Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Advertisement

Scientific Data volume 12, Article number: 177 (2025)

Metrics details

Following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the rise of long COVID, characterized by persistent respiratory and cognitive dysfunctions, has become a significant health concern. This leads to an increased role of complementary and alternative medicine in addressing this condition. However, our comprehension of the effectiveness and safety of herbal medicines for long COVID remains limited. Here, we present a single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset of peripheral whole blood cells derived from participants in a clinical study involving three commercially available herbal medicines, targeting fatigue and brain fog in long COVID. The dataset comprises 181,205 quality control (QC)-passed cells, along with clinical metadata, enabling a comparative analysis of immune cell populations before and after treatment. To ensure the technical validity of our dataset, we implemented rigorous quality checks throughout stages of the study, including sample preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic data analysis levels. This transcriptomic data may serve as a resource to deepen our insights into the role of herbal medicines in management of long COVID.

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, great efforts have been put by the scientific field into developing efficient treatment methods against the disease. Despite a substantial increase in vaccination rates, the prevalence of new COVID-19 cases remains significant1. Additionally, a new lingering concern is the emergence of long COVID, defined as a condition comprising persistent multisystemic symptoms after the clearance of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection2. Long COVID is characterized by a wide spectrum of symptoms that manifest across several organs, including dyspnea, lung inflammation, brain fog, and cognitive impairment due to prolonged damage of the central nervous system3. As the symptoms of long COVID are diverse, establishing effective treatment strategies is challenging. Several sources provide evidence suggesting efficacy of complementary herbal medications in managing both COVID-19 and long COVID3,4,5,6,7. Such interventions have shown favorable effects on sputum production, faster remission from fever and coughing, and shorter duration of hospital stay. However, the underlying mechanism of action of such herbal medications remains unclear.

Analyzing immune cells in human blood has provided great insights into the coordinated response to viral infections such as SARS-CoV-28,9. Several techniques, such as flow cytometry, mass cytometry, immunohistochemistry, microarray analyzes, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) are commonly used to study immune cell populations in COVID-198,10,11,12,13,14. Among these techniques, scRNA-seq offers several advantages, enabling high resolution profiling of transcriptomes from thousands of individual cells, identification of rare cell types, and characterization of cell dynamics15,16. Thus, a single-cell-level dataset inquiring the heterogeneity of immune cell populations would help understand the contribution of medicinal plants in patients’ clinical outcomes and support evidence for their use in long COVID. Up until now, numerous scRNA-seq datasets studying immune responses in COVID-19 and long COVID have been published8,14,17,18. However, a dataset exploring the activity of herbal medicines on immune-related gene expressions in long COVID patients is still absent.

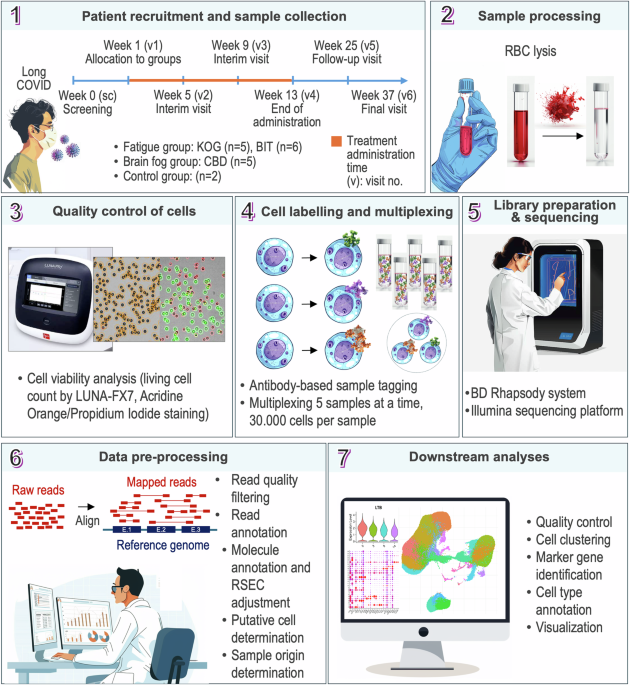

Here, we introduce a dataset of peripheral blood samples, containing a total of 181,205 cells, collected from 18 participants involved in clinical trials using herbal medicine to manage long COVID symptoms (Fig. 1). Blood samples from the 2 healthy volunteers and 16 participants in a clinical trial including 11 with fatigue symptoms and 5 with brain fog symptoms were included in this data set. Over 37 weeks, the patients followed a schedule of clinical evaluation, involving symptom evaluations, drug administration, and blood collection. We processed the samples to remove red blood cells, labeled them according to BD Rhapsody system, and utilized them for a multiplexed sequencing analysis. We performed scRNA-seq with an Illumina platform and pre-processed the obtained reads following the BD Rhapsody WTA analysis pipeline. For validation, we generated extensive quality control reports on sequencing, library, and reads quality. Finally, we employed the R Seurat package to characterize present cell populations and visually assess the data quality. Our transcriptomic dataset may serve as a valuable foundation for future studies on the effects of herbal medicines on long COVID.

