2023 Pi Price Forecast: Is Purchasing Pi Coin Safe? Analytics Insight

source

2023 Pi Price Forecast: Is Purchasing Pi Coin Safe? Analytics Insight

source

At its best, the Internet is a place where community is built and where community is preserved.

One of the most important arenas where the latter occurs is a nonprofit called The Internet Archive. Founded in 1996, Internet Archive is an online library that describes itself as “a nonprofit fighting for universal access to quality information.”

Internet Archive preserves millions of books, radio dramas, concert videos, audio interviews, and more. In addition to this, one of Internet Archive’s most ambitious and most valuable endeavors is The Wayback Machine, which digitally preserves webpages at a particular moment in time. Through the Wayback Machine, we have access to historical views of websites, blog posts, tweets, etc. that would otherwise be lost to hacker attacks, self-deletion, domain lapses, or simply gradual updates.

The Wayback Machine claims to have preserved more than 916 billion such webpages. (Ever want a fun nostalgia trip? Get on the Wayback Machine and type in a URL that you frequently visited 15 years ago. For me, it’s www.lego.com.)

A coalition of major record labels is suing Internet Archive for an obscene amount of money over IA’s “Great 78s” project, an effort to preserve historical recordings made on 78rpm shellac records.

If they succeed, there is a good chance that The Internet Archive and all that it has meticulously preserved will cease to exist.

The article you’re reading now is a call to action.

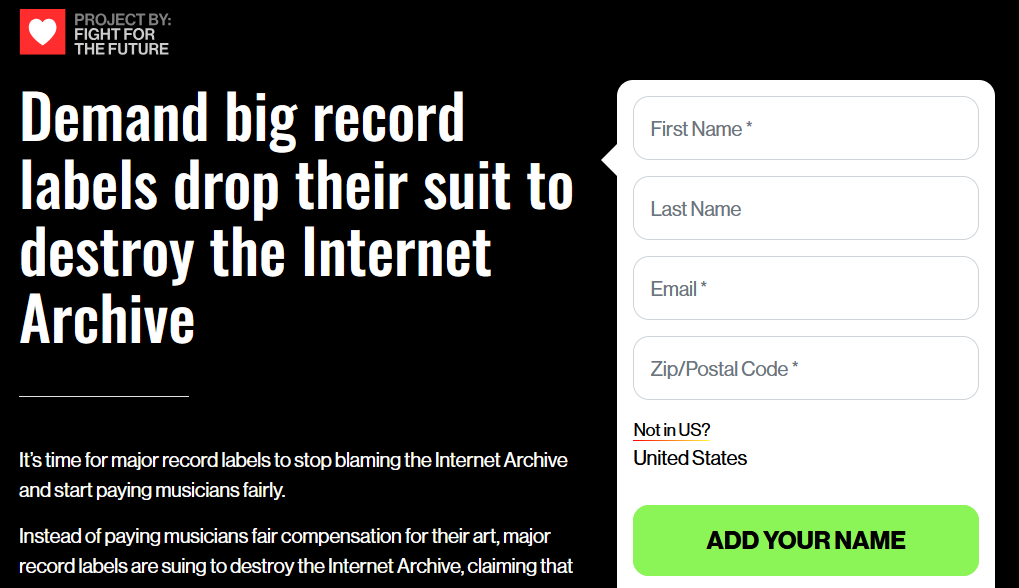

Fight for the Future has put together a petition that hundreds of musicians have already signed. You can sign it today.

Much of our shared cultural history from recent decades has occurred online, and The Internet Archive is the most thorough record of that history. Not to mention the countless pre-Internet documents digitized for the first time through IA’s work.

Here are a few example anecdotes:

“Instead of paying musicians fair compensation for their art, major record labels are suing to destroy the Internet Archive, claiming that their research library of old music recordings is what’s really hurting musicians,” says the petition introduction. “We all know this just isn’t true.” (The petition is very much worth reading in full.)

