50% off ends tonight! Join Now.

Advancing the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

Ashley Hales

Some young Christians embrace lower-tech options.

Young adults “do have a desire for an unplugged life,” said Luke Simon, a youth codirector at The Crossing in Colombia, Missouri, as we spoke about his own generation—Gen Z—and Gen Alpha.

“Technology is the way they’re viewing the world,” the 24-year-old said, so much so that choosing lower-tech options or going analog feels like the equivalent of going off grid. It’s an alternative lifestyle.

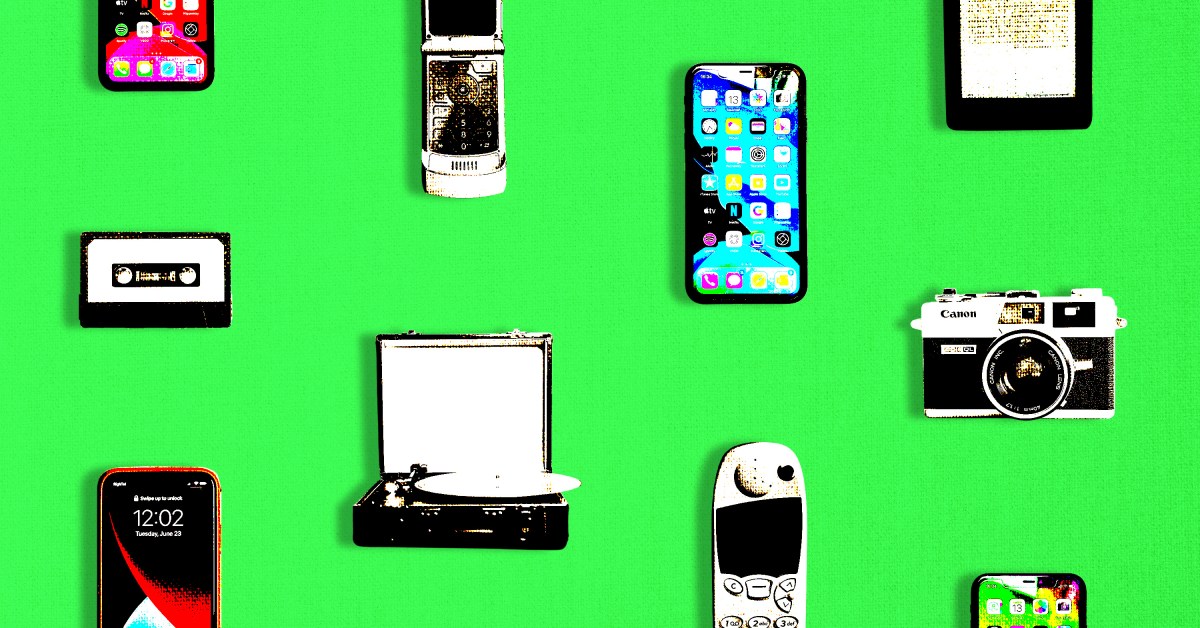

But many young people are making such choices. The Wall Street Journal has reported a surge in flip phones, digital cameras, and CDs, alongside a growing interest in Luddite clubs and collective action groups like Time to Refuse, where Gen Zers collectively delete apps.

It seems everyone is talking about how smartphones have made us less mentally agile, and experts like Jonathan Haidt continue to sound the alarm on their association with poor mental health. But what are digital natives doing about it as they enter adulthood? And for Christians, how do these types of technology choices affect the faith of younger generations?

Get the most recent headlines and stories from Christianity Today delivered to your inbox daily.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for signing up.

Explore more newsletters—don’t forget to start your free 60-day trial of CT to get full access to all articles in every newsletter.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

Molly Stevenson, a benefits advisor in Washington, DC, remembers a time when you could get to the bottom of your social media feed. Today, part of her interest in using film and digital cameras instead of her smartphone is the attention it requires.

On a recent trip to Peru, Stevenson, who is 27, took only a handful of pictures of Machu Picchu, waiting for the light to be just right. “I had the whole day, and only two of them turned out, and that’s okay.” She found that lower-tech options tend to slow down time: When she looks back at the photos days or weeks later, she feels they bring back memories, as opposed to viewing digital photos on her phone immediately after taking them. In her church small group, they talk about social media as a “socially acceptable drug.”

Heather Thompson Day

Russell Moore

Julianna Graeber, a recent graduate of Liberty University living in New Jersey, said using point-and-click cameras produces more aesthetically pleasing photos without as many filters or apps. Playing vinyl records also constrains her options so that “you have to listen to the whole album and not just skip through songs.”

Our attention is not only divided but also dumbed down. Lane Brown, in a New Yorker Magazine article called “A Theory of Dumb,” reported that “recent shifts suggest we’ve crossed a kind of threshold. In June, the Reuters Institute noted how social media is now Americans’ main source of news, surpassing legacy outlets for the first time. Worldwide, TikTok is a trusted news source for 17 percent of people.

This shorter attention span has consequences for how we understand vocation. Graeber, who is 22, found her attention had evaporated so that she could no longer read fiction like she used to. It provided a reckoning as a writing major: “If I believe that I’m serving God and my purpose is to give back to him with those gifts, I am responsible for my attention span to be able to read and write.” A school-sponsored monthlong digital fast allowed her to see her tech overuse not just as a bad habit but as tied to her vocation and love of God.

Ciara McLaren, an American Christian living in London (who also writes on analog life), started a Lenten fast by putting her iPhone in a drawer and choosing a Nokia 2780 phone instead. While the 28-year-old has missed out on some things (she didn’t get the instantaneous news of her sister’s engagement, for example), she said, “It just makes me more determined to build a life closer to the people I love, and to visit in person as much as possible.” The space for clear thinking and prayer make up for the desire to always be connected.