Workflow of the study. Data from 16 participants who were allocated into herbal medicine treatment groups were obtained during the participation of a clinical trial. Intervention used in this clinical trial included treatments with commercially available herbal medications for 12 weeks. Blood samples were taken for scRNA-seq, and CIS score was measured to monitor the outcome of the treatment. Peripheral whole blood cells were extracted from the collected blood specimens by RBC lysis. After cell viability assessment, the samples were labelled and grouped for a multiplexed sequencing analysis. Library preparation and data pre-processing was conducted according to BD Rhapsody protocol. For downstream bioinformatic analysis, R Seurat package was utilized to perform additional QC, cluster, and annotate the cells.

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of commercially available herbal medicines in treating long COVID, 45 participants with long COVID symptoms were recruited to the Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital, as approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital (IRB approval no. KOMCIRB 2020-12-002-001). Participants’ inclusion criteria included age between 19 and 65 years old, symptoms of fatigue or cognitive dysfunction persisting for more than four weeks post-COVID-19, and a total score of more than 76 points on the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included allergies to herbal medicines, pregnancy, or other medical conditions causing fatigue or cognitive issues, which may impact the study. Research Subject Consent forms were acquired from all human participants who agreed with the collection, provision and entrustment of personal information to third parties. The participants consented to the publication of the data. After the first visit, the patients were allocated to treatment groups based on their symptoms and were prescribed one of three Korean Medicine herbal medications for a time span of 12 weeks (Table 1). Among these 45 participants, blood samples of the 18 participants were completely collected and passed through the quality control (QC) process. Participants with fatigue symptoms received Kyungok-go (KOG, n = 5) or Bojungikgi-tang (BIT, n = 6), while brain fog patients received Cheonwangbosim-dan (CBD, n = 5). Additionally, 2 healthy individuals were recruited as control. The treatment outcome was assessed using a CIS score, in a form of a patient self-evaluation questionnaire, instructed by the principal investigator during visits 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (Fig. 2). The patient’s peripheral blood was collected, 25 mL at visits 0, 4, 5, and 6. Details on the clinical study workflow and other measures are described in our published protocols and online at Clinical Research information Service (CRIS)19,20 (https://cris.nih.go.kr/cris/search/detailSearch.do?seq=20001&search_page=L).

CIS scores of the patients from KOG (left), BIT (middle), and CBD (right) treatment groups at respective timepoints (CIS < 76 considered normal, CIS ≥ 76 considered considerable fatigue).

Blood samples from the study participants (n = 16) included in this study were obtained at visits 0, before treatment, and 4, after the treatment period was completed and blood samples from the normal control were obtained once. Isolation and quality control (QC) of single cells from these specimens were applied on the same day as their collection. Peripheral whole blood cells, including lymphocytes, myeloid, and dendritic cells are a critical component of both innate and adaptive immune response against viral infections21,22. To extract these cell populations, whole blood samples were collected on EDTA tubes and removal of red blood cells (RBC) was conducted via lysis. First, 1xRBC lysis buffer was added to the blood specimens in a 1:3 ratio and mixed by inverting the tube for 10 minutes in room temperature. The samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes, at 300 g RT and formed supernatant was removed. Next, the samples were resuspended in 0.04% BSA/PBS and the centrifugation and supernatant removal steps were repeated. If the RBCs were removed successfully (no red color visible in the cell pellet), the cell pellets were again resuspended in 0.04% BSA/PBS to obtain 2 × 106 ~1 × 107 cell count level aliquot cell stock. Lastly, cell viability after RBC lysis was assessed via acridine orange (AO)/propidium iodide (PI) fluorescent staining and the percentage of living cells in a cell suspension was calculated using LUNA-FX7 (logos biosystems) automated cell counter (Figure S1).