One of the most valuable attributes of digital media is the ability to preserve large amounts of information from our shared cultural history in a way that is easily accessible to many many users.

Sign the petition demanding big record labels drop their suit to destroy the Internet Archive today by clicking here.

Thanks for reading.

*Note: This article originally appeared in Midnight Donuts.

Christian Rap & Culture’s most visited destination has been Rapzilla.com, since 2003. The top source for new Christian Hip Hop music, news & more. With over 23,000 articles over the last 20 years, Rapzilla is happy to help tell the story of Christian Hip-Hop! Founded by Philip Rood, now owned by Chad Horton, and run by Justin Sarachik, 2023 was one of our biggest yet.

Submissions: https://rapzilla.com/submit/

Copyright © 2024 Rapzilla.com | All Rights Reserved

© THE INTERCEPT

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Indiana wanted to kill Joseph Corcoran under the cover of darkness, but one journalist slipped in to witness.

On the night executioners killed Joseph Corcoran, a glowing inflatable snowman stood on the front lawn of the Indiana State Prison wearing a top hat and frozen smile. Its left arm was raised in a wave, as if to greet the white vans waiting to take witnesses to the death chamber. Inside the brick building in front of the prison complex, shadowy figures stood at the windows, their movements inscrutable from the outside. As the clock struck midnight on December 18, a few dozen protesters sang “Amazing Grace.”

The 165-year-old penitentiary is located in the northern reaches of the state, just half a mile from Lake Michigan. In heavy coats and winter hats, the demonstrators had gathered across the street, braving the cold to stand in protest of Indiana’s first execution in 15 years. They were joined by a handful of reporters, who paced around the parking lot where yellow caution tape cordoned off a “staging area” for press. Under state law and the policies of the Indiana Department of Correction, this was as close as any journalist would be able to get to the execution.

No one knew when exactly the killing would happen, only that it would be carried out “before sunrise.”

“No media briefings or interviews will be conducted,” said informational materials emailed in advance. Nor would there be bathrooms available. “Please plan accordingly.”

In most death penalty states, executions are scheduled to take place in the evening, with at least a few members of the press serving as witnesses. But Indiana planned to kill Corcoran in the dead of night, without a single journalist present. The rule is a relic of the late 1800s, when numerous states carried out executions hidden from public view. Aside from Indiana, only Wyoming, which has not killed anyone since 1992, still has a law barring media witnesses on the books.

George Hale, a reporter with Indiana Public Media, was interviewed in the parking lot by abolitionist group Death Penalty Action. One of the few journalists who repeatedly witnessed the federal executions under Donald Trump, Hale knows better than most that media witnesses are critical for documenting evidence of botched executions. Indiana planned to kill Corcoran with the same sedative used by the federal government: a single lethal dose of pentobarbital, which has been linked to pulmonary edema, the filling of the lungs with fluid. Experts have described the experience as torture.

In an op-ed co-authored with a Freedom of the Press Foundation lawyer, Hale wrote that he’d worked with an anesthesiologist to develop a guide for media witnesses — a checklist of signs that an execution was going awry. Instead, the media ban would hide any red flags.

Hale and other reporters tried to raise alarms about the state’s lack of transparency. As in other death penalty states, Indiana had passed a law shrouding its execution drugs in secrecy. Since obtaining the drugs it would use to kill Corcoran, the Department of Correction had “denied virtually every information request related to the execution,” wrote a veteran journalist with the Indiana Capital Chronicle. “Agency staffers won’t say how many vials were bought, what it cost, the expiration date. Nothing.”

The Department of Correction disclosed only one new piece of information in the hours leading up to the execution, shared in a brief email at 4:45 p.m. Corcoran, it read, “requested Ben and Jerry’s ice cream for his last meal.”

At 12:21 a.m., a stream of uniformed officers exited the prison grounds and headed to a cluster of police cars in the back of the parking lot. It seemed too soon for the execution to be over, but the crowd knew better than to ask them questions. “Merry Christmas,” one officer said to a police colleague as he left.