While not eschewing all technology, many Gen Zers are showing an interest in choosing more humane forms. Rather than bowing to the need to feel constantly connected, these subtle shifts—to vinyl records, point-and-shoot cameras, and WiFi-only e-readers—are a way to reclaim attention.

Covenant College chaplain Grant Lowe shared how some students are opting for dumbphones like the Light Phone and Wisephone. Some use Brick, which markets itself as a “digital wellness tool that blocks distractions and makes your phone a tool again,” he said. “Some students are downloading Google extensions that allow users to customize their YouTube pages, removing reels and all suggestions, freeing them from all-too-effective targeted algorithms.”

These lower-tech choices allow for a renewed focus on God and others. Twelve years ago, when Lowe banned cell phones from Covenant’s thrice-weekly chapel services, he was prepared for pushback. “Instead,” he said, “it was met with a standing ovation that I’ve always believed was a communal sigh of relief—to have a place they can together be free from technological distraction, if only for 35 minutes.”

Natalie Mead

Russell Moore

Cutting down on distractions and screen time also seems to have mental health benefits. Graeber commented she was “making herself sick” by being constantly plugged in. Largely eliminating social media “brought my anxiety levels down significantly.”

Another Gen Z creative, Sophie Jouvenaar, noted the challenges of early phone adoption: At “11 years old, I got a phone, which almost immediately opened the door to predators and cyberbullying from my school peers. As a result, I really struggled.”

The online environment also opened up opportunities for a photography career at 17. Still, at 22, she had to take a break from her work because social media deteriorated her mental health. She moved back in with family and learned to speak with God and read his Word.

Now 24, Jouvenaar has realized not only her need for slower forms of technology but also for Christ. Her photography is a testament to her lower-tech commitments, and she finds clients “through real-world interactions, word of mouth, emails, even posters and business cards.”

“The benefits of these ‘lower tech’ alternatives allow me to really consider how I work and who I want to work with,” she said, “rather than swimming in the mad panic of posts, DMs, and likes.”

One consideration for those who are considering lower-tech options is the desire to stay relevant in the job market. Daniel Coats, a marketing communications coordinator at Cal State Fullerton, thinks it’s possible to stand out in a crowded marketplace without embracing every tech advancement.

Ashley Hales

Ashley Hales and Jared Boggess

Coats was a late tech-adopter, yet he has found that he’s “strong as a social media writer because the mechanics of writing don’t really change and you can adapt to the mediums as they come up.” While he’s curious about the implications of AI for his job, he’s also confident that the skills he uses at work and in his local church will remain relevant.

Most of the Gen Zers I spoke with discussed tech usage or digital fasts with their friends, but it didn’t seem to be a primary component of discipleship in their churches. Sometimes it was only acknowledged as a common problem or, at times, as a specialized area of study.

Patrick Miller, a pastor at The Crossing, mentioned that as awareness of the shaping power of technology grows, there’s “a much higher willingness to engage with disruptive practices designed to recapture [Christians’] love of God over their love of the machine.”

Miller has seen practices like a digital fast or setting your phone to grayscale to be effective. He has limited his own social media usage, noting that “the incentive structures of social media are almost antithetical to a local pastor’s calling. What does well on social media is what is invective and angry and shocking. And that is the opposite of what a pastor should be.”

Joshua Heavin of Christ Church Plano in Texas also noticed how his offline habits were shaped by his online smartphone usage. As curate for pastoral care, he said the smartphone takes away from a “disposition of hospitality” and “erodes his capacity for such a way of life.”

Our digital addiction may be a revolt against the reality that “we are finite, and often frustrated with the particular place, people, and situations that have been given to us, and that in the end that we are not self-made,” noted Heavin.

“We spend an enormous amount of time imagining ourselves in the past with regret or nostalgia, or in the future with anxiety and fear, but we are very rarely present in the one place where God comes to us by his Word in Spirit: in the present,” Heavin said. “But if we can receive it, we will perceive that our particularity is a gift, and the particularity of Jesus Christ is the mystery through which the whole cosmos is renewed.”

Gen Z’s analog attempts may help us begin to recover not only the reality but also the pleasures associated with our finitude. We need to do so together, across generations, Heavin says: “It is much more realistic and doable to live such a life in a community who shares that common goal than to attempt it all alone.”

Ashley Hales is CT’s editorial director of features. She serves on the board of Covenant College.

Maaike E. Harmsen

Jeffrey Bilbro

Russell Moore

Jeremy Writebol

View All

CT Editors

Our picks for the books most likely to shape evangelical life, thought, and culture.

Marvin Olasky

20 more suggestions from our editor in chief.

The Bulletin

Steve Cuss, Clarissa Moll, Russell Moore

Hosts of CT Media podcasts discuss their Christmas traditions, memories, and advice for navigating the season.

Review

Grace Hamman

Classicist Nadya Williams argues for believers reading the Greco-Roman classics.

Ashley Hales

Some young Christians embrace lower-tech options.

Being Human

How your nervous system helps you notice God

Dorothy Littell Greco

When we fail to protect and honor women like Jesus, we all lose.

Chris Poblete

When we outsource intimacy to machines, we become what we practice. And we’re practicing the wrong things.

You can help Christianity Today uplift what is good, overcome what is evil, and heal what is broken by elevating the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

© 2025 Christianity Today – a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International. All rights reserved.

Seek the Kingdom.