Library preparation was performed according to BD Rhapsody System mRNA whole transcriptome analysis (WTA) and sample tag protocol (https://scomix.bd.com/hc/article_attachments/13726971116813)23, as this technology enables to monitor cell viability and shows lesser tendency to form cell doublets, comparing to other platforms24. Previously prepared cell suspensions were labelled with antibody-based sample tags, washed twice, and counted. If unaggregated antibodies were still present in the samples after the washing step, additional filtering was applied using Sigma Flowmi cell strainers. Clean samples were utilized for a multiplexed single-cell capture (5 samples at a time, 30,000 cells per sample). In brief, single cells were captured in individual wells using magnetic beads, and lysed to release cellular contents, including mRNA. For WTA library generation, the released mRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA on the Cell Capture Beads. The corresponding cDNA was amplified using random priming and extension approach, followed by an index PCR step introducing unique molecular identifiers (UMI) to the samples. At the same time, the barcode information from Capture Beads was also added to Sample Tags during reverse transcription. To generate the Sample Tag sequencing libraries, the extended Sample Tags were first denatured from the Capture Beads, followed by a series of PCR steps to amplify them. Processed WTA and sample tag libraries were combined for each sample and utilized for sequencing with Illumina HiSeq X Ten sequencing platform, at 151 cycles for both reads (R1 and R2).

The initial Illumina basecall files (*.bcl) were converted to FASTQ format using bcl2fastq2 (v2.20.0) and the obtained read pairs were processed to generate single-cell expression profiles according to BD Rhapsody WTA Analysis Pipeline (v1.11) (https://www.bdbiosciences.com/content/dam/bdb/marketing-documents/resources-pdf-folder/Guide-User-SCM-Bioinformatics-ruo.pdf). Low-quality reads were filtered out from the input FASTQ files based on length (R1 < 60 bp, R2 < 40 bp), single nucleotide frequency (≥55% for R1 or ≥80% for R2), and mean base quality (<20 for both R1 or R2). Annotation of R1 reads was performed by identification of cell labels and UMIs, while R2 reads were aligned to reference human genome (GRCh38) using STAR (v2.5.2)25. Annotated reads with the same UMIs were combined and collapsed into raw molecules. Any present artefacts were removed based on recursive substitution error correction (RSEC) of UMI. To minimize the noise caused by excessive cell labels, putative cells were identified via second derivative analysis. Additionally, since the different samples were sequenced in a multiplexed manner, the information on sample of origin was retrieved using the BD Rhapsody sample determination algorithm prior to generation of the final gene expression matrices. The algorithm matches cells to their respective samples of origin using the sample tags introduced previously during library preparation. It identifies high-quality singlets as putative cells with more than 75% of sample tag reads derived from a single tag. To minimize the impact of cells with very low signal reads on the data, a minimum sample tag read count threshold is set. Only the putative cells which meet the threshold are considered successfully labelled with their respective sample tag, while the remaining sample tag reads are treated as noise. Since sample tag counts can vary among cells, the noise levels may also be different. The algorithm adjusts for the noise by calculating the expected noise level for each cell based on total sample tag count. Cells with high counts (>75%) from at least two sample tags and exceeding the expected noise thresholds are labeled as multiplets, while cells with very low sample tag counts that did not meet any threshold are noted as undetermined. Only the high-quality singlets are included in the generation of the gene expression matrices. After demultiplexing, output BAM files were annotated with genomic features, using the GRCh38 genome annotation file. Apart from BAM files, RSEC-corrected molecules and reads per gene per cell matrices were generated. Additionally, quality control files were obtained, including sequencing, library, alignment, reads, molecules, sample tag, and cell-level metrics.

Using Python (v3.10.12) anndata package (v0.10.5)26,27 the gene expression matrices of each sample were converted from csv to AnnData objects and merged. In RStudio (v4.1.1)28, the AnnData object was converted into a Seurat object via Convert and LoadH5Seurat functions. Next, using R Seurat package (v4.1.0)29 a standard workflow for data pre-processing and cell clustering was followed, including quality control, normalization, feature selection, data scaling, dimensional reduction by principal component analysis (PCA), clustering, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) reduction, and visualization. Quality control of consisted of filtering the gene-cell matrix such that cell with counts from mitochondrial genes below 25 percent and number of features more than 900 were included. After normalization, top 2000 variable genes were selected (via variance-stabilizing transformation) for further analysis and the number of included principal components (PCs) was determined based on JackStraw plots and Elbow plots (n = 20). Cell clustering was conducted using FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions, and non-linear dimensional reduction was managed by RunUMAP function. We classified the identified clusters using positive (avglog2FC > 0) cell type-specific markers found via FindAllMarkers function. For visualization of the clinical metadata, we generated UMAP plots grouped by treatment group, time, and CIS score, as well as bar plots showing differences in cell type proportions between the groups.