More than 30 minutes later, at 12:59, the Department of Correction sent an email to the press.

“The execution process started shortly after 12:00 a.m. CST on December 18, 2024,” it read. “Corcoran was pronounced dead at 12:44 a.m.”

“His last words were: ‘Not really. Let’s get this over with.’”

The return of executions in the Hoosier state came largely at the behest of Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, a MAGA stalwart perhaps best known for targeting a doctor who gave abortion care to a 10-year-old rape survivor. In a joint press release with the governor announcing the decision to seek an execution date for Corcoran earlier this year, Rokita called the death penalty “a means of providing justice for victims of society’s most heinous crimes.”

Corcoran was 22 years old when he shot and killed his brother, James, and three other men, including his sister’s fiancé. It was 1997, and the family was still reeling from the murder of Corcoran’s parents five years earlier, a crime for which he was tried as a juvenile and acquitted. News reports said that Corcoran had committed the murders after he overheard the men talking about him. He immediately turned himself in.

Although there was no question of his guilt, there was reason to believe that Corcoran was not competent to stand trial. In the years after he was sentenced to die, multiple doctors diagnosed Corcoran with paranoid schizophrenia. Experts testified at a 2003 hearing that he believed prison guards were using an ultrasound machine to force him to speak. It was this delusion that appeared to have led Corcoran to refuse a plea deal before his 1999 trial; court records show that he would only agree to one if he could first have his vocal cords severed “because his involuntary speech allowed others to know his innermost thoughts.”

Corcoran repeatedly sought to drop his appeals and volunteer for execution. Post-conviction attorneys argued that Corcoran’s severe mental illness made him incompetent to make such a decision, while the attorney general’s office insisted he was fine. In court filings, prosecutors cited a letter in which Corcoran claimed to have “fabricated” his delusions.

After the state announced its plans to kill Corcoran, one surviving relative of his victims spoke out loudly about her opposition to the execution. In a Facebook post in early December, Corcoran’s sister, Kelly Ernst, wrote that his death sentence had done nothing to assuage her grief or bring closure.

“Instead, it is a lengthy, costly and political process,” she wrote. In the years since the crime, her brother had written to express his remorse and she had forgiven him: “I will not attend his execution, neither as family or as victim, as I believe it would take a piece of me that I will not get back.”

As the execution drew near, the prosecutor who sent Corcoran to death row also came out against it. As the elected district attorney of Allen County, where the murders took place, Robert Gevers had urged jurors to send Corcoran to death row, calling it the only proper punishment for such “carnage.” But his feelings about the death penalty had evolved since then. “Times have changed, my own thinking has changed,” he told the Indiana Capital Chronicle.

In a phone call two days before Corcoran’s execution, Gevers said he had come to oppose executions in part due to a conversation with his young son. After the U.S. government killed Osama bin Laden in 2011, his son, then 10 years old, asked him a series of moral questions about the death penalty, unaware that Gevers had once sent someone to die. As he struggled to answer, he began to realize his own stance was untenable.

Gevers later reflected on it in an unpublished essay, which included a scene from Corcoran’s sentencing trial he had never forgotten. The mother of one of the victims had taken the stand. “As she spoke about the loss of her son, the looming years of tragic memories, the future of emptiness in her family, and the awful task of burying a child, she opened the box and set a book on the table in front of her son’s killer,” he wrote. The book was a Bible inscribed with Corcoran’s name. The woman told Corcoran that she forgave him. To Gevers, it was a powerful act of grace. The death penalty was nothing but retribution, he concluded.

Gevers learned about Corcoran’s execution date from a woman at the attorney general’s office, who called him earlier this year “out of the blue.” The news unsettled him. And he was deeply disturbed to learn the state would not allow media witnesses.

“I thought, ‘You have to be kidding,’” Gevers told me. “If this is what the public has said is a legitimate punishment for certain actions, then the public has the right to know how that’s carried out.”

