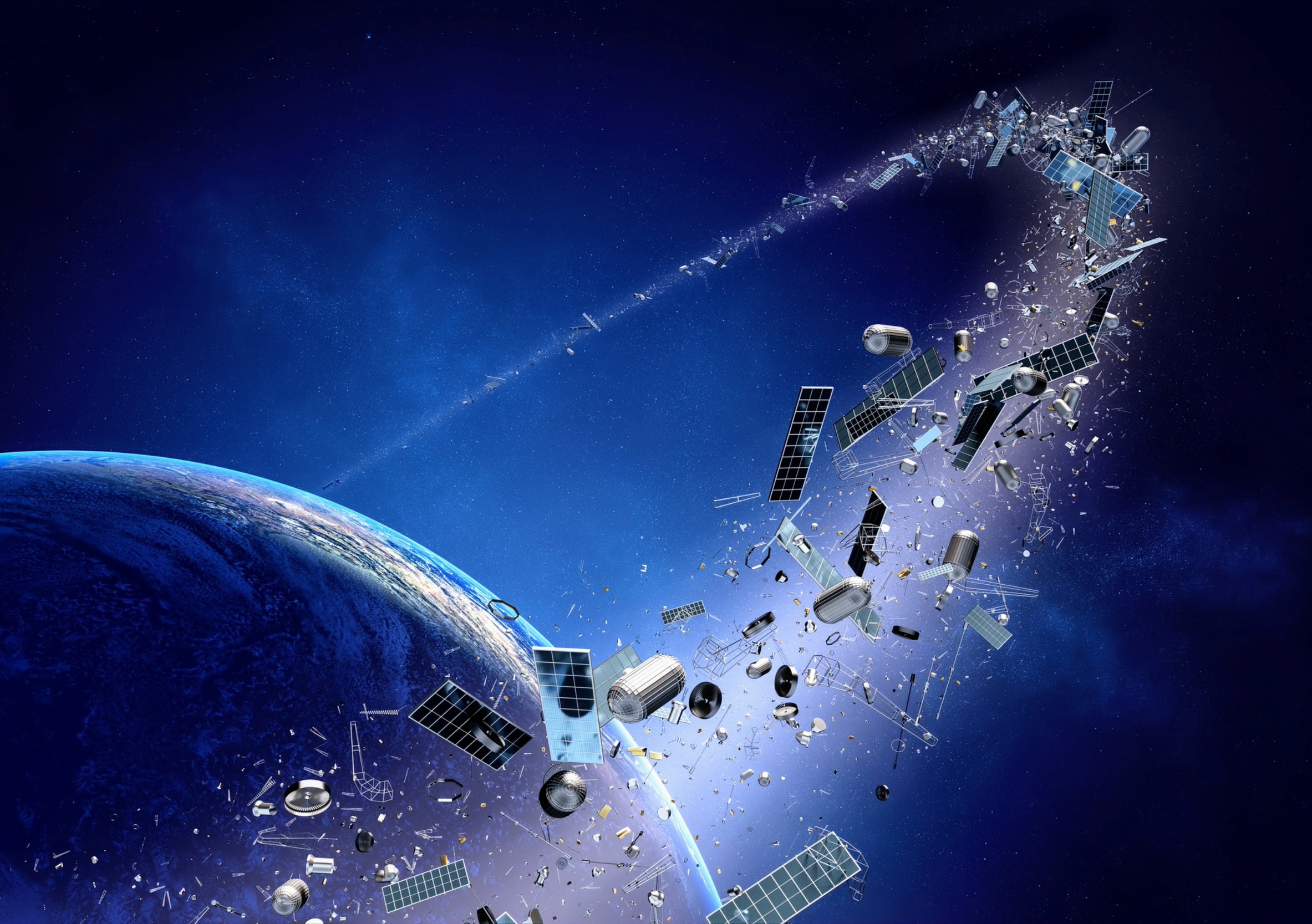

On October 19, the US Space Command revealed a troubling incident: the Intelsat 33e satellite broke into approximately 20 pieces, littering an already crowded space with large chunks of space debris.

The cause remains unknown, but the event has reignited serious concerns about the increasing accumulation of space junk in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

Experts warn that this growing problem could lead to the dreaded Kessler Syndrome, potentially rendering space exploration and satellite use impossible.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is a region of space that lies relatively close to Earth, typically between 100 and 1,200 miles (160 to 2,000 kilometers) above the planet’s surface.

It’s the most commonly used orbit for satellites and space stations because it’s cheaper and easier to reach than higher orbits.