We present a single-cell transcriptomic dataset of immune cell populations from long COVID patients treated with herbal medicines. The clinical part of the study was registered in the national clinical trial registry Clinical Research Information Service, which is a primary registry of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (KCT0006252). Our final dataset consists of 181,205 high-quality single cells from 18 participants, including patients suffering from fatigue or brain fog symptoms, as well as healthy controls. Figure 1 provides an overview of the clinical, laboratory, and bioinformatical workflow, while information about the study groups is shown in Tables 1, 2. Raw sequencing data (fastq files) and matrix of processed counts from the final scRNA-seq dataset can be found in NCBI GEO under the accession number GSE265753 (https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE265753)30. Sample-level RSEC count matrices and collected cell-level metadata (two levels of cell type classification, sample, patient id, treatment, time, CIS score, sequencing set and analysis information) are available at Github, in the Releases as “RSEC_MolsPerCell” file, and in the “data” folder as “metadata” file, respectively (https://github.com/kprazano/longCOVID.git), as well as at figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7129264)31, under the same names. Additionally, QC and technical metrics files are available in the Supplementary Information file (Tables S1–3). Since the multiplexing set-level metrics (Table S2) were collected by grouping 5 samples at a time, Set5 contains one sample which was not included in the analysis. Sample-level metrics (Table S3) include only the 34 samples included in the study.

Effective isolation of single cells from tissue samples is a critical step of successful scRNA-seq. Using fresh specimens reduces cellular stress and RNA degradation, resulting in preservation of cell viability and overall higher sample quality32. Importantly, sample processing in our study was conducted immediately after collection and the samples were not frozen at any timepoint, which is an advantage of our workflow. We assessed viability of the extracted peripheral whole blood cells prior to sequencing by AO/PI staining and calculating the concentration of living cells (Figure S1). For all included samples, the average cell viability was 81.7% (68.5% – 94.2%) and live cell concentration was 5 × 105/ml or higher, indicating optimal quality (Table S1). Therefore, loading 30,000 cells per sample to the multiplexing sets should be adequate to capture a sufficient number of high-quality cells in the scRNA-seq.

As the sequencing analysis was completed, we evaluated quality of the obtained reads based on the reports from BD Rhapsody pre-processing pipeline. The initial number of input reads ranged from 1.11 billion to 1.25 billion across different sequencing sets. Quality filtering resulted in an average of 6.88% (5.51% – 7.87%) reads being filtered out, suggesting satisfactory quality of majority of the reads. For each set, over 56% of the QC-passed reads aligned uniquely to the transcriptome. At the level of individual samples, the average number of read pairs per molecule was over 1.8, and an average of 7,000 putative cells were identified (239,382 cells in total), indicating sufficient sequencing depth and cell capture ability. To further evaluate the efficiency of the putative cell calling step, we generated cell calling graphs showing the results of the second derivative analysis (Fig. 3). In each plot, only one distinct inflection point is present, indicating that the cells are well represented by molecules from library preparation. Moreover, the drop representing the inflection is visually sharp and can be clearly identified for each sequencing set, suggesting successful separation of putative cells from the noise. For sample-level cell quality control, we generated knee-plot graphs showing RSEC-corrected counts per barcode for the putative cells. High-quality cells are commonly considered to have >500 UMIs per cell33,34. The minimal RSEC-corrected UMI count for each sample varies between 463 and 2882 (990 on average), which indicates efficient removal of poor-quality cells with low UMI count (Figure S2). Altogether, the above QC measures highlight the robustness of the sequencing analysis and the technical validity of our data. Further details on sequencing set- and sample-level quality metrics are presented in the Supplementary Information file (Table S2, S3).

Cell calling graphs of RSEC-corrected reads per cell showing the results of the second derivative analysis for putative cell identification in each sequencing set. The arrow indicates the inflection point.