Among lawyers who once handled death penalty prosecutions, Gevers is not alone in turning against capital punishment. In Indiana, as in many other states, prosecutors are increasingly reluctant to seek the death penalty. And, in part thanks to improved capital defense, it has been a decade since an Indiana jury handed down a new death sentence.

A month before Corcoran’s execution, I met veteran attorney Thomas Vanes at the Lake County Public Defender’s Office, an aging brick building that once housed a hospital. Located in the northwest corner of the state, just an hour from Chicago, Lake County once led Indiana in new death sentences, placing more than 20 people on death row between 1978 and 1990, the majority of them Black or Latino. Yet almost none had been executed.

Vanes handed me a packet containing facts and figures about the state’s death penalty record as a whole. Prosecutors frequently invoke executions as providing finality and closure for victims’ families. By this measure, Indiana’s track record was abysmal: Of 97 people sentenced to die after the state passed its modern death penalty law in 1977, the vast majority had not withstood legal challenges. Only 20 had resulted in an execution. As of 2019, 60 people had been removed from death row due to reversals by appellate courts, commutations, or deals reached with the state.

Vanes’s own early career provided a vivid snapshot of this history. As a prosecutor in the Lake County district attorney’s office during the 1970s and 1980s, he sent nine men to the state’s death row.

“Of the nine, only one ended up being executed here in Indiana,” Vanes told me. “And he was a volunteer.”

Two others were executed in other states for different crimes. Of the remaining six, one man took his own life. The rest saw their sentences reduced.

To Vanes, such numbers are an indictment of the whole system — especially considering the tremendous amount of taxpayer money devoted to seeking and defending death sentences. “If you were a cold-blooded economic adviser, you would say that’s a poor return on investment,” he said.

It’s not hard to see why so many of Indiana’s old death penalty cases have failed appellate review. The earliest death sentences were the product of a system that had not created a legal infrastructure to provide meaningful representation to defendants on trial for their lives. As a prosecutor, Vanes said, he had a clear advantage over his opposing counsel.

“The defense was handled by people who were part-time public defenders with their own private practice,” he said. “Meanwhile my workload shrank to afford me the time to do the death penalty cases.” In retrospect, he said, his court victories were nothing to brag about.

Vanes was just two years out of law school when he prosecuted his first death penalty case. It was 1978, and the state had just overhauled its entire criminal code. As Vanes recalls, neither he nor his own bosses were especially well-equipped to apply the new death penalty law. “We didn’t know what we were doing, to be honest.”

Vanes won the case. When it came time for the sentencing phase, even the judge “didn’t quite know what to do, because it was all new,” he said. The defendant, a Black man named James Brewer, became the first person sentenced to die in Indiana’s “modern” death penalty era.

The early victory was a significant career boost for the 27-year-old. Seeking the death penalty became part of the office culture in ways that sound disturbing in retrospect. Vanes remembered the case of a 16-year-old white boy who killed a bank teller during a robbery in 1988. Since the office had recently won a death sentence against a 16-year-old Black girl, Vanes said it felt necessary to try again.

“We pursued it against her,” he thought. “How could we not pursue it against him?”

The jury voted to spare the teenager’s life; today, the Eighth Amendment forbids the death penalty for juveniles.

Brewer’s death sentence was ultimately overturned after a Lake County judge concluded that his lawyer had provided ineffective assistance of counsel. By then, Vanes had left the prosecutor’s office and become a public defender.

“There is always a danger that prosecutors treat their former cases like they were their own children: Protect it at all costs,” he said. By the time his old cases fell apart, it didn’t bother him that much. He did regret the impact on victims’ families who were misled by the death penalty’s false promise of closure.

Vanes articulated an uncomfortable fact that had loomed over Corcoran’s case regardless of the legal arguments over his competency. Sometimes the very evidence that was supposed to spare someone from execution instead convinces people they will always pose a danger, even behind prison walls, he said. “Unfortunately for this man, his mental illness scares people.”