In LEO, satellites orbit the Earth much faster, completing a full circle in just about 90 minutes. This means they can pass over the same spot on Earth several times a day, making LEO ideal for things like weather forecasting, communication, and Earth observation.

One of the most famous objects in LEO is the International Space Station (ISS), which orbits the Earth at about 250 miles (400 kilometers) above the surface.

LEO is also where most commercial communication satellites, as well as satellites for internet services, operate.

Their relatively low altitude means they can provide faster data transmission speeds and lower latency compared to satellites in higher orbits.

In 1978, NASA scientists Donald Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais introduced the concept of Kessler Syndrome – a dire prediction about space debris.

The experts theorized that as objects in orbit collide, the resulting debris could trigger more collisions. These repeated collisions would create a chain reaction, generating an increasing number of fragments in space.

This phenomenon could spiral out of control, leading to a heavily polluted orbital environment. If allowed to continue accumulating unchecked, the debris could render low Earth orbit completely unusable.

This would prevent future satellite launches, disrupt space exploration, and severely impact technologies that rely on satellites, such as GPS, internet, and weather forecasting.

Kessler Syndrome highlights the critical need to manage space debris effectively and prevent cascading collisions that could jeopardize humanity’s access to space.

“The Kessler Syndrome is going to come true. If the probability of a collision is so great that we can’t put a satellite in space, then we’re in trouble,” said John L. Crassidis, space debris expert at the University at Buffalo.

Space has become increasingly crowded. There are currently more than 10,000 active satellites orbiting Earth, with approximately 6,800 of these belonging to Elon Musk’s Starlink network.

Companies like SpaceX and Amazon aim to launch thousands more satellites, heightening the risk of collisions.

Since the dawn of spaceflight in 1957, there have been over 650 fragmentation events, including collisions, explosions, and deliberate satellite destruction.

In 2021, Russia destroyed one of its own satellites in a military test, creating over 1,500 traceable debris fragments.

“The size of the debris we are tracking ranges from small fragments roughly the size of a softball to larger pieces up to the size of a car door,” noted Bill Therien, CTO at ExoAnalytic Solutions.

“The majority of the tracked objects are on the smaller end of that spectrum, which contributes to the difficulty of consistently observing all the debris pieces.”

Congestion in orbit endangers astronauts and vital space-based technologies. For instance, the ISS has performed numerous evasive maneuvers to avoid debris.

In one recent incident, a piece of debris came within 2.5 miles of the ISS, forcing a Russian spacecraft to adjust its trajectory.

If satellites collide or go offline due to overcrowded space, critical services like GPS, broadband internet, and television could fail. Experts warn that this would cause widespread disruption to modern life.

Efforts are underway to address this growing crisis. The European Space Agency (ESA) is developing initiatives like Clearsat-1 in collaboration with Swiss startup ClearSpace to capture and deorbit defunct satellites.

Meanwhile, technologies such as drag sails aim to accelerate the natural descent of debris into Earth’s atmosphere.

However, tracking and mitigating debris remains a monumental challenge. The ESA estimates there are over 40,500 pieces of debris larger than 10 centimeters and millions of smaller fragments that current technology cannot reliably detect.

“Even with today’s best sensors, there are limits to what can be reliably ‘seen’ or tracked, and smaller space debris is often untrackable,” said Bob Hall, director at COMSPOC Corp.

Experts emphasize the urgency of international cooperation to establish binding space regulations.

The United Nations’ Pact for the Future aims to address space debris through frameworks for traffic and resource management. However, enforcement mechanisms are lacking.

“The biggest concern is the lack of regulation,” said Dr. Vishnu Reddy, a professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona. “Having some norms and guidelines that are put forward by the industry will help a lot.”

To sum it all up, as more satellites are launched into Low Earth Orbit (LEO), the risk of collisions and the potential for Kessler Syndrome — the runaway chain reaction of debris collisions — becomes an increasingly real threat.

With over 10,000 active satellites currently in orbit, the crowded space environment is putting everything from space missions to vital technologies like GPS and communication systems in jeopardy.

Experts warn that without significant efforts to manage and reduce space junk, we could face a future where space exploration and satellite services become nearly impossible.

Proactive measures – ranging from technological solutions to enforceable regulations – are crucial to safeguarding Earth’s orbit.

The key to avoiding the worst-case scenario of Kessler Syndrome lies in international cooperation and the establishment of strict regulations to prevent further overcrowding.

If action is not taken soon, the consequences could be catastrophic – not just for space exploration but for the many aspects of modern life that depend on satellite technology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–