Our final dataset comprised samples from each patient before (sc) and after (v4) treatment, along with two control samples, 34 samples in total (Table 2). The dataset was processed following the standard workflow for scRNA-seq data analysis with R Seurat package29 (https://satijalab.org/seurat/articles/pbmc3k_tutorial) (Figure S3). The sample tag-based library preparation has been previously shown to lead to possible impairment of RNA quality and, subsequently, lower gene detection rate35. To evaluate the quality of our final dataset, we implemented several QC metrics, such as percentage of counts from mitochondrial genes, number of total counts, and number of features. (Fig. 4a,b, Table 2). The average mitochondrial gene percentage combined for all samples in our dataset is 12.57%. Given the variability in filtering criteria for this metric across scRNA-seq studies8,14,36, we searched for studies with workflows most similar to ours, specifically those utilizing BD Rhapsody for sequencing blood samples in COVID-1937. Based on this information, we filtered out cells with ≥25% of mitochondrial read count, potentially representing dying cells. RNA capture performance can be assessed by investigating the total number of counts detected per cell35. The number of captured transcripts in our samples ranges from 1468 to 68862 (7724 on average), suggesting a sufficient number of RNA molecules was captured. Additionally, we excluded cells with a count of unique features less than 900, indicative of potentially damaged or low-quality cells. After QC, the final dataset comprised 181,205 high quality cells.

Quality of the scRNA-seq dataset. (a) Violin plots showing the percentage of counts from mitochondrial genes and number of unique genes per cell, split by sample. (b) Violin plots showing the percentage of counts from mitochondrial genes and number of unique genes per cell, split by sequencing set. (c) Heatmap clustering of correlation coefficients across the sequencing sets. (d) PCA plot of the final dataset, colored by sequencing sets. (e) Distribution of cells from each sequencing set together in the final UMAP embedding. (f) Distribution of cells from each sequencing set separately in the final UMAP embedding.

Multiplexed scRNA-seq with BD Rhapsody allows for investigation of multiple samples at a time, while minimizing the risk of batch effect and reducing the cost of scRNA-seq assay as comparatively to other methods, such as 10X35. Given that our dataset originates from a multiplexed analysis, our next objective was to assess the heterogeneity of the data and the efficiency of cell clustering across different multiplexing sets (Fig. 4c–f). High Pearson correlation values suggest consistent gene expression patterns across the different sets, indicating good reproducibility of measurements among multiplexing sets, with minimal technical variation (Fig. 4c). Plotting cells based on PCA reduction also revealed no alarming issues, suggesting presence of three main cell populations, and a low number of potential outliers (Fig. 4d). In the final UMAP projection, cells from each set exhibit a satisfactory distribution among obtained clusters, indicating an efficient clustering process, where cells are grouped based on their biological state, without apparent batch effect (Fig. 4e,f). In summary, despite potential limitations, the presented state of our final dataset reflects the efficiency of the sample tag-based multiplexed sequencing. Additional quality control ensured selection of cells with the best quality, while maintaining a sufficient number of single cells for downstream analyses.

Presence of diverse cell types in a scRNA-seq dataset reflects satisfactory complexity of the transcriptome libraries and highlights its usefulness for downstream analyses. Since long COVID is associated with immune dysregulation17, the data was generated from peripheral blood samples, which should include a variety of immune cell populations. To create comprehensive cell type annotations, we applied two resolutions (0.1 and 1.0) during cell clustering. Using the lower resolution we identified 12 main cell types (Fig. 5a,b, Figure S4a), further divided into 27 subtypes in high-resolution level 2 annotation (Fig. 5c,d, Table 3). The main cell types include T (CD3D+), NK (NCAM1+), proliferating (MKI67+), plasma (IGHG1+), B (MS4A1+), classical monocytes (CD14+), non-classical monocytes (FCGR3A+), platelets (PF4+), dendritic (DC) (CD1C+), hematopoietic stem and progenitor (HSPC) (CD34+), mixed, and one cluster of unassigned cells. The mixed cells show expression of markers associated with both B cells (MS4A7, BANK1, CD79B) and myeloid cells (FCN1, S100A8, CD14), while the initially unassigned cells expressed genes suggesting a non-specific immune phenotype (ATG7, SLC8A1, FOXO1), possibly associated with autophagy38,39. To exclude the probability of sample contamination, we investigated the expression of RBC, fibroblast, endothelial, and epithelial cell markers, and confirmed that expression of these genes was insignificant in our dataset (Figure S4d,e). The unassigned cells, although not clearly characterized, meet our quality control threshold, and might represent differentiating or rare cell type. After careful consideration, we decided to retain these cells in our final dataset.