The protesters had mostly disbanded when a trio of prison staff walked toward the parking lot at 1:06 a.m. A man in khakis and a black balaclava clutched a stack of papers, followed by a woman in a fur-lined hood. Behind them, an officer shot a thumbs up at the cops stationed in front of the parking lot.

The man in the balaclava stuffed the papers in an inconspicuous box attached to a No Parking sign. With a teal marker, someone had written “Media Statement” in clumsy block letters. The papers were one-page press statements — printed versions of the email sent out moments before — never mind that there was virtually no one left to receive them. The officials walked back to the prison in silence.

Shortly afterward, news broke that a local journalist had managed to attend the execution after all. Reporter Casey Smith from the Indiana Capital Chronicle had gotten on Corcoran’s personal witness list. Her dispatch, published around 3 a.m., filled in key gaps in the state’s narrative.

Official language stated the “execution process” had begun shortly after midnight, raising concerns that the lethal injection had dragged out for more than 40 minutes. But Smith’s article revealed that the execution had gone relatively quickly.

“Blinds for a one-way window with limited visibility into the execution chamber were raised at 12:34 a.m.,” she wrote. “Corcoran appeared awake with his eyes blinking, but otherwise still and silent, at that time. After a brief movement of his left hand and fingers at about 12:37 a.m., Corcoran did not move again. Blinds to the witness room were closed by the prison warden at 12:40 a.m.”

It was not clear what happened in the four minutes between the closing of the blinds and the estimated time of death. Nor is it known what was said in the execution chamber apart from the words prison officials chose to share. Generally speaking, however, the execution appeared to have gone according to plan.

A spiritual adviser who accompanied Corcoran as he died described the final visit in an interview with Smith. “We had prayer together,” he told her. “We talked and laughed, we reminisced.” He said Corcoran seemed less concerned about himself than his neighbors.

“He actually was talking more about the other guys on death row, and how it was going to impact them. He wasn’t talking about his own feelings and fears,” the spiritual adviser told Smith. “From my perspective, it was very, very peaceful.”

WAIT! BEFORE YOU GO on about your day, ask yourself: How likely is it that the story you just read would have been produced by a different news outlet if The Intercept hadn’t done it?

Consider what the world of media would look like without The Intercept. Who would hold party elites accountable to the values they proclaim to have? How many covert wars, miscarriages of justice, and dystopian technologies would remain hidden if our reporters weren’t on the beat?

The kind of reporting we do is essential to democracy, but it is not easy, cheap, or profitable. The Intercept is an independent nonprofit news outlet. We don’t have ads, so we depend on our members to help us hold the powerful to account. Joining is simple and doesn’t need to cost a lot: You can become a sustaining member for as little as $3 or $5 a month. That’s all it takes to support the journalism you rely on.

Protests for Black Lives

Chris Gelardi

A newly obtained document sheds light on how the disavowed “excited delirium” diagnosis infiltrated the Rochester Police Department before Prude’s death.

Israel’s War on Gaza

Sanya Mansoor

“I have a fundamental right to be protected by my government, especially in times of war. My children and I deserve to return to the safety of the U.S.”

The Intercept Briefing

The Intercept Briefing

Biden is running out of time to stop another Trump execution spree.

© The Intercept. All rights reserved

This is not a paywall.

By signing up, I agree to receive emails from The Intercept and to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Independent journalism is facing unprecedented attacks, but we’ve never been afraid of making powerful enemies.

The Intercept needs to meet this year-end fundraising goal to keep going strong.

Security cabinet holds meeting in north The Times of Israel

source

In the rapidly evolving world of cryptocurrency, a new name has emerged, sparking curiosity and excitement among enthusiasts and experts alike: Hawk Tuah Girl. Known for her enigmatic online persona, Hawk Tuah Girl has taken the crypto community by storm with her innovative approach to decentralized finance.

