Mission

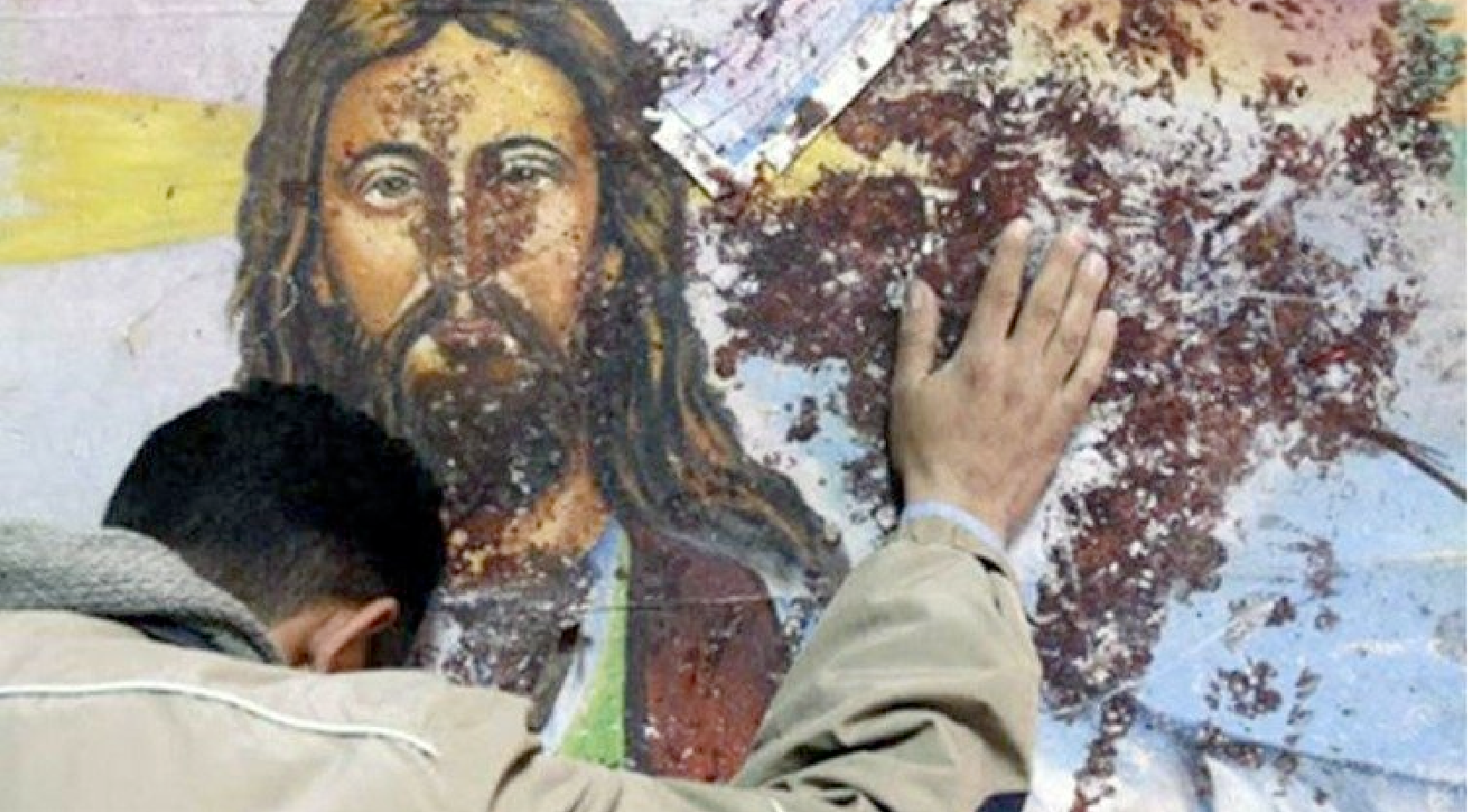

France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, and Austria lead the list of countries with the highest number of incidents. Photo: Vatican News

The Vienna-based observatory has documented 2,211 anti-Christian hate crimes committed in 2024, a figure assembled by triangulating police data, OSCE/ODIHR reports, and its own independent research to avoid duplications

(ZENIT News / Rome, 11.17.2025).- For years, Europe imagined itself as the exhausted battlefield of old religious conflicts, a continent that had learned from history and slowly matured into a model of coexistence. Yet a new body of research suggests that this self-image has become increasingly unmoored from reality. According to the latest findings from OIDAC Europe, attacks on Christians and Christian sites across the continent are rising at a pace that alarms even seasoned observers of religious freedom.

The Vienna-based observatory has documented 2,211 anti-Christian hate crimes committed in 2024, a figure assembled by triangulating police data, OSCE/ODIHR reports, and its own independent research to avoid duplications. The number is not merely higher; its composition has shifted. Personal attacks against Christians—assaults, threats, and in several cases deadly violence—jumped significantly. Arson targeting churches and Christian institutions nearly doubled, placing fire as one of the most common forms of hostility toward religious communities.