Cell types of the scRNA-seq data set. (a) UMAP plot showing level 1 of cell type annotation. (b) Dot plot of gene markers used for level 1 annotation. (c) UMAP plot showing level 2 of cell type annotation. (d) Dot plot of gene markers used for level 2 annotation.

Several sources report persistent activation of T cells in long COVID, leading to their dysregulation and prolonged inflammation40,41. Subtyping of T cells, the most abundant cell population in our dataset (80,876 cells), revealed 9 clusters, including a variety of naïve, activated, memory, effector, and exhausted T cells. Additionally, expression of T and NK cell markers was identified in the proliferating cell cluster, suggesting presence of cycling T and NK cells. Second most abundant cell type, classical monocytes (43,938 cells), were divided into subtypes based on top highly expressed markers specific for each Seurat cluster. This way, TPPP3+, CYP1B1+, IFI+, and early (CD14, FCN1, CD163low) classical monocytes were characterized. Moreover, we found a subset of neutrophils in our dataset (CXCL8 + AQP9 + G0S2+). Neutrophils, although often underrepresented in scRNA-seq datasets due to their short lifespan, are now gaining attention in long COVID studies42,43. Therefore, presence of neutrophils in our dataset makes it useful for future analyses. DCs are another cell type playing a key role in response against SARS-CoV-2, facilitating activation of other immune cells and producing antiviral cytokines44. However, the long-term effects of DC antiviral activity, especially in plasmacytoid DCs (pDC), are not well understood45. In our dataset, we identified subsets of pDCs and monocyte derived DCs (moDC) within the main DC cluster (3,912 cells). Lastly, we found 3 subtypes of B cells (15,699 cells), including immature, mature naïve, and memory B cells. The impact of these B cell states on COVID-19 convalescence is also an active area of research46,47. Importantly, clear expression of cell type-specific marker genes in the clusters (Fig. 5b,d) implicates a robust gene coverage and capture of transcriptional heterogeneity in our data. Therefore, our cell type classification may be a valuable foundation for future studies and deepen our understanding on changes in the immune cell population in long COVID. Additionally, we curated cell-level metadata incorporating crucial clinical information such as treatment type, time, and CIS score, to facilitate exploration of cell heterogeneity among different study groups (Figure S4f–h). Taken together, we provide a comprehensive and reliable scRNA-seq dataset for human long COVID.

We would like to remind the users who wish to analyze the data starting from raw sequencing data (fastq files available at GEO under accession number GSE265753)30 that results shown in this paper were generated after pre-processing the raw reads using BD Rhapsody WTA Analysis Pipeline (v1.11). The sample multiplex option can be selected when starting the analysis pipeline. Apart from adding the multiplexing option, no custom code or thresholds different from the default were used. For users interested in accessing sample-level data, we provide RSEC-corrected molecule count matrices, which can be found in Github (https://github.com/kprazano/longCOVID.git) and figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7129264)31. However, it is important to note that these matrices represent adjusted counts rather than raw data. Finally, users can also work with fully processed counts from the final scRNA-seq dataset, where all samples have been combined into a single matrix. This merged matrix (available as “GSE265753_processed_counts_matrix” file at GEO GSE265753)30 can be directly loaded and analyzed with R Seurat package.

While reusing this dataset, researchers should be mindful of the fact that the included controls are derived from healthy individuals and not untreated long COVID patients. The users may utilize our dataset alone or integrate it with other long COVID or COVID-19 studies, with consideration of batch effect. Nevertheless, we believe analyzing time-dependent samples from our dataset would be useful in evaluation of effectiveness of herbal medication in long COVID and identification of common factors among the three treatment groups.

Python script used for data format conversion (csv to Anndata) can be found in Github (https://github.com/kprazano/longCOVID.git), in the “codes” folder, as “data_formatting.py” file. Our R codes used for Seurat object-level quality control of the data, cell clustering and annotation, as well as generation of the figures presented in this paper (apart from cell calling plots from Figure S2, which were automatically generated during the BD Rhapsody WTA pipeline) are available in the same directory as “downstream_analysis_codes.R” file.

WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (2024).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Author Correction: Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 21, 408, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00896-0 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kim, T. H., Jeon, S. R., Kang, J. W. & Kwon, S. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Long COVID: Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 7303393, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7303393 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Ang, L. et al. Herbal Medicine Intervention for the Treatment of COVID-19: A Living Systematic Review and Cumulative Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 13, 906764, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.906764 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Demeke, C. A., Woldeyohanins, A. E. & Kifle, Z. D. Herbal medicine use for the management of COVID-19: A review article. Metabol Open 12, 100141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metop.2021.100141 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Li, L. et al. Effects of Chinese Medicine on Symptoms, Syndrome Evolution, and Lung Inflammation Absorption in COVID-19 Convalescent Patients during 84-Day Follow-up after Hospital Discharge: A Prospective Cohort and Nested Case-Control Study. Chin J Integr Med 27, 245–251, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11655-021-3328-3 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhi, N. et al. Treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in one convalescent patient with corona virus disease 2019 by oral traditional Chinese medicine decoction: A case report. J Integr Med 19, 185–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2020.11.005 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stephenson, E. et al. Single-cell multi-omics analysis of the immune response in COVID-19. Nat Med 27, 904–916, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01329-2 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Woodruff, M. C. et al. Extrafollicular B cell responses correlate with neutralizing antibodies and morbidity in COVID-19. Nat Immunol 21, 1506–1516, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-020-00814-z (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Kumari, D. et al. Flow cytometry profiling of cellular immune response in COVID-19 infected, recovered and vaccinated individuals. Immunobiology 228, 152392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2023.152392 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Burnett, C. E. et al. Mass cytometry reveals a conserved immune trajectory of recovery in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Immunity 55, 1284–1298 e1283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2022.06.004 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Rakheja, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Immunohistochemistry In Placenta. Int J Surg Pathol 30, 393–396, https://doi.org/10.1177/10668969211067754 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Celikgil, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 multi-antigen protein microarray for detailed characterization of antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. PLoS One 18, e0276829, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276829 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ren, X. et al. COVID-19 immune features revealed by a large-scale single-cell transcriptome atlas. Cell 184, 1895–1913 e1819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.053 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Tang, F. et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods 6, 377–382, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1315 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Jovic, D. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: A brief overview. Clin Transl Med 12, e694, https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.694 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Yin, K. et al. Long COVID manifests with T cell dysregulation, inflammation and an uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol 25, 218–225, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01724-6 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Vaivode, K. et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Alterations in Patient Immune Cells with Pulmonary Long COVID-19 Complications. Curr Issues Mol Biol 46, 461–468, https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46010029 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jegal, K. H. et al. Herbal Medicines for Post-Acute Sequelae (Fatigue or Cognitive Dysfunction) of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Phase 2 Pilot Clinical Study Protocol. Healthcare (Basel) 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101839 (2022).

Kim, T. H. et al. Herbal medicines for long COVID: A phase 2 pilot clinical study. Heliyon 10, e37920, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37920 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bispo, E. C. I. et al. Differential peripheral blood mononuclear cell reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 proteins in naive and previously infected subjects following COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Immunol Commun 2, 172–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clicom.2022.11.004 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Luukkainen, A. et al. A Co-culture Model of PBMC and Stem Cell Derived Human Nasal Epithelium Reveals Rapid Activation of NK and Innate T Cells Upon Influenza A Virus Infection of the Nasal Epithelium. Front Immunol 9, 2514, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02514 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Shum, E. Y., Walczak, E. M., Chang, C. & Christina Fan, H. Quantitation of mRNA Transcripts and Proteins Using the BD Rhapsody Single-Cell Analysis System. Adv Exp Med Biol 1129, 63–79, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6037-4_5 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gao, C., Zhang, M. & Chen, L. The Comparison of Two Single-cell Sequencing Platforms: BD Rhapsody and 10x Genomics Chromium. Curr Genomics 21, 602–609, https://doi.org/10.2174/1389202921999200625220812 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Virshup, I., Rybakov, S., Theis, F. J., Angerer, P. & Wolf, F. A. anndata: Annotated data. bioRxiv, 2021.2012.2016.473007 https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473007 (2021).

Wolf, F. A., Angerer, P. & Theis, F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol 19, 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-017-1382-0 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

RStudio: Integrated Development for R. (RStudio, PBC., 2020).

Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol 33, 495–502, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3192 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Prazanowska, K.H, Lim, S.B. GEO. https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE265753 (2024).