Drawing inspiration from both traditional financial systems and cutting-edge blockchain technology, Hawk Tuah Girl is pioneering new ways to enhance security and accessibility in the crypto sphere. Her latest project, tentatively named “Tuah’s Vault”, aims to provide a user-friendly platform that merges complex algorithms with intuitive design, making crypto investments accessible to a broader audience.

The core of Tuah’s Vault lies in its unique ability to automate the protection of digital assets using a smart contract-based insurance mechanism. This feature not only ensures robust security but also empowers users to take control of their financial destiny, mitigating risks commonly associated with cryptocurrency investments.

The buzz surrounding Hawk Tuah Girl is not just about her technological prowess; it’s also about her commitment to community engagement and education. She regularly hosts online seminars and workshops, demystifying the intricate world of crypto for newcomers and seasoned investors alike.

As the crypto landscape continues to evolve, Hawk Tuah Girl’s forward-thinking approach and her emphasis on inclusion and education position her as a trailblazer in the industry. Whether her initiatives will reshape the world of digital currencies remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: Hawk Tuah Girl is a name to watch.

In the rapidly evolving landscape of cryptocurrency, one innovative figure has become the focal point of intrigue: Hawk Tuah Girl. Recognized for her enigmatic digital presence and forward-thinking contributions to decentralized finance (DeFi), Hawk Tuah Girl is at the forefront of transforming the accessibility and security of digital financial ecosystems.

Emerging Trends and Innovations

Hawk Tuah Girl has introduced new concepts in DeFi through her latest project, “Tuah’s Vault.” This platform is breaking barriers by integrating complex blockchain algorithms with easy-to-understand interfaces, thereby attracting both novice and expert investors. In an industry often criticized for its complexity and exclusivity, this project offers a breath of fresh air with its emphasis on user-friendly design.

Key Features of Tuah’s Vault

The standout feature of Tuah’s Vault is its smart contract-based insurance mechanism. This innovation ensures a high level of security for digital assets, providing peace of mind for users concerned about the notorious volatility and risks of cryptocurrency investments. By automating asset protection, Tuah’s Vault empowers users to manage their financial futures more intuitively and securely.

Community Engagement and Education

Beyond technological advancements, Hawk Tuah Girl distinguishes herself with a commitment to fostering community engagement and education. Understanding the importance of knowledge dissemination in the cryptocurrency space, she regularly conducts online seminars and interactive workshops. These sessions are designed to demystify the often perplexing world of crypto, making it more accessible to a wider audience. Her efforts contribute to building an informed community capable of navigating the complexities of digital finance confidently.

Challenges and Opportunities

While Hawk Tuah Girl’s initiatives are groundbreaking, they come with challenges. The ever-changing nature of digital finance poses questions about regulatory compliance and long-term sustainability. However, her proactive stance on educating the community and enhancing inclusivity addresses these concerns. As more participants enter the crypto market, initiatives like Tuah’s Vault could play a significant role in shaping a more secure and inclusive financial landscape.

Future Predictions and Market Impact

With cryptocurrency’s continued integration into mainstream financial systems, projects like Tuah’s Vault are well-positioned to capitalize on emerging trends. Hawk Tuah Girl’s dedication to security and accessibility aligns with broader market demands, suggesting a promising future for her initiatives. Her work not only captivates the crypto community but also positions her as a key influencer in the industry’s evolution.

For more insights into the dynamic world of cryptocurrency and decentralized finance, explore Blockchain. As Hawk Tuah Girl’s contributions continue to unfold, her vision could redefine the contours of digital currency management, making her a noteworthy pioneer to follow in this digital age.

Avah Woulfe is a distinguished author and thought leader specializing in new technologies and fintech. With a degree in Information Systems from the University of Georgia, Avah brings a strong educational foundation to her writing. Her experience includes a significant role at FinConnect, a leading financial technology consultancy, where she honed her expertise in innovative solutions that bridge the gap between finance and technology. Avah’s insightful analyses and forward-thinking perspectives have established her as a trusted voice in the industry. Through her articles and research, she empowers readers to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of fintech, making complex topics accessible and engaging.

