of new visions and the dismantling of existing norms.

You see and even feel in the Surrealists’ work the destruction suffered by a generation whose world was destroyed by war. You can also see that they didn’t intend to put the world back together the way they inherited it. There was no going back to July 1914. Guided by Freud, they’d be driven to reconstruct life however they pleased.

You can see why Surrealism is popular again. We’re not going back to the world before the COVID-19 global pandemic, or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or the terrorist attacks on Israel, or Germany before the bombs. Ryrie says we’re not going back to Christianity either. It’s not an option.

So we’ll need to make a new world, again, however we feel. We’ll be lucky if it lasts as long as the postwar consensus did. No one knows. We’re navigating the future without a compass, only our drives. This is modern Western secularism: We’ve internalized Christianity, but we won’t acknowledge it. We’ve publicized Christianity, but we won’t credit it. We’ve abandoned Christianity, but we don’t know how to replace it.

History is neither cyclical nor linear. We don’t know where we’re going, and we’re not just repeating the past. God often surprises us. The postwar consensus of secular universals once seemed impossible, then impregnable, and now unlivable.

It’s not unlivable because Copenhagen is a miserable place to live or visit. No, thanks to Christianity and Protestantism, it’s a marvelous place, a remarkable achievement. It’s unlivable because reality always wins. Once you’ve drunk your coffee and eaten your pastry, you have to walk home and do the laundry. The social welfare system might be great, but it’ll always fail you in the end. Romans 8 is true whether or not it feels like reality on a sunny September day.

Today, secularism is running into reality and losing. Reality remains inconvenient to those who deny God. The two genders are different. Not every metaphysic produces the same results, or even desirable results. Neighbors often desire to defeat or conquer their neighbors. We need a way to tolerate differences but maintain social cohesion. We need a shared basis for justice while preserving freedoms of conscience, speech, and assembly. We need help restraining the drives that destroy ourselves and others. There must be a purpose for progress beyond the cycles of fashion and our feeling of superiority over the past.

Today, secularism is running into reality and losing. Reality remains inconvenient to those who deny God.

Today, secularism is running into reality and losing. Reality remains inconvenient to those who deny God.

I see a future for the church in the most secular cities of the West. I heard about it from the leaders of TGC Norden. But their work often feels like pushing a boulder uphill while slipping on mud. They’re trying to prove the need for the solution they’re offering in the gospel. Most people are content to gaze into the blue skies with their coffee and pastries. They’re not wanting to think about death, to gaze into their souls, to question whether the numbing effects of their drives will ever get old or stale. Thank (not God? ourselves?) for the welfare state.

Three Threats to Secularism

Something is changing, however. These leaders told me what they think will happen. I’m summarizing three tensions that will soon demand widespread social action. And Surrealism won’t have answers. The West will need Christianity again.

1. Islam’s rise threatens secularism.

Religions thrive under moderate threats. The first threat to secularism and opportunity for Christianity is the rise of Islam, especially through immigration since 2015. Islam and secular humanism make strange bedfellows, despite their shared opposition to Christendom. Even Sweden isn’t happy after its failure to integrate large numbers of Muslim immigrants.

The problem with cloaking the Christianity that made your society possible is that you might actually forget what made your society plausible. Much of Europe is finding out that many Muslims don’t share their drives or their vision for the public good. The rise of Islam could make the secular West go looking for support and turn back to Christianity for survival.

2. Collapsing fertility threatens societies.

The second threat is related. The secular West isn’t the only place suffering a collapse in fertility. But the collapse started in the Nordics. It’s not just a problem that the social welfare system depends on younger workers and younger taxpayers. It’s that a society that won’t get married and have children is a society that has lost a sense of purpose, sacrifice, or even hope. Given the higher fertility rates in Islamic countries, Europe may face a simple math problem within one or two generations. Could Christianity restore hope and a vision for giving life to a new generation to steward the culture and values of these beautiful countries?

3. Security breaches threaten safety.

The third threat is even more pressing. Not many thought Sweden and Finland would join NATO—until they moved quickly to join after Russia invaded Ukraine. The end of the postwar consensus has centered basic security and survival questions once again. Drones swarmed and shut down the Copenhagen airport just hours after I left. An authoritarian axis between Russia, China, and North Korea could put much of the democratic, secular West in imminent danger.

Could Christianity remind these threatened countries why it’s worth defending themselves and their weaker brothers? Could their historic faith bring unity and resolve to meet this challenge, whatever the cost? Even Denmark’s secular prime minister thinks it could.

Christianity is truth and reality, whether or not we acknowledge Christ’s lordship. But in the secular West, our biggest hindrance is the lack of perceived or felt need by our neighbors—the lack of an imminent threat that wakes them up from secular slumber. We’re preaching Romans 8, and they’re enjoying the football match. Secularism is like an animal in a habitat with no known predators. Protestantism gave them peaceful and prosperous cities. What’s lost if the churches are empty? The buses still run on time. The food still shows up on the table. The welfare state still provides.

That need could become more widely felt under any or all of these three options. If so, how will we respond as Christians?

As Protestants, I hope, who believe the gospel brings transformation to individuals and societies. Like the reformers, we can’t settle for outward conformity. And I hope we’ll respond by not trying to resolve that tension between the church and culture and political authorities. Don’t fall for the establishment shortcut. It’s another dead end. Jesus told us to expect tribulation (John 16:33). And he promised he’ll carry us through any trials. He won’t fail us in the secular West either.

To watch or listen to this essay, check out the Gospelbound episode “3 Threats to Secularism in the West.”

The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics helps Christians share the truth, goodness, and beauty of the gospel as the only hope that fulfills our deepest longings. We want to train Christians—everyone from pastors to parents to professors—to boldly share the good news of Jesus Christ in a way that clearly communicates to this secular age.

Click the button below to sign up for updates and announcements from The Keller Center.

Join the mailing list »

Collin Hansen serves as vice president for content and editor in chief of The Gospel Coalition, as well as executive director of The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics. He hosts the Gospelbound podcast, writes the weekly Unseen Things newsletter, and has written and contributed to many books, including Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation and Rediscover Church: Why the Body of Christ Is Essential. He has published with the New York Times and the Washington Post and offered commentary for CNN, Fox News, NPR, BBC, ABC News, and PBS NewsHour. He edited the forthcoming The Gospel After Christendom and The New City Catechism Devotional, among other books. He is an adjunct professor at Beeson Divinity School, where he also co-chairs the advisory board.