Behind the statistics is a geographic pattern that mirrors wider political tensions. France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, and Austria lead the list of countries with the highest number of incidents. In France, where authorities saw a modest decline in anti-Christian offenses between 2023 and 2024, the trend abruptly reversed. By mid-2025, reported attacks had risen by 13 percent. Violent Islamist plots, desecrated cemeteries, and high-profile cases such as the near-destruction of the historic church of Saint-Omer have forced the country to confront an unsettling question: how fragile is the religious heritage that anchors so much of its cultural identity?

Germany faces similar uncertainty, but for an entirely different reason. Official police statistics recorded a 22 percent rise in anti-Christian hate crimes, yet those numbers rely exclusively on acts designated as politically motivated. Much of the vandalism, arson, and harassment that Christians report does not fall under that classification and therefore disappears from the official record. In 2024, OIDAC documented thirty-three arson attacks on churches in Germany alone—far more than the government acknowledged. Bishops in the country have spoken publicly of an escalation so stark that, in their words, “every taboo has been broken.”

Spain, too, struggles with a reality that its institutions are ill-equipped to measure. The national government does not systematically track anti-Christian hate crimes, and yet independent observatories report double-digit increases in vandalism against churches, coupled with the tragic killing of a monk in an attack on a monastic community. When the structures responsible for documenting intolerance fail to keep pace with events, the result is an incomplete picture that hampers both prevention and response.

Perhaps the most revealing data, however, comes from places where Christianity remains woven into the fabric of public life. In Poland, a recent survey found that nearly half of Catholic priests experienced aggression in the past year. More than eighty percent never reported the incidents. If representative, the findings suggest that thousands of cases remain invisible to official statistics. A similar underreporting pattern has been identified in Spain and the United Kingdom, where Christians describe discrimination in workplaces and public institutions—experiences that seldom translate into formal complaints.

The trends are not limited to physical assaults. OIDAC’s new report dedicates substantial attention to legal pressures that Christian individuals and communities face in several European countries. Restrictions on silent prayer in designated “buffer zones,” prosecutions for quoting Scripture publicly, and attempts to regulate pastoral conversations under broad “conversion therapy” bans illustrate a patchwork of legislation that Christians perceive as increasingly punitive. Some of these cases have attracted international attention: a British veteran fined for praying silently outside an abortion clinic, a Finnish parliamentarian repeatedly tried for citing biblical passages, or German and French court rulings that removed Christian symbols from public institutions in the name of neutrality.

The freedom of parents to transmit their religious beliefs to their children has also become a flashpoint. A controversial ruling by Spain’s Constitutional Court granted a secular mother exclusive authority over her child’s upbringing, preventing the Protestant father from taking the child to church or reading the Bible with him. OIDAC argues that such decisions elevate secularism to a normative position while reducing religious education to something potentially harmful—a stance at odds with international human rights standards.

These developments unfold amid a broader European debate about the presence of religion in public life. Hospices run by Christian institutions in the United Kingdom face new pressures following the expansion of euthanasia legislation. Local courts in Germany have taken a restrictive view of cross displays in schools. Municipalities in France have ordered the removal of nativity scenes from public squares. Taken together, these cases form a mosaic of growing unease: Christianity remains culturally visible, but its visibility is increasingly contested.

The OSCE’s 2025 practical guide on responding to anti-Christian hate crimes—hailed by observers as a milestone—attempts to address some of these concerns by urging states to collect more reliable data, include Christian communities in security assessments, and strengthen training for law enforcement. But guidance alone cannot reverse years of fragmented reporting and political reluctance. The disparity between lived experience and official statistics continues to widen, fueling mistrust and leaving Christian communities feeling unprotected.

Europe’s Christian landscape has always been complex, shaped by centuries of faith and conflict, reform and secularization. What the new figures suggest is not a sudden crisis but the intensification of a long-running pattern: religious freedom cannot be preserved if the signs of hostility are ignored, minimized, or politicized. The continent that once exported its cathedrals, universities, and saints now must ask whether it can still safeguard the communities that built them.

Full report at this link.

Thank you for reading our content. If you would like to receive ZENIT’s daily e-mail news, you can subscribe for free through this link.

View all articles

Licenciado en filosofía por el Ateneo Pontificio Regina Apostolorum, de Roma, y “veterano” colaborador de medios impresos y digitales sobre argumentos religiosos y de comunicación. En la cuenta de Twitter: https://twitter.com/web_pastor, habla de Dios e internet y Church and media: evangelidigitalización.”

If you liked this article, support ZENIT now with a donation

To celebrate the World Day of the Poor and its Jubilee, the Congregation of the Mission organized the Holy Father’s lunch in the Vatican with people living in poverty.

Pope’s address to representatives of the film industry during a meeting at the Vatican