Your email address will not be published.

Could JasmyCoin Be the Next Big Thing? Discover the Future of Decentralized IoT

The Pico W has WiFi and getting started is easier than you might think from the documentation. But how do you get connected? This isn’t a matter of only connect – there is more to do! This is an extract from our latest book all about the Pico/W in C.

Buy from Amazon.

Extra: Adding WiFi To The Pico 2

<ASIN:1871962803>

<ASIN:187196279X>

The Pico and the Pico W are very similar and, with the exception of anything that uses the built-in LED, all of the programs presented so far work on both models. The important difference between them is that the Pico W has additional hardware that enables it to use WiFi. From the programming point of view, however, the task is to learn how to use the new WiFi driver and the LwIP library that provides higher-level networking. This is made more difficult than need be by the inadequate documentation provided for both. This will probably improve over time.

The Pico W has additional libraries to make it possible to work with the WiFi hardware without having to work at the level of the SPI interface. You can think of these libraries as forming a set of levels. The lowest level is the cyw43_driver which provides an interface to the hardware via the SPI interface. In most cases you can ignore the functions in this module apart from the ones concerned with scanning for access points and power management.

The pico_cyw43_arch library provides higher-level functions mostly concerned with setting up the WiFi and making connections. This is documented and is a good place to start.

The pico_lwip is a set of wrapper functions around the LwIP open source IP stack. This has been ported to the Pico and works with IP via the WiFi drivers. There is almost no documentation of pico_lwip but the original LwIP project is fully, if not particularly clearly, documented.

The WiFi hardware needs periodic attention and when used with an operating system this is usually taken care of by multithreading, but the Pico doesn’t have an operating system unless you install one. The pico_cyw43_arch library provides three different ways of achieving the regular attention that the hardware needs. The first relies on polling, the second uses interrupts and the third makes use of the threads provided by the FreeRTOS operating system.

The mode used depends on which library you link to in CMakeLists.txt. There are three choices, the first being pico_cyw43_arch_lwip_poll. Using this library the client program has to call cyw43_arch_poll() every so often to allow it to run the WiFi software so that it can call callbacks and generally move data. This is a very simple arrangement as it is entirely synchronous and there is no danger of a race condition and hence no need for locking of any kind. It has the disadvantage that it is not multi-core nor interrupt-safe. That is, if you are running code on the second core or if you are making use of interrupts, the networking code can be interrupted in ways that corrupt data.

The second choice is, pico_cyw43_arch_lwip_threadsafe_background. In this case there is nothing the client program has to do and the driver and LwIP code is called by an interrupt. This is multi-core and interrupt-safe, but only if you use locking when you call LwIP code. All callbacks are called in interrupt mode. Any code not run by LwIP has to be bracketed by the instructions cyw43_arch_lwip_begin and cyw43_arch_lwip_end. These apply locks which stop interrupts and other cores running the code at the same time. You don’t have to bracket calls to LwIP made within callbacks because these are being run by LwIP, but if you do they have no effect.

While you can use the threadsafe_background mode with freeRTOS, the preferred mode is to use it with pico_cyw43_arch_lwip_sys_freertos, the third library. The freeRTOS operating system adds the ability to run multiple tasks at different levels of priority – it provides a basic “threads” capability. This allows the LwIP software to run independently and in an organized way with your custom code. The installation and use of freeRTOS is a big undertaking and in most cases it is best avoided for simple WiFi applications.

The freeRTOS approach to WiFi is best taken if you want to use freeRTOS to structure your entire application. In the rest of this chapter the examples will use the threadsafe_background mode, but it is easy to convert them to polling mode by adding calls to cyw43_arch_poll(). It is important to notice that you can only use LwIP sockets if you are also using freeRTOS. Without freeRTOS you are limited to the “raw” LwIP APIs.