Prazanowska, K. & Lim, S. B. A. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Dataset of Peripheral Blood Cells in Long COVID Patients on Herbal Therapy. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7129264 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Jacobsen, S. B., Tfelt-Hansen, J., Smerup, M. H., Andersen, J. D. & Morling, N. Comparison of whole transcriptome sequencing of fresh, frozen, and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cardiac tissue. PLoS One 18, e0283159, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283159 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gao, S. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing coupled to TCR profiling of large granular lymphocyte leukemia T cells. Nat Commun 13, 1982, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29175-x (2022).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Ocasio, J. K. et al. scRNA-seq in medulloblastoma shows cellular heterogeneity and lineage expansion support resistance to SHH inhibitor therapy. Nat Commun 10, 5829, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13657-6 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Salcher, S. et al. Comparative analysis of 10X Chromium vs. BD Rhapsody whole transcriptome single-cell sequencing technologies in complex human tissues. Heliyon 10, e28358, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28358 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Triana, S. et al. Single-cell analyses reveal SARS-CoV-2 interference with intrinsic immune response in the human gut. Mol Syst Biol 17, e10232, https://doi.org/10.15252/msb.202110232 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

De Domenico, E. et al. Optimized workflow for single-cell transcriptomics on infectious diseases including COVID-19. STAR Protoc 1, 100233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2020.100233 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Collier, J. J., Suomi, F., Olahova, M., McWilliams, T. G. & Taylor, R. W. Emerging roles of ATG7 in human health and disease. EMBO Mol Med 13, e14824, https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202114824 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cheng, Z. The FoxO-Autophagy Axis in Health and Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 30, 658–671, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.009 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Yin, K. et al. Long COVID manifests with T cell dysregulation, inflammation, and an uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.09.527892 (2023).

Santopaolo, M. et al. Prolonged T-cell activation and long COVID symptoms independently associate with severe COVID-19 at 3 months. Elife 12 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.85009 (2023).

Shafqat, A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and long COVID. Front Immunol 14, 1254310, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1254310 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Woodruff, M. C. et al. Chronic inflammation, neutrophil activity, and autoreactivity splits long COVID. Nat Commun 14, 4201, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40012-7 (2023).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Alamri, A., Fisk, D., Upreti, D. & Kung, S. K. P. A Missing Link: Engagements of Dendritic Cells in the Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Int J Mol Sci 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031118 (2021).

Van der Sluis, R. M., Holm, C. K. & Jakobsen, M. R. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells during COVID-19: Ally or adversary? Cell Rep 40, 111148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111148 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shuwa, H. A. et al. Alterations in T and B cell function persist in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Med 2, 720–735 e724, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.013 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Lapuente, D., Winkler, T. H. & Tenbusch, M. B-cell and antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2: infection, vaccination, and hybrid immunity. Cell Mol Immunol 21, 144–158, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-023-01095-w (2024).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Download references

The clinical part of this study was conducted at Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University KM Hospital (IRB approval no. KOMCIRB 2020-12-002-001). This study was supported by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KSN2121220). Processing of the human-derived specimens, sequencing analysis, and initial data pre-processing was conducted in cooperation with ROKIT GENOMICS Inc. (Seoul, Korea). Downstream analysis of the scRNA-seq data was executed at the Ajou Precision Medicine Laboratory at the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Ajou University School of Medicine. K.H.P. and S.B.L. acknowledge support provided by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (2020R1A6A1A03043539, 2020M3A9D8037604, and 2022R1C1C1004756), as well as funding from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HR22C1734).

Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, 16499, South Korea

Karolina Hanna Prazanowska & Su Bin Lim

Department of Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Ajou University, Suwon, 16499, South Korea

Karolina Hanna Prazanowska & Su Bin Lim

Inflamm-Aging Translational Research Center, Ajou University Medical Center, Suwon, 16499, South Korea

Karolina Hanna Prazanowska & Su Bin Lim

Korean Medicine Clinical Trial Center, Korean Medicine Hospital, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, South Korea

Tae-Hun Kim

Department of Acupuncture & Moxibustion, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, South Korea

Jung Won Kang

Korean Medicine Application Center, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daegu, 41062, South Korea

Young-Hee Jin

Korean Medicine Convergence Research Division, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon, 34054, South Korea

Sunoh Kwon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Y.-H.J., S.K. and S.B.L. conceptualized and designed the study. T.-H.K. and J.W.K. were responsible for the clinical part of the study and sample collection. Y.-H.J. and S.K. performed the experiments. K.H.P. analyzed the scRNA-seq data and prepared the original draft. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Correspondence to Young-Hee Jin, Sunoh Kwon or Su Bin Lim.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Prazanowska, K.H., Kim, TH., Kang, J.W. et al. A single-cell RNA sequencing dataset of peripheral blood cells in long COVID patients on herbal therapy. Sci Data 12, 177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04510-1

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04510-1

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

© 2025 Springer Nature Limited

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.