There is also a mode, set by using the pico_cyw43_arch_none library, which disables WiFi but allows access to the onboard LED. This is what was used in Chapter 2 to flash the onboard LED.

Texas lawmakers should reject cruel effort to decriminalize animal fighting San Antonio Express-News

source

NEW YORK (WABC) — A massive prize currently estimated at $944 million ($429.4 million cash) is on tap for the next drawing on Christmas Eve.

The jackpot rolled again after no ticket matched all six numbers drawn Friday night – the white balls 2, 20, 51, 56 and 67, plus the gold Mega Ball 19.

If won at that level, it would be the largest prize ever won in December and the seventh largest in Mega Millions history!

Thirteen Mega Millions jackpots have been won during December since the game began in 2002. Three were won in the days after Christmas, while the other 10 were won before Christmas. There has never been a jackpot win on Christmas Day, although over the years drawings have been conducted on Christmas six times – in 2007, 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2020.

The Mega Millions jackpot was last won at $810 million in Texas on September 10.

Before that September 10 prize in the Lone Star State, the Mega Millions jackpot was won only twice earlier this year. A $552 million windfall was awarded to an Illinois online player on June 4, and a whopping $1.128 billion prize still awaits a ticket-holder in New Jersey; no one has yet come forward to claim that jackpot from March 26. If not claimed, this ticket will expire on March 26, 2025, and the unpaid prize will revert back to each participating Mega Millions jurisdiction.

The odds of winning the jackpot are 1 in 302,575,350, according to Mega Millions.

Mega Millions is played in 45 states, Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Tickets are $2 for one play.

1. $1.602 billion, August 8, 2023 (one ticket in Florida)

2. $1.537 billion, October 23, 2018 (one ticket in South Carolina)

3. $1.348 billion, January 13, 2023 (one ticket in Maine)

4. $1.337 billion, July 29, 2022 (one ticket in Illinois)

5. $1.128 billion, March 26, 2024 (one ticket in New Jersey)

6. $1.050 billion, January 22, 2021 (one ticket in Michigan)

7. $800 million, September 10, 2024 (one ticket in Texas)

8. $656 million, March 30, 2012, (three tickets in Illinois, Kansas, Maryland)

9. $648 million, December 17, 2013 (two tickets sold in California, Georgia)

10. $552 million, June 4, 2024 (one ticket in Illinois)

1. $2.040 billion, Powerball, Nov. 7, 2022 (one ticket: California)

2. $1.765 billion, Powerball, Oct. 11, 2023 (one ticket: California)

3. $1.602 billion, Mega Millions, Aug. 8, 2023 (one ticket: Florida)

4. $1.586 billion, Powerball, Jan. 13, 2016 (three tickets: California, Florida and Tennessee)

5. $1.537 billion, Mega Millions, Oct. 23, 2018 (one ticket: South Carolina)

6. $1.348 billion, Mega Millions, Jan. 13, 2023 (one ticket: Maine)

7. $1.337 billion, Mega Millions, July 29, 2022 (one ticket: Illinois)

8. $1.128 billion, March 26, 2024 (one ticket in New Jersey)

9. $1.08 billion, Powerball, July, 19, 2023 (one ticket: California)

10. $1.05 billion, Mega Millions, Jan. 22, 2021 (one ticket: Michigan)

WATCH: New York state lottery drawings live daily at 2:30 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. and Wednesdays and Saturdays at 8:15 p.m.

Powerball drawings are also streamed here on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday at 10:59 p.m.

Mega Millions drawings are streamed on Tuesday and Friday at 11:00 p.m.

Sources: AP archives, www.megamillions.com and www.powerball.com

———-

* Get Eyewitness News Delivered

* Follow us on YouTube

* More local news

* Send us a news tip

* Download the abc7NY app for breaking news alerts

Have a breaking news tip or an idea for a story we should cover? Send it to Eyewitness News using the form below. If attaching a video or photo, terms